"0% detection has never felt better"

Exploring some of the risks to students from the adoption of generative AI in HE

A little while ago I promised three posts on the risks of generative AI use in higher education. I was just about to press ‘publish’ on this one, about risks to students, when my friend and colleague Sheila MacNeill sent me a link to another AI in education framework. This one is for use in Australian schools.

Credit to the Ministry of Education in Australia for producing such a comprehensive list. The framework has six core elements, each inspiring several ‘principles’, and each of the 22 principles can be reverse engineered to show the risk that the writers of this document (presumably) had in mind. The heuristic is a simple one:

[There is a risk that] generative AI tools [will fail to] expose users to diverse ideas and perspectives, [and will reinforce] existing biases.

[There is a risk that] the use of generative AI [will fail to] respect human rights and safeguard the autonomy of individuals, especially children.

It’s been useful to check my own thinking about risk against the work of the Ministry, but I’m also puzzled by the way the document is framed. (It is only a consultation document at this stage, so more guidance may be on its way). It would be difficult to assess whether any use complied with these principles without a lot more knowledge of the underlying platforms than is publicly available. Lack of transparency, inherent bias, violation of human rights, exploitation of cultural and intellectual goods, harm to knowledge communities… observers of GenAI inside and outside the temple have been trying to evaluate the extent of these risks, and often failing. As I argued in my post on the false equivalence between opportunity and risk, it is hard to assess in advance the consequences of linking a new technical architecture to the knowledge systems and labour platforms used by billions of people.

As an educator, I’d want to know that the underlying architectures meet these principles. So if I can use them ‘in accordance with their intended purposes’ I can hope to be fair, transparent, beneficial and accountable, etc. Absent this assurance, the principles end up saying exactly the opposite of what they (seem to) mean. Because in fact Generative AI tools don’t ‘provide a fair and unbiased evaluation of students’ performance, skills and knowledge’. They don’t ‘expose users to diverse ideas and perspectives’. Even very mainstream commentators say they will always be ‘a threat to diversity, inclusion and equity’. Nobody can agree what ‘applicable copyright rights and obligations are’ in relation to these platforms, but there are class actions all over the place alleging that they have been broken. ‘Human accountability’ is deliberately obscured by GenAI architectures, and legal accountability for harm in use remains untested. And so it goes on.

(In fact, US legal expert Lance Eliot writes in his regular column on AI that OpenAI’s Terms of Use effectively indemnify the company against anything you might do with ChatGPT and its outputs. Not only are you liable for any harms, but if OpenAI is sued as a result of harms arising from your use, you are also liable for their legal costs. I’m not sure Australian schools are ready for this, financially speaking.)

The laudable aim of the Australian AI framework is to encourage everyone involved in education to ‘think carefully about intended and unintended consequences’. Like the Russell Group framework that I wrote about a few weeks back, it names many of the risks, even if it does so in a contrary way. But like that framework, it leaves individuals to assess the specific risks in their own contexts of use, as though every school is its own unique setting, and ‘AI tools’ are themselves entirely neutral in respect of the potential harms.

I don’t feel that any of us is equipped to do these assessments on our own, even with a lot more evidence and advice. But I am going to take up the challenge of thinking carefully about some possible consequences, focusing on consequences for students, and on the duty of care educational institutions have to them.

Accusations of ‘misuse’

One present risk to students is that they may be accused of misusing generative AI in a summative assessment. ‘Misuse’ is a fluid concept here. Regular readers may remember my deconstruction of the guidelines issued by the Association for Computational Linguistics back in the day – that is, a few short months ago. The line between legitimate use and ‘misuse’ for ACL depends on how ‘long’ a piece of text is, and how ‘original’ the concepts it deals with. Guidance to students from universities must navigate the same tricky terrain. Unlike the ACL, though, many universities have switched their position completely in the months since GenAI first appeared. Newly invented referencing conventions only add to the potential for confusion. Are the outputs of GenAI a ‘personal communication’ to be referenced, a company (e.g. OpenAI) to be acknowledged, or a process to be described in the method section? I have seen all of these recommended.

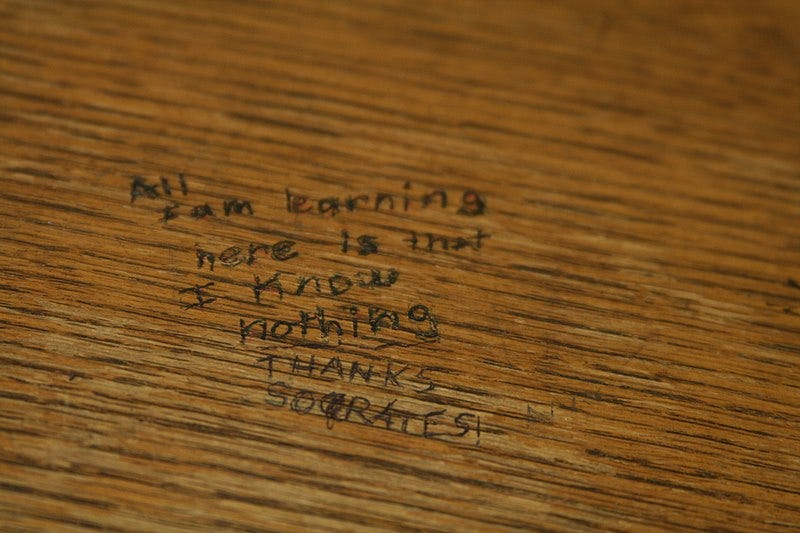

A recent investigation by the Tab student paper found 40% of universities had accused students of using AI to ‘cheat’ and that this was just the tip of the iceberg. Some accusations had been triggered by AI ‘detection’ software, as recorded by Jim Davison of WonkHE in a series of tweets. I think this is a particularly harmful way for students to end up under investigation. A rigorous study by eight international experts exposed:

serious limitations of the state-of-the-art AI-generated text detection tools and their unsuitability for use as evidence of academic misconduct. Our findings do not confirm the claims presented by the systems. They too often present false positives and false negatives. Moreover, it is too easy to game the systems by using paraphrasing tools or machine translation. Therefore, our conclusion is that the systems we tested should not be used in academic settings.

And the authors go further. Reviewing the technical basis for claims to ‘detect’ use of AI, they conclude that ‘the “easy solution” for detection of AI-generated text does not (and maybe even could not) exist’. Meanwhile a credible piece of research by four Stanford students found that ‘detection’ software is systematically biased against non-native speakers and less confident users of academic English. No university using this software can claim to be transparent or fair, even if they have other ways of ‘detecting’ AI ‘misuse’.

Rightly, many UK universities have opted not to use these systems – this statement from the University of Manchester sums up the case. Instead they are asking teachers to specify how synthetic text may and may not be used in each assignment, and to assess the outcomes. This is good for academic autonomy. It is good for conversations with students. Individual teachers and indeed whole courses and departments may begin to shift the balance of assessment towards more authentic and developmental approaches. Lancaster Student Union is one of the student bodies pushing for this outcome:

alternative methods of assessment, such as verbal… more variety of assessment methods and a withdrawal of assessment methods which have become obsolete.

But this case-by-case approach puts a huge burden of responsibility and work on teaching staff, at a time when the profession is on its knees. It also isn’t good for providing clarity and consistency to students in an area where they are extremely vulnerable, and where general university processes will in the end determine what is ‘misuse’.

For example, most universities have drawn a line at students ‘passing off’ synthetic text as their own. This is consistent with existing provisions on academic integrity, and seems like a simple test of honesty. But it is not enforceable. ‘Passing’ is what synthetic text does. That is its entire use case, its function and fascination. Every generated instance is unique, and the terms of use give ownership of that unique text to the user. Are honest students supposed to declare every use they make of GenAI, even if many of those uses are playful or experimental or inconclusive (as we encourage them to be)? Are students supposed to make their generated text less ‘passable’, less ‘grammatically correct’ for example, before submitting it (as these are now red flags for cheating)? Soon it may be difficult even to know how synthetic text has got into the mix. Turn on Copilot in your Microsoft office suite, link Coefficient with Google Sheets as you analyse data, lean on Github Copilot to debug your code, or search with Bing or SGE, and you could be ‘misusing’ GenAI without ever launching a chat interface or writing a single prompt.

Rather more than anyone would like, student behaviour depends on whether they believe that universities have a way of detecting this generated text. A survey in March found US students evenly split on this issue. The furore about Turnitin’s AI ‘detection’ in the UK has made headlines in most student papers, so UK students may be more inclined to doubt. And they would be right to doubt, because there is emerging evidence e.g. here, here and here that teachers are not much better than the software at deciding whether texts are synthetic or written by students. (Disclosure: I’ve supervised masters’ students in a number of settings, where I’ve had a lot more time to attend to their writing than the average undergraduate tutor. I’ve studied and taught writing as a discipline, and I’m familiar with how paraphrasing apps, translation engines, GPT interfaces and grammar checkers work. And I would find it difficult to say exactly how a student had made use of these tools. Sudden changes in fluency and crude cut-and-paste jobs are easy to spot, but the more resources for writing a student already has, the more they can smooth over the joins.)

There are immediate risks, then, to students who are wrongly or unfairly or unequally accused of cheating. There are medium term risks of widening inequality, and of leaning too heavily on students’ ‘honesty’ about issues that are complex at best. But longer term, surely there is a risk that students may lose faith in the capacity of universities to assess them at all, and in the value of their qualifications once they have graduated.

Why am I even here?

Because even if students never get challenged over their use of synthetic text, they have concerns. That US survey back in March found that 40% of students believed ‘the use of AI by students defeats the purposes of education’, and more recent research in Hong Kong (Chan and Hu 2023, paywalled) found students mostly agreed (mean score 3.15 out of 5) that ‘using generative AI technologies such as ChatGPT to complete assignments undermines the value of university education’. Writing on the LSE blog, Utkarsh Leo points out that students have always been sensitive to opportunities (other) students have to cheat, because it devalues their work. What is the value of a university degree – and the work that goes into achieving it – if anyone with a free chatbot can now pass themselves off as a graduate?

Head over to StudentBeans or any student-friendly social media spot and you’ll find students on the one hand complaining they are surrounded by ChatGPT cheats, and on the other hand swapping tips about how to get away with it themselves.

Like Silicon Valley’s most cherished child, GPT-4’s achievements are constantly in the headlines: it can now ‘pass Harvard courses’, ‘pass medical exams’, ‘pass bar exams’ and ‘pass a raft of standardised (US) tests’. Its parents must be so proud. I think it matters what universities say about this. It matters whether GPT-4 and other language models are ‘really’ reasoning about issues in law, medicine and business or producing credible performances of it. (It matters what ‘academic performance’ is.) Can universities offer assurances about the value of learning that hold up in the face of these challenges?

In recent weeks I’ve followed arguments on HackerNews, developer Reddits and GenAI discord channels that have dived deep into questions about intelligence, reasoning and knowledge. It is not to denigrate developers to suggest that the same quality of discussion should be evident in the social media channels of higher education. Educators have at least as much at stake. Educators are supposed to know how to talk about this kind of thing.

To put this problem of the value of learning in a historical perspective, the technologies of online search did bring significant changes in what universities taught and assessed. Library and information skills became more important, academic integrity policies evolved. Ways of thinking were more explicitly valued than ‘knowing stuff’ (it was never the case that ‘knowing stuff’ didn’t involve ‘ways of thinking’, but the discourse became more explicit, for example through the use of Bloom’s taxonomy and discourses of ‘deep’ and ‘surface’ learning). The question ‘why go to university when everything you need to know is on the internet?’ demanded answers, and answers were found. But the process was slow, and it didn’t help that it was often oppositional, with ‘disruptors’ championing new technologies on the one hand and ‘traditionalists’ waving noble purposes and values on the other. I’ve spent my career labouring in this gap, and in my experience academics just want an honest, intelligent dialogue across the middle. Spaces for holding that dialogue are now urgently needed. Because the new challenge is coming up fast, and it is an even more disturbing one than knowledge abundance and the ease of search: ‘Why go to university if a large language model can think like a graduate?’

Relations between teachers and learners

The risks to students’ motivation and sense of self-worth from the public discourse about GPT should be obvious. One choice teachers can make is to design the kind of assignments that I have called ‘accountable’, and that are often described as ‘authentic’, (the link is to a scholarly overview by Jan McArthur, but any search will produce some valuable recent thinking). Here, the value of GenAI is limited by reference to some ‘real world’ beyond language models, and student writing is supported as a process of engagement with that world. It’s a choice that demands a lot of time and commitment, over and above what have become ‘traditional’ assessment methods. But it is one that can reassure learners about the value and relevance of their learning.

The other option is for teachers to say to students: let’s assume that all work can now involve synthetic text, including my own research publications and teaching materials, and the work you will do as a graduate. What does this mean for your degree, for your writing and thinking, for the kind of assessment you think is worthwhile, for the kind of work you hope to accomplish? Some educators are having these conversations with students. But the implications are profound. Is it safe for students to discuss their use of GenAI openly, for example? Is it OK for academic staff as lone actors to declare a truce in the war on academic misconduct? Conversations of this kind should rather, I think, be community-wide, with ground rules to keep everyone safe, and a commitment to hearing minority and outlying voices. Without that kind of organisational support, this second option demands even more time and commitment from teaching staff than the first.

Both options might deepen relationships and trust between teachers and students. But the GenAI challenge comes at a difficult time. Educators are broken: relations between academics and universities are at a historic low point. As I wrote in a companion piece on risks to teachers, GenAI is a productivity tool. It is not designed to deepen relationships but to save time, ‘upscale’, and increase the through-put of students per unit of teaching labour. As resources tighten, the temptation will be strong to keep doing more ‘standard’ assessments, or even to ramp up standardisation because standard assessments can be proctored by AI, and now GenAI tools can take over the grading as well. And while it will surely not abolish teachers altogether, this direction of travel will change the quality of teaching work and the relationships teachers have with students. That will be bad news for the students who are in most need of the care and support that comes from human teachers in the room, and of the motivation and social sense-making that comes from interacting with other students.

Risks to critical thinking

Far more than any risk to learning relationships, the mainstream media worries about GenAI threatening students’ ability to think for themselves.

When I started this substack it was to share my research and thinking about criticality – about critical thinking, critique and critical pedagogy - in the context of rapid change in knowledge practices at university. Generative AI has suddenly become that context. However, just because I’ve researched and thought about the issue a lot, I know it isn’t straightforward. There is a conservative narrative that goes something like this. If students aren’t using the same tools for thinking with that I used when I went to university, they obviously aren’t doing it properly. Standards are falling. Literally anyone can get a degree! There are also scare stories about digital technologies rewiring student brains (reveal: they do that, but it isn’t especially sinister).

So I’ve written a separate post about criticality and critical thinking that hopefully doesn’t fall into the conservative trap. I focus instead on what generative AI is doing to our shared knowledge ecology and therefore to the kinds of knowledge practice that are possible, or easy, for students to adopt. The risks I describe are changes to search, the capture of public knowledge, and what I have explored elsewhere as the management of textual labour for profit, including the work students input as they write their assignments, and the work they are likely to be doing as graduates in the near future. My concerns are for our collective critical resources, rather than individual student brains falling into disuse because of too much ‘artificial’ support. I’ll post the links shortly!

Meanwhile, there are other risks to student safety and wellbeing.

Safety and wellbeing

Every Head of IT and CIO in every university must now be familiar with the GPT-4 system card, published in March 2023. They are the people responsible for ensuring the safety of platforms provided and recommended to students. Here is a summary of the risks that must be keeping them awake at night (the ones OpenAI is prepared to admit to):

Considering only the last of these, OpenAI confirms that:

“[GPT-4 hallucinates] in ways that are more convincing and believable than earlier GPT models (e.g., due to authoritative tone or to being presented in the context of highly detailed information that is accurate), increasing the risk of overreliance.”

Over-reliance here means relying on outputs that are wrong, and OpenAI (as we have seen already) indemnifies itself against any harm caused. A global pandemic is not far behind us, if we need reminding of the risks to personal health from online misinformation. Generative models are known to have amplified the risks of disinformation campaigns and influence operations that damage democracies and democratic participation. And there may be more direct risks to mental health too. Students are using ChatGPT extensively for social and emotional support. Snapchat has integrated ChatGPT directly into their product as ‘MyAI’, so that its 750 million users have an ever-ready friend. Chatbots are friends who will always support you, even while you are being groomed by an older man or finding reasons for ending your life. The mental health concerns around MyAI in particular are set out on a number of web sites aimed at young people, and they include negative self-talk, violations of privacy, compulsive buying and emotional dependency.

These are not grounds for ‘banning’ generative models any more than universities could ‘ban’ social media. But teachers now introduce social media into learning with great care. Students are shown the norms of exchange in an academic or professional environment, and given access to spaces that are moderated according to those rules. It’s widely recognised that open online spaces are particularly toxic for some students, and opt-outs are available as well as targeted support. At the moment, no such alternatives exist for generative AI. Students must use the foundational models, with all their problems, or find more specialist apps that may only amplify the problems and add their own.

I admit to finding my exchanges with Bard and Chat GPT quite disturbing. A first person without a person, robustly confident but never having an opinion, humbly sorry but never responsible for its mistakes. These dissonances reflect the underlying architecture, so the models will always be limited by them - the normative rules, the viewpoint from nowhere, the relentless tracking to cliche. And yet the interface will only become more compelling as its outputs becomes more tuned to our personal needs and responses. An echo chamber that doesn’t even require other people who think like us.

As with social media, there are risks that students may give away private information that could be used against them, or be subjected to deep fakes. Students whose written work is uploaded to any of the proprietary platforms may have it scraped for training new models, or sold on to other developers, or used for any downstream publication without recognition, all entirely legally. Students are contributing, like it or not, to developing educational chatbots and artificial tutors that will disrupt their learning relationships and those of other students.

Universities have accepted a duty of care in relation to social media, running Safer Internet Days and targeted activities at induction, and developing comprehensive codes of conduct. These precautions I hope will emerge in relation to generative AI. But even in the good old days of web 2.0 zeal, I don’t remember social media being introduced to students as though every risk was a learning benefit. Yet that seems to be the trap we are stuck in with Generative AI, its inaccuracies, misrepresentations, bad referencing, cultural biases and privacy concerns are all opportunities to ‘build AI literacy’. Of course i believe in empowerment through knowledge and agency. I am an educator! But this feels like a perverse framing of student safety, in relation to a completely unproven technology. And the powerful corporations that have developed the technology are already running to distance themselves from these harms, leaving schools and universities to own them.

Thank you for this beautiful article (https://lnkd.in/eE64d_T8), but I do not agree with you at all.

I am afraid that artificial intelligence detection applications give 0% results for any product made by artificial intelligence applications such as Chat GPT, Bard, Bing Chat and other similar applications.

I myself tried these applications and found that their accuracy may be 0% because I produced a two-page text in GPT chat, and when I presented it to Turnitin to check the percentage of using artificial intelligence, I found it giving me a result of 0% for using artificial intelligence. While all the text was produced by artificial intelligence. Another very famous application was also used to examine these matters and presented it with the Bible and the American Constitution, and its result was more than 88% of the production of artificial intelligence.

Therefore, I have a completely different point of view than the one you mentioned in the article: In the event that the detection applications of artificial intelligence gave me 0%, this means that there is a very high possibility that this text was generated by artificial intelligence. But if the percentage is high in the use of artificial intelligence, then this means that there is a high quality of the text written by humans and not with the help of artificial intelligence. In reality, the matter is completely opposite.

Therefore, if you were my student and I had 0% of the use of artificial intelligence for the text that you prepared, then this makes me, as a responsible lecturer, assesst your assignment face to face with you, because this percentage gives me the impression that you used artificial intelligence applications in producing the text. As the current applications of artificial intelligence cannot in any way be detected by applications that detect the use of artificial intelligence such as Turnitin.

If you have another point of view, please provide it to me.

These are some sources that support my point of view. I very much appreciate what you presented and what you put forward through your point of view, and I look forward to more discussions on this topic with you:

How AI Detectors Mistakenly Identify AI as the Author of the Bible? https://lnkd.in/evmWDWwm

The Influence of Flawed AI Detection Applications on Academic Integrity: https://lnkd.in/ecDJ28Ac

Artificial intelligence text detection applications are a very effective cheating tool for students use to cheat. A short practical story: https://lnkd.in/eHB2hg6f

Colleagues around the world, kindly avoid suggesting AI usage in student reports..: https://lnkd.in/eGFwHs7k