Risks to teaching as work and teachers as workers

This could be a long picket line...

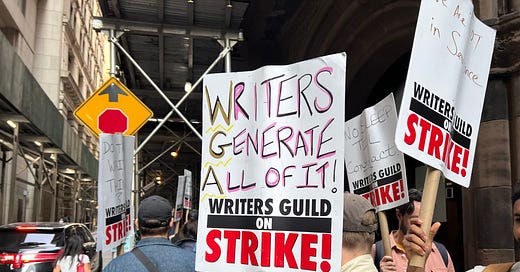

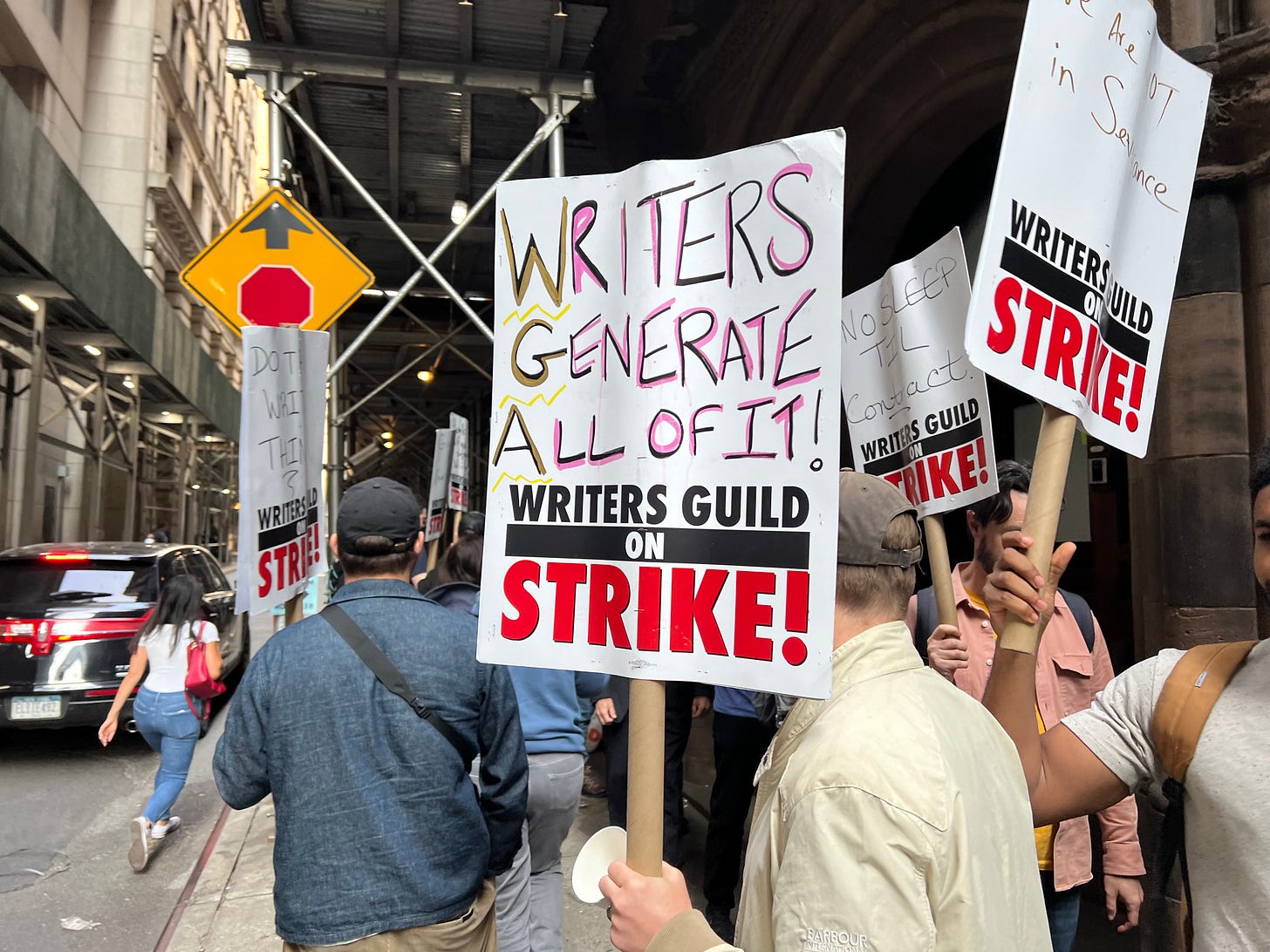

Earlier this year the Writers’ Guild of America (WGA) launched a rolling strike, protesting the threatened use of AI to replace script writers. In this industry, AI is a giant thumb on the scale that has so far kept creative labour in some balance with platform economics. This week, actors joined them, agreeing to the WGA’s demand that:

‘AI can’t write or rewrite literary material; can’t be used as source material; and [works covered by union contracts] can’t be used to train AI’.

Artists and illustrators have launched a ‘No to AI generated images’ campaign, and issued an open letter denouncing the ‘corporate theft’ of their work. Beyond the short-term losses, which the AI industry is not bothering to hide, the signatories foresee a future in which image generators like Midjourney and DALL-E have sucked human creativity from their profession. They see GenAI – at least in corporate hands - as ‘vampiric’:

feasting on past generations of artwork even as it sucks the lifeblood from living artists. Over time, this will impoverish our visual culture.

Music makers have joined artists in signing up to the Human Artistry Campaign, which asks reasonably for creatives to be involved in the design of AI regulation going forward. Less probably, the campaign demands:

Complete recordkeeping of copyrighted works, performances, and likenesses, including the way in which they were used to develop and train any AI system… Algorithmic transparency and clear identification of a work’s provenance … standards for technologies that identify the input used to create AI-generated output … and methodology used to create it.

In relation to the foundational models at least, that ship has long since sailed. But what the copyright argument clarifies is that the more public an artist or performer you have been, the more you have tried to communicate a unique quality or vision through your work, the more likely those qualities have been sucked into an indiscriminate vat of content and treated as a quantity to be exploited. The same is true of public educators and of the open educational resources they have shared.

Journalists have also begun to push back against the appearance of AI-generated copy. As reported recently in the Verve, editors at tech trade publisher CNET became aware that AI was being used to produce news stories and found that:

the robot articles published on CNET don’t need to be “good” — they need to rank highly in Google searches so lots of people open them and click the lucrative affiliate marketing links they contain… there’s no real reason to fund actual tech news once you’ve started down that path.

Financial and tech news may be particularly vulnerable to GenAI due to its predictable content. The same is true of the marketing copy that makes up a considerable portion of many ‘news’ sites:

But GenAI is moving along these pathways into every area of journalism. Now the laughs have died on all the ‘ChatGPT wrote my column!’ reveals (oh, how we laughed), we begin to learn of mainstream newspapers ‘experimenting’ with GenAI to decide how many staffers they can lay off. In this same article, the CEO of German media giant Axel Springer explicitly tells employees that:

‘Only those who create the best original content will survive.’

Not many journalists will pass this advanced Turing test, and those who do will have to fight off constant competition to be the ‘originals’ in the content production system. And GenAI will be challenging for those roles as well. Based on probabilistic calculations, it can already be tuned to provide ‘creative’ outputs (Bing Chat provides this option) so long as ‘creative’ is defined as ‘possible but unlikely’ in the text record. This definition of creativity will favour writing that is outrageous, improbable and disruptive over writing that is considered, complex, and meaningfully different, even when a human being provides the copy – because we don’t have enough of that kind of thing already. And while these ‘original’ writers might be working in ways that look like journalism as we know it, they are unlikely to have come up through the ranks of jobbing journalists, through a community of shared work and values. Because the jobbing journalists are probably working as fact checkers somewhere else in the human-text value pyramid.

What teachers do

Teachers are not content producers, and yet we do produce a lot of content – lectures, slides, hand-outs, diagrams, assignments and assignment briefs, examples, marking rubrics, explanations. In the Guardian, Hamilton Nolan explicitly ties the future of journalism to the future of other careers involving text and image production, and suggests that:

‘Unions are the only institutions with the legitimate ability to build guardrails for the humans’. The WGA dispute is, he says, ‘meaningful to you, and me, and everyone whose job seems to always be becoming more of a grind’.

‘College professors’ are among the grinders Nolan is concerned about. Professionals who produce a lot of content and have seen their rights over that content eroded, whose jobs have become increasingly precarious and who are asked to work ever more productively and ‘at scale’. So far, the use of GenAI has not been added to the list of grievances over which teachers in schools and colleges are taking action. But teachers are vulnerable in some of the same ways that hacks and actors, musicians and illustrators are. Open and public educators in particular have contributed extensively to the records that GenAI is trained on. In the past, having access to educational resources did not mean that students were teaching themselves, but add a shonky natural language interface to the front end and apparently now they are.

Computer scientist Prof Stuart Russell predicts that ChatGPT will be used to deliver ‘most material through to the end of high school’ and this will lead to ‘fewer teachers being employed – possibly even none’. He is not alone. As with journalism, the real risk is not that teachers will be replaced but that the work of teaching will be differently defined and organised and valued, partly thanks to hype like this. Perhaps (some) teachers could become the equivalent of the celebrity column writers, singled out for creative and charismatic qualities that can be ‘leveraged’ through the content mill. For other teachers, the work left over would be – according to Russell - ‘playground monitor[ing]’, ‘facilitat[ing] collective activities’ and ‘civic and moral education’. Which is fine if you like doing those things, but it doesn’t sound highly valued or paid. And the spectre of teachers being ‘replaced’ is a useful one if you want to ensure compliance with some big changes in teaching work and conditions.

What teachers don’t do

The stressful working conditions that teachers are protesting about will help to make GenAI more attractive. Saving time is how it is being promoted to teachers, and who does not want to free up time from repetitive work for more interesting aspects of the job?

But there is a catch. Who defines what is interesting and valuable for teachers to do? BS Skinner thought he could. Back in the 1960s, he called the non-interesting parts of teaching ‘white-collar ditch-digging’, something I learned in this rather wonderful essay on automation by Jeff Nyman. Skinner thought the difference between ditch digging and high value teaching was obvious, and always the same, for teachers and students everywhere. Of course Skinner had his own ditch-digger or ‘programmed instruction’ machine ready, and he set about breaking down the work of teaching into such small components that almost every part could be automated. The role of the classroom teacher would then be looking after the machine, and adding ‘empathy’, when empathy was needed. (Funny, isn’t it, how this residual, non-mechanical teaching person, this playground monitor with empathy, seems so… female?)

But teachers are whole people, and teaching is a complex, emergent relationship. Like other creative work it is oriented on how someone else takes meaning and value from what you do. Like other creative work, it is hard to know what that will be. Will your empathy, your charisma or your careful reasoning make the difference today? Because students and knowledge are so diverse, teaching has to be nuanced and contextualised in many different ways, sometimes in planning, sometimes on the fly. The answer to the question of what matters in teaching is, as Skinner eventually discovered, ‘it depends’. An AI tool may be helpful when an experienced teacher judges is can be helpful in a particular context or for a particular student (group). But what if the decision is made by the teacher’s college, as part of a procurement deal; or by an AI engineer focused only on student test results as outputs; or by a chatbot using student responses to determine how much teacher contact time they should be allocated? Then teaching work and teaching/learning relationships are changed in ways that do not feel empowering. Teaching may become more ‘productive’ in terms of student through-put, but less rewarding, less agentic, and less secure.

Pathways to profit

Far from being speculative futures or even collateral fall-out, the loss of jobs and job security is central the GenAI project. Without pathways to profit – through reduced labour costs, enhanced productivity, or click maximisation – GenAI would never have achieved the influx of corporate finance and computing power that allowed its foundational models to be built. Thanks to the personable interfaces of ChatGPT and Bing, users may feel they are the ones being wooed, but corporate partners and organisational users are the real clients. Microsoft is the main funder of OpenAI; Google is running to catch up with a series of enterprise-focused partnerships. GenAI is now being integrated into office tools, search engines, developer platforms and even the APIs that allow systems to interface with each other. GenAI is becoming part of the data and information infrastructure of every organisation, including every university. A recent Stanford study, gleefully reported by Bloomberg, claimed a 14% productivity boost in the first year of incorporating GenAI into workflows.

The real sell, then, is teacher productivity, and the real buyers are employers. But a partnership between the Khan Academy and Open AI suggests that a bigger prize - Skinner’s prize - can be pursued at the same time. Khanmigo (Khan academy + ‘amigo’, get it?) offers to ‘open up new frontiers in education’:

‘building more tutor-like abilities into our platform within the next few years, while also providing capabilities we had only dreamed of before.’

The specific dream is the ‘ability—to have a human-like back and forth… asking each student individualized questions to prompt deeper learning.’ As I found in my own explorations – and as teachers in the Khanmigo trials seem to have discovered – the generic language models are not very good at this. They struggle to ask even simple questions without giving the answer away. It takes considerable adjustments and refinements on the part of teachers to produce any kind of useful pedagogic exchange. Ben Williamson in a recent post, and Carlo Perotta in a more extended lecture, both comment on the adaptations reportedly made by teachers to get the Khanmigo chatbot to ‘work’ as it was meant to. But never mind, because like hundreds of other Gen-AI-in-education start-ups, the Khanmigo chatbot will benefit from working ‘alongside’ real teachers in its pilot phase. And this is where it is so important to understand how GenAI models depend on human labour. These interactions between teachers and students provide a specialised set of training data that will align Khanmigo better with its target ‘behaviour’: the ‘human-like back and forth’ of automated instruction. At least as important for the business model, the students will be learning to love Khanmigo. They will learn that the chatbot is worth their attention, that it can be trusted, that its outputs can help them learn, and that if its outputs don’t seem to be helping them learn, that’s a problem with how they or their teachers are using it.

Whenever a teacher helps to pilot an application like this, or uploads their own teaching materials and examples to a chat interface, or ‘upskills’ themselves in prompt engineering to produce a better experience for their students, they are refining the models that will enable the work of teaching to be reorganised and revalued. And Khanmigo is only one among thousands of education-related start-ups looking for a share of the large language model boom. OpenAI’s own analysis of the ‘exposure’ of different occupations to the impacts of GPTs found that the higher the level of education required in a job role, the greater its ‘exposure’ (meaning workers left out in the cold). Within that overall picture,

the average impact of LLM-powered software [i.e. sector-specialist systems] on task-exposure may be more than twice as large as the exposure from LLMs on their own…

And:

The distribution of exposure… could be more highly correlated with investment in developing LLM-powered software for particular domains.

The education sector, after finance and medicine, is the most lucrative market for these domain-specific systems.

Of course, large language models don’t have to be used against the interests of teachers as workers. Communally owned and governed, consensually trained, they could be a way of sharing practice at scale. They might enrich the work of teaching with insights from millions of teachers and learners. There would be risks as there are to any online commons, from power imbalances and asset grabbing to echo chambers and micro-tribes. But there could at least be shared processes for addressing them. I am really excited to follow how Wikipedia and the Wikimedia foundation plan to respond to LLM developments, for example. But without such collective solutions, we are just adding value to the underlying language models, and the data capital of the tech giants that own them. As the next turn of the screw of platform capitalism, GenAI will only tighten the logics of productivity: teaching ‘at scale’; unbundling and deskilling of teaching tasks; drill and kill assessments that are easy to auto-generate and auto-grade; fully self-service admin; outsourcing; datafication; and expropriation of teachers’ rights over their materials.

Or, as AutomatED puts it:

the true horizon of automation in education becomes apparent – not lights out automation, but the apprehension and control of educational practice and leadership in the name of managerial accountability. Not robots in the classroom, but teachers acting in standardised and predictable ways, unable to operate autonomously when unplugged from the digital infrastructure.

From hollywood actors to contract copy writers in the global south and game developers in China, GenAI is threatening jobs and the relationships people have to their work. Contractors who write for these ‘AI models’ are beginning to push back at their conditions too. And yes, it is becoming increasingly obvious that what these contractors do is also writing - that these supposedly brilliant models are simply platforms for extracting value from human writing - and that the business model is to stratify writing workers into different layers the better to extract value from them. The conditions of these text labourers are the exact mirror image of worsening conditions for workers like teachers and journalists at the other end of the pipeline. But by treating all creative work as grist to their words-profit mill, GenAI corporations may unwittingly be helping workers everywhere to join the dots.