Things don't only get better

Breakdowns, billionnaires and how not to save the planet

I’m sorry to run another ‘told you so’ post, so soon after the last one. It doesn’t make me a nice person. But unless you’re pathologically convinced by your own opinions (and I’m not) you have to grasp at every sign.

So, in my post on AI rights and human harms I said that general models (such as ChatGPT) may not keep getting better and better, despite all the claims of ‘exponential’ improvement and ‘artificial general intelligence’ being only a few upgrades away. I based this thought partly on reading experts in cognitive science, like Iris van Rooij and her colleagues, who find the idea of an ‘artificial general intelligence’ ‘intrinsically computationally intractable’ and conclude that currently existing AI systems are ‘at best decoys’. I based it partly on reading experts in general modelling (see my post on Sora). But mainly I based it on the business behaviour of our silicon chiefs, who are clearly more interested in pimping chatbot interfaces and distracting us with new products than improving the underlying models. Which they would do if it was easy.

As it turns out, fifteen months on from ChatGPT, Gemini and Claude are a bit better than GPT4 for some things. GPT4 actually seems to be getting worse. Just in the last week, Gemini had to send suspend its text-to-image generation capabilities and go back to the drawing board with its guardrails, and ChatGPT underwent a complete meltdown into gibberish. Both events show that the behaviour of models can be transformed by the tweak of a parameter over at Google/OpenAI HQ. Let’s hope the people in charge of all this continue to be regular, well-adjusted, public-spirited citizens. And both events show something else: nobody actually knows how to deal with the bias, the nonsense, and the hate. Guardrails are a guessing game. It’s black boxes all the way down.

Meanwhile the long-anticipated GPT5 is further delayed, and Sam Altman is rowing back hard on expectations, suggesting that he might have come to regret the promise of:

‘a recursive loop of innovation, as these smart machines themselves help us make smarter machines’

Instead, he admitted in November that ‘We have to figure out some very hard science questions to [get to GPT5], we have to go build more computers’. To achieve this, he is looking for $5-7 trillion to invest in chip production, in the hope that throwing more data and compute at the hard science will break it. To put this in perspective, the entire global semiconductor industry is worth about $500 billion a year. It cost the US $5 trillion in today’s money to fight world war two. So Altman is looking to fry the planet, deplete it of rare earths, exploit tens of thousands of data workers and aggregate more value in a single company than the entire militarised US state of the mid 20th century, all in pursuit of an upgrade he can’t be sure is there.

In 2021 he promised businesses:

phenomenal wealth. The price of many kinds of labor will fall toward zero once sufficiently powerful AI “joins the workforce.”

What businesses have got is mainly a new feature in the Microsoft suite that they are not sure is worth the price tag. In coding jobs, where a version of CoPilot has been used for much longer, the evidence is that the quality of code has degraded. Challenged by business leaders to explain their strategy for improving models - models that have now been built into major infrastructures and workflows - the CEOs of Anthropic and Google’s Deepmind admitted last week that ‘hallucinations’ are intractable and ‘we’re not in a situation where you can just trust the model output’. Other challenges, such as the huge costs of training and running them, hoping the copyright infringements don’t come back to bite you, and ensuring sensitive data is not leaked: these ‘don’t yet have clear solutions’ either.

Phenomenal wealth has been generated, for sure. Billionnaire investors made 96% of their gains last year by betting on AI stocks. At the same time, the tech industry they are investing in has decided to slash its workforce, because AI. But no-one apart from the billionnaires seems to be feeling phenomenal. Not yet anyway.

Saving the planet, one cute animal video at a time

In other not-getting-better news, the climate costs of generative AI are becoming a concern. Although the companies that train and run them are intensely secretive on this point, Kate Crawford has gathered some of what we know in a review for Nature, and calls for legislation to stop power and water conservation becoming casualties of AI competition. This seems to have written before Sam went public on his plans to power up 5 trillion dollars worth of chips.

Energy expert Alex de Vries, speaking to the Verge, has calculated that by 2027 AI will be using at least as much energy as the Netherlands. This is less than one percent of global energy use - the Dutch are a frugal people - but for what? Image and video synthesis is far more costly than text, and text inference is far more costly (4-5 times) than a standard search. So those cute videos are turning a lot of fresh water into steam. It does seem to me that as generative models are integrated into every interface - from working with business software to chatting with avatars in immersive worlds - it will become harder and harder to know what proportion of computer power is being used for synthesis. Or indeed where the demand might stop. Just the prospect of training future models has fuelled a massive data centre boom and made Nvidia the fourth largest corporation on the planet.

As de Vries points out, the problem is not really the current energy use (so far as this can be known), but the economy of large language models, that rewards the most computation- and capital-intensive practices with market capture. This is:

a really deadly dynamic for efficiency. Because it creates a natural incentive for people to just keep adding more computational resources, and as soon as models or hardware becomes more efficient, people will make those models even bigger than before.

In fairness, data-based approaches are vital in climate science, which is genuinely hard, and genuinely important. I read the recent UN report on AI and climate with an open mind. Allowing that ‘AI’ is now whatever data and algorithmic technique you want to throw magic dust over, there are valuable applications here. But all the cases explored by the UN use modelling in the context of other specialist workflows and systems. Not one requires a generative language model.

Wired magazine recently interviewed DeepMind’s climate lead, Sims Witherspoon, who has more claim than most to be addressing these problems. Her takeaways on how AI can mitigate climate crisis are: 1. better forecasting; 2. optimise existing systems; and 3. nuclear fusion (something Sam Altman is also investing in heavily). So, yes, better intelligence is useful, but does not mobilise the necessary political, economic and social change to make an actual difference. And yes, optimising the systems we have today might flatten the upward curve a bit, but hi-tech fixes of this kind can delay and distract from the systemic change that is really needed: disinvestment from fossil fuels and a wholesale shift to practical green technologies. For the most part these technologies exist already. Nuclear fusion, not so much.

Sadly, 2023 saw a steep decline in investment in viable low-carbon tech, while venture capital was piling into AI. The big costs of AI to climate change will, I suspect, not be its energy consumption but the lost opportunity to invest in viable solutions while there is still time. So long as ‘smart machines’ to solve ‘hard science’ keep sucking up the dollars, high finance and high tech can keep sucking up the profits. And if their bet on as-yet-unviable, unscalable future technologies like fusion fails to pay off, the billions they have amassed can at least furnish their bunkers. For the rest of us, the Matrix will now be available in high resolution.

Neither fantasy nor fatalism

‘AI’ is not a technology, it is a story about the future. A story with more power than most, but a story all the same. Powerful computational techniques do exist, new ones will continue to be developed, and some of them will be used to help manage (model, predict, optimise) the existential threat of climate disaster. But there are other, more pressing stories about what needs to be done.

The knowledge and data economy is built on the foundational economy. It depends on the productive ingenuity of human minds in human bodies, that need food, water, shelter and care. It demands a material abundance of rare minerals, energy generation and network infrastructure. So-called ‘AI’ is continuous with other productions of human culture, and with the natural world, however its Titans may long to break free. And since it is contributing so impressively to war, wealth inequality and democratic breakdown, I don’t think a few contributions on the side of climate science are really enough to level the balance.

Of course, higher education tells different stories about the future, and I don’t find huge enthusiasm for the one with the chatbot takeover. But I do detect a lot of fatalism, particularly about the futures of work, that I think should be challenged.

In the first of our new podcast series on generative AI, my colleague Mark Carrigan and I discuss ‘AI realism’ as an alternative response to either fantasy and fatalism. These models are now an integral part of educational infrastructure, formally and informally. That is simply the reality.

Hours of precious academic time has been spent reviewing guidelines and revising assessment regimes. These create new realities too. Much as they did when the internet came along, and then with social media, academics and professionals have worked with students to develop positive practices, taking into account their wellbeing as well as their intellectual development. This matters far more than any writing of mine. I don’t think any of it has been easy, and generative AI is probably going to make it harder, both in its own right and as it hastens the platformisation and enshittification of the rest of the online world.

Realistically, I hope the resources and the risk assessments are there to help everyone cope with this new present. Realistically, I hope I have pricked the AI fantasy a little, so alternative stories have more space. I really look forward to conversations about alternative futures we and our students can hope for.

A bit of personal news: the substack will be going quiet for a while as I focus on urgent writing deadlines. Look out for the podcast series: Generative Conversations with me and Mark Carrigan, and some fabulous guests. You’ll be first to know when I get back online here, perhaps with some new issues. I don’t want to become a one-trick generative pony.

Some time after we (the general public) first heard about ChatGPT, I wrote a letter to The Guardian, in response to an article by Evgeny Morozov, titled: The problem with artificial intelligence? It’s neither artificial nor intelligent. 30 March 2023. In my letter I said:

AI’s main failings are in the differences with humans. AI does not have morals, ethics or conscience. Moreover, it does not have instinct, much less common sense. Its dangers in being subject to misuse are all too easy to see.

It seems that, one year later, these issues have not begun to be addressed and the tech companies basically have no clue how to address them. Nor the interest.

Your line ‘AI’ is not a technology, it is a story about the future. ‘ - I’m in love with it!

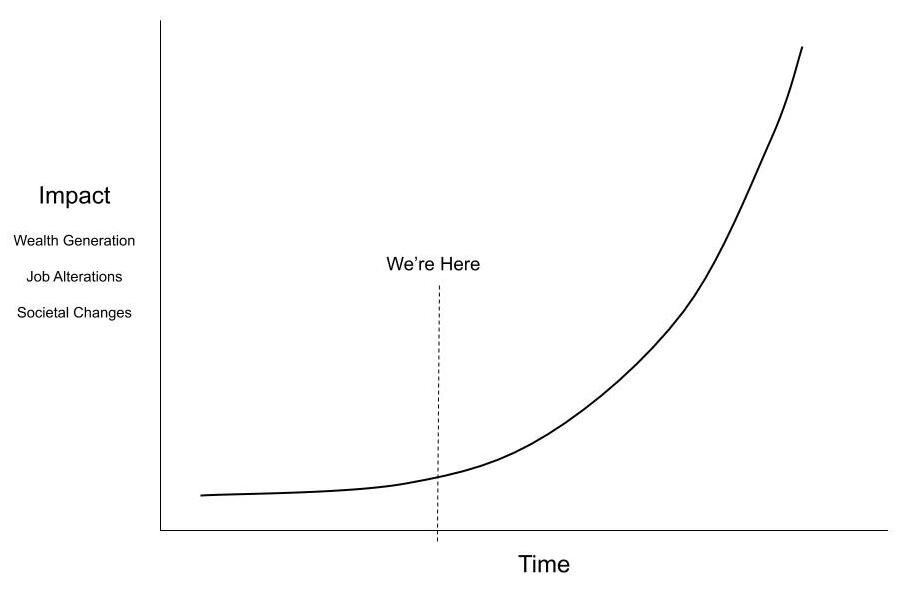

I’m constantly reiterating in PD and conversations with colleagues that we are at a moment in time where what we do now really matters.

How we teach students to see AI as something physical (to echo Crawford) with economic, political, social implications. As extractive. This is crucial futures work.

But staying in this space of critique needs to be balanced by the practicalities of the genie that’s been released. No engagement with the products risks stasis. Not blind pragmatism of course, but as you say, futures work.

I do look forward to the podcast. Thank you! Such important reading.