AI rights and human harms

From judiciary hearings in the US to a miscarriage of justice in the UK - should silicon have rights?

With judiciary hearings on technology and journalism in the US Senate last week, it was not a week for tech or media commentators to stay quietly at home. Cue Jeff Jarvis, director of a Centre for Entrepreneurial Journalism, who sees many opportunities for collaboration between AI and print entrepreneurs, if only the Gutenburg relic of copyright law could be consigned to history. He took the opportunity to make this argument for ‘AI rights’ (with thanks to @neilturkeiwitz for the link):

What indeed. Jarvis has since claimed he meant many of these terms ‘metaphorically’, and he is of course free to use words as he chooses. But it is hardly an original or an innocent metaphor. What is at stake in these hearings is whether a particular kind of innovation –generative transformer models - offer such extraordinary opportunities that companies should be allowed to develop them regardless of legal frameworks, cultural conventions and evidence of harm. And in this dispute, ‘learning’ is one of the key terms that has been co-opted by the AI industry to make their case.

Applied to generative models, the term ‘learning’ does several things for the industry, all of them here in Jarvis’ testimony. The first is to put so-called ‘artificial intelligence’ into a special category. Not the category of human beings, who the law endows with rights, intentions and responsibilities. But not the category of ‘ordinary’ technologies either, that are (in legal terms) just the means for doing what their users intended. (Designers and providers have legal responsibilities too, so you can see why a new category might be desirable.) This ambiguous category doesn’t seem to require that developers explain how their creations ‘learn’, though that troubles us in education (as it should). It does introduce an aura of mystery, or a fog of obscurity, around how they should be treated in ethics and law.

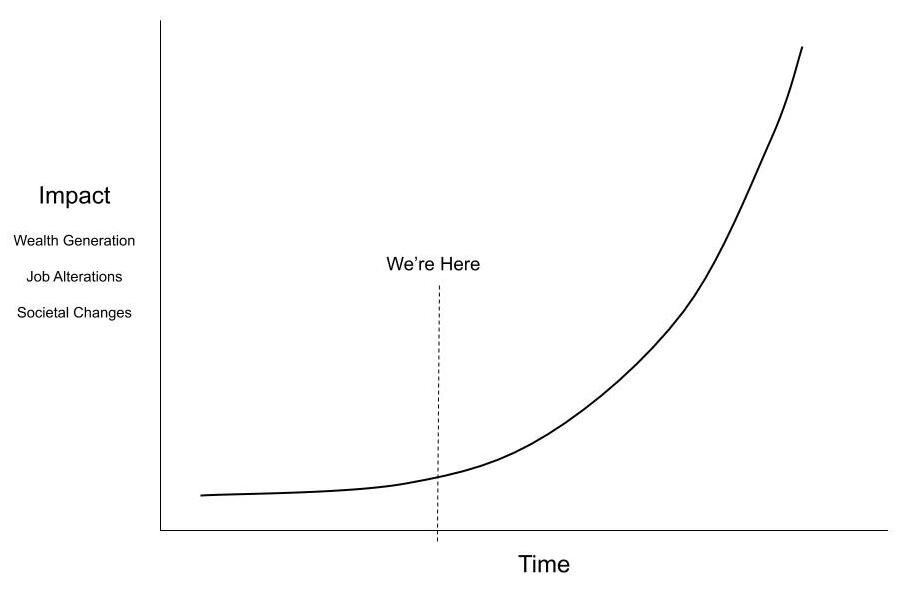

The second use of ‘learning’ is to produce heightened expectations. If these models can ‘learn’ (whatever this means), we can expect them to improve, and to go on improving. Just in case we have begun to feel rather disappointed with their actual capabilities, we are invited to think instead of their potential. They are ‘still learning’ and we are ‘only just beginning to learn what they are capable of’. All we need to do, for the familiar graph of better-and-better-ness to take off towards infinity, is to ‘allow them to learn’.

Machine learning already has many useful applications, but the reason you keep hearing the same use cases – medical diagnostics and protein modelling for example – is because the successes are specialised. Development is costly, including the curation of massive data sets from experimental or recorded data, gathered in the usual painstaking scientific ways. Developing and testing models can take years. The workflow is also specialised and often highly integrated, with other bespoke technologies such as sensors and robotics. Running the systems and interpreting the results requires human expertise too. ‘Machine learning’ models don’t just improve by themselves. They can be retrained and re-parameterised, they can be fed new data. But there is no autonomous ‘AI’ driving the process. And none of these paradigm cases involves a general media model (language, video, code etc) like ChatGPT.

The term ‘learning’, to you and me, suggests a general capacity. So not only do we imagine an endless, upcurving graph, but we think that all kinds of potential must be hiding in the space under the curve: a cure for cancer perhaps, or the solution to climate change. Not just a case-by-case development of new applications. Investing in ‘AI’ at the ‘we’re here’ moment becomes a moral imperative, an absolute priority for the future of humankind.

Now, last and most insidious of all I think, the use of ‘learning’ tends to make us think of childhood and its special rights and vulnerabilities. The universally recognised UN Convention on the Rights of the Child includes, alongside the right to education and development ‘to their fullest potential’, duties of care and protection. This is why Jarvis’ use of the term ‘right’ in relation to ‘learning’ is so significant. These rights are not metaphorical. They place real legal and ethical demands on states and education systems. It’s also, I’m afraid, a classic piece of culture-war what-aboutery: making the powerful seem vulnerable by asserting their need of protection.

But whose rights are really at risk in Jarvis’ testimony? Who or what is being ‘deprived’ of development? If we read closely, it is not the models at all, but ‘we’ who will ‘lose out’ if AI is not allowed to ‘learn’. This is not a coherent moral position. If models have rights, it can only be on their own behalf: their rights must relate to their own needs and purposes and vulnerability to ‘loss’, not to anyone else’s.

So what passes for moral philosophy in Silicon Valley really amounts to this: let big tech get on with doing big tech, without annoyances like legal frameworks and workers rights. The very last thing these corporations want is a new class of entities with rights they might have to worry about. They don’t want to give up valuable server space to failed or defunct models just because they ‘learned’ or once passed some spurious test of ‘sentience’: they want to decommission the heck out of them and make way for something more profitable. That is hardly a rights-respecting relationship. No, the models that big tech really cares about are business models and the thing they want to be accorded more rights, power and agency is the business itself.

Silicon lives matter

This is why we are seeing apparently rational, or at least sentient people calling for an AI rights movement, and tech advocates like Ray Kurzweil getting on board. For example, in thinking about AI consciousness, we are urged to reject ‘human bias’, ‘species chauvanism’ and ‘anthropocentrism’, terms taken directly from arguments for animal rights. The case for animal rights is a sophisticated and super interesting one, and I should get around to posting about it in relation to theories of ‘post-humanism’ (theories that also see technologies as having some kind of agency). But luckily I don’t have to step up to that here, because the tech guys are happy to use much less sophisticated comparisons.

When Nick Bostrom asserts ‘the principle of substrate non-discrimination’, he tells us that the idea of human beings having a different moral status to silicon systems is equivalent to ‘racism’. The difference between silicon and biology, like differences of skin tone (his definition of ‘race’, not mine), is something we should just get over. In similar vein, Ray Kurzwell reminds us, in response to a question about AI rights, that ‘it wasn't very long ago that women didn't have the right to vote’.

Nick, Ray, I’m sorry to have to break this to you, but struggles against racial and gendered oppression are still going on, in violently particular and non-metaphorical ways. These struggles are not badges of white, male broadmindedness (look, you let some other substrates have rights!) that you get to pin on some other issues you have decided care about. And while it is broadminded, in a way, to embrace silicon superintelligences as your brothers in arms, it does imply that it takes you a similar giant leap of imagination to imagine that women, or people of different origins to yourself, should have the same rights as you do.

A 2022 special issue of Frontiers in Robotics and AI: ‘Should robots have [moral] standing?’ includes a troubling essay that shows the problem even more clearly. The essay uses the examples of ‘servants’, ‘slaves’ and ‘animals’ to argue that what matters is how ‘virtuously’ the ‘owner’ behaves towards those in his power. The lived experience of slavery does briefly appear– so props to the author for realising that there might be an issue here – but in the end only to lament that the robot-slave metaphor is ‘limited’ by the unhappy particulars. Not that the ‘virtuous slave owner’ is a problematic moral guide. Not that human slavery should conscientiously be avoided as a metaphor for something else, such as the rights of non-human machines.

You are free to use the metaphors you choose, guys, but your choices betray your perspective. And in all these cases, the perspective is from someone with power. The power to choose, the power to behave nicely, or not so nicely, towards other people, women, servants, slaves, animals, chatbots, substrates. What these choices give away is a complete lack of understanding of the agency, the consciousness, the realities and perspectives and struggles of other people. The puzzle you can see lurking behind these examples is: where did all these rights of non-white non-guys come from? And the answer: it can only have been from the enlightened virtue of the white guys in charge. They decided that women deserved the vote, that slaves should be free. And in exactly the same way, they can decide to endow rights, privileges, consciousness even, to things they have created from their own incredible brains.

Human versus AI rights

I’m sure there are people in silicon valley who believe in what they call ‘AI’. But if they are interested in the rights of sentient beings, they might attend first to the harms being done to human beings where these technologies are used. Human rights are under attack whenever secretive, proprietary systems are used to make decisions with human consequences. Equity is harmed when those decisions are systemically biased. Decisions such as who can get credit, who has insurance and who should be investigated for fraud, who can cross borders, whose children will be taken into care, who will be targeted by automated weapons: Worker’s rights are infringed by the reorganisation, the precaritisation, and the intrusive surveillance that AI brings to work. And the businesses behind the systems very much do not want to be responsible.

These ethical issues are not at all theoretical. A twenty-year-long miscarriage of justice has been in the news here, thanks (in very British fashion) to an ITV documentary called Mr Bates versus the Post Office, and an expose by satirical magazine Private Eye.

The scandal involved the procurement of an IT system under one of the many privatisations beloved by the British state. Faults in the Horizon system – designed and delivered by Fujitsu - led to more than 700 innocent sub-postmasters being convicted of fraud. Dozens went to jail or suffered bankruptcy, thousands more lived with the shame of being accused, and at least four committed suicide. Leaders of the Post Office and Fujitsu committed perjury to protect their businesses. As the number of people accused of wrong-doing continued to climb, and as human lives became casualties, the computer system that was behind all the alleged cash shortfalls was considered beyond investigation. When cases came to court, juries were directed to find the testimony of the computer system ‘reliable’ but to question the motives of the accused employees (many of them of South Asian origin).

While corporations may assert that whatever they want to call ‘AI’ this week should have ‘rights’, what they actually want is to be relieved of responsibilities. They and their technologies should not be regulated or scrutinised. They should not be legally held to account, or at least, they should be considered more ‘reliable’ in law than the people whose lives they impact.

Big tech has so far blasted through anti-trust legislation to establish its vast concentrations of capital. It is attempting to overturn copyright law, to ensure it can capture and process any content that it likes. I predict that it will come for human rights and the laws that defend them. Why? Because there is mounting evidence that generative models, like all data models at scale, like all inexplicable algorithms and black box systems in the hands of powerful states and corporations, present grave threats to human rights. This is borne out in an excellent report by the Council of Europe, AI in Education: a critical view through the lens of Human Rights, Democracy, and the Rule of Law. the sections on human rights and democracy in particular should be read by everyone working in education. More broadly, a statement by Volker Turk, UN High Commissioner on Human Rights recently called on all states to take ‘urgent action’ to ‘embed human rights into every stage of the AI lifecycle’. If this does not happen, he predicts an escalation of present abuses and harms.

If we are to use the language of human rights, let’s remember that rights are not granted by the powerful to the weak, but are the best statement we have of a fundamental human truth. In the words of my dad, a lifelong campaigner and writer on human rights:

Human rights arise from the common needs that human beings have: the interconnectedness of his or her life with others as a basic condition of existence.

Thanks, Dad, for all the substrate.

"You are free to use the metaphors you choose, guys, but your choices betray your perspective." LOL!

I shall be borrowing this substrate for sure. ;-)