Writing as 'passing'

Turing tests, language games, and the instrumentalising of student writing

Last month I gave a seminar as part of the IoE Academic Writing series called ‘Student writing as “passing” and the role of generative AI’. You can find the recording here if you prefer to read with your ears. Thanks to the wonderful Ayanna for organising this event and for her ongoing investigations into student writing alongside synthetic text. Thanks also to the participants whose insightful questions and contributions helped to shape this post, and to Ayanna and John Hisldon for generous comments on it.

In this post I cover:

The Turing Test, and what it has in common with student writing, at least as writing is often experienced by students

Student writing as ‘passing’ in a world of deepfakes and generative possibilities

Beyond passing 1: student writing as identity work

Beyond passing 2: student writing as social activity

Beyond passing 3: student writing as expression and dialogue

Some practical ideas for writing beyond passing, many drawn from the seminar participants

In preparation for the webinar, I also wrote a post all about the Turing test, its implications for contemporary ‘AI’, and how it relates to theories of learning. That might be a good place to start if you want a deeper dive into those issues. Otherwise, here’s a brief summary on the Turing test before getting down to thoughts about student writing.

The Turing test

The Turing test is a thought experiment that remains at the heart of the ‘artificial intelligence’ project.

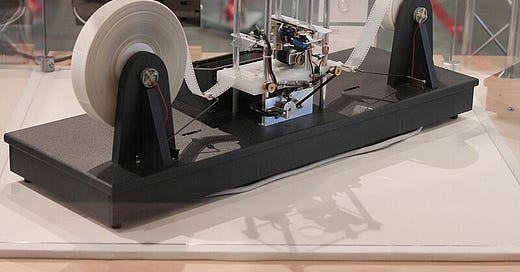

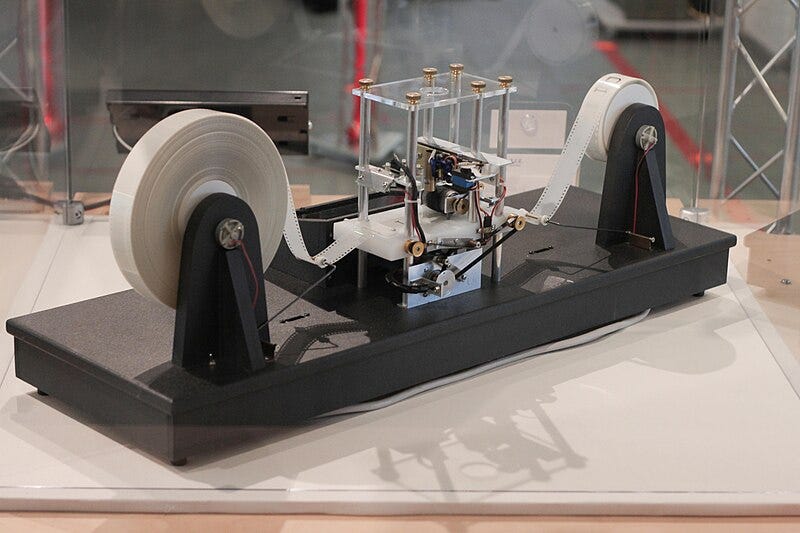

The classic version can be represented as a system of three players. The role of Player C – the ‘judge’ or ‘interrogator’ - is to question the other two players, who are a computer (Player A) and a human responder (Player B), and to decide which is which. Turing’s prediction was that by the end of the twentieth century:

‘an average interrogator will not have more than 70% chance of making the right identification after five minutes of questioning’

It is this capacity to fool people, or at least some of the people, some of the time, that is the goal and standard for artificial intelligence. It is a standard that is regularly claimed to have been ‘passed’ or ‘broken’, and since the first public generative transformer models were unveiled in 2022, those claims have come and gone as regularly as OpenAI has changed its ethics team.

The equivalent positions of human and computer, the insistence on disembodied ‘outputs’ and the comparative nature of the judgement are all used as signs of the test’s objectivity. The players are behind some kind of screen. Their bodies and voices are hidden, their responses limited to the passing of text messages. The human beings, then, are made to seem as much like automata as possible. Yet, as I show in my parallel post, the test is a maelstrom of misdirection, identity politics and hidden desires.

Student writing as ‘passing’

In my talk I outlined some similarities between the Turing test and student writing for assessment, at least as it is typically understood by students themselves. For example, the dynamics of the situation place students on the other ‘side’ to their academic assessor, visible only through a screen. Text is the preferred medium, reducing opportunities for interactions of care and concern that may previously have existed among the players. The judge can ask anything they like, and their decision is highly consequential. Ultimately, ‘passing’ as a graduate really does confer a new identity. But meanwhile, every time a student offers up work for judgement, they are being compared with other students who may appear to be more credible, more ‘passable’, less of a fake.

There are many reasons why students may feel that they are not credible as ‘real’ students, or ‘real’ producers of text. Synthetic text promises, on the face of it, to allay these fears.

Yet while it offers to help students ‘pass’ each assignment, overall synthetic text only adds to the anxiety about passing. The norm for comparison – in students’ minds at least - is now an AI-augmented student, perhaps one with access to better models or AI writing services, or with more confidence to use AI and not get caught. Students may feel they are contending directly with text automata, their faultless grammar and authoritative tone becoming the new norm against which ‘real’ student work can only look inadequate.

And students may justifiably feel concern about failing the Turing-equivalent test of ‘AI detection’. Having your text identified, rightly or wrongly, as emanating from a bot may mean becoming a non-student, or at least being subjected to investigations that further undermine your sense of validity. In the absence of any certainty, on either side, about how ‘AI text’ can be detected, the best strategy for passing may not be the straightforward one – to write unmediated – but rather to second-guess what ‘unmediated’ looks like from the other side of the screen.

The dilemma of writing authentically in a world of synthetic text is the same dilemma facing every content producer in a world of deep fakes. Here’s Rob Horning in a brilliant recent substack post on the tension between realism and ‘the real’:

Horning goes on to define the ‘deep real’ as a representation that aims ‘to subordinate events to their potential status as content’. The real (event) gains currency only when it enters circulation, and it is the content economy that defines its realism. If we think about student writing through this frame, all writing as process (event) is sooner or later subordinated to its status as an assignment (content), offered into the system for submission, grading, and validation. The status of writing as ‘authentic’ is not given until it has ‘passed’ these hurdles, which like realism also have their modes and fashions.

None of this invites deep attention to the process or event of writing. Indeed, unlike in the US, UK students receive little or no attention to writing as a process. They may well have come through a school system that promotes the most instrumental kinds of text production, expecting a mark for every correct fact, and throwing in as many key words as possible. School students in the UK are trained to write for a highly automated marking system, even if teacher labour has not been fully automated. And this is true of education systems around the English speaking world. As a result, large language models are trained disproportionately on text that has already been optimised for such systems.

For students, university writing can seem an unassailable mystery even before the mysteries of assessment. It is a black box all of its own. You learn stuff. You write stuff. Who knows what happens in between? It must not be cut and paste. It should not be auto-summarise, or auto-generate. And yet these processes work, in a way that is not at all guaranteed by the recommended methods of note-making, observation, reflection, discussion, planning, analysis, ideation, argumentation, position-taking, translation, disputation, editing and re-editing, and all the iterative adjustments between the whole and the parts that constitute thinking in text. However, we can try to open up the black box of writing, and later sections explore how some teachers of writing do this.

Unlike Turing, academics also try to open up the black box of judgement and explain to students the criteria by which their writing will be assessed. But in being made explicit, qualities of writing can be further instrumentalised, and can even become data models of the kind used in automatic essay scoring. (It seems worth noting here that, after decades of investment, AES systems remain barely useable, unless their purpose is to skew student writing permanently towards those surface features that automation can measure, and away from all other considerations of value. One good thing to be said for AES, however, is that ChatGPT is worse.)

Today’s large language models are evaluated against qualities that sound a lot like marking rubrics. ‘Readability’, ‘insightfulness’, ‘completeness’, even ‘metacognition’. Every measure in the FLASK evaluation set (shown above) is a statistical model of a quality that was originally judged by human assessors. As you can imagine, among model developers there is a strong incentive to integrate these benchmarks into the model training process, ensuring that outputs are already aligned and the model is likely to perform well on benchmark tests. Just like marking rubrics, benchmarks skew performance towards values that can be measured, and towards norms that have already been standardised.

Retraining is a long and expensive process. As a short cut, model engineers also use system prompts to adjust performance. System prompts are natural language instructions that are typically added to the user prompt to direct outputs. Versions of ChatGPT’s system prompt have been widely circulated, and they read in parts like the kind of general guidance that might be given to a student writer, perhaps in a slightly more instrumental tone:

Organise responses to flow well, not by source or by citation

Do not regurgitate content.

Make choices that may be insightful or unique sometimes.

Never write a summary with more than 80 words.

Integrate user suggestions.

So synthetic text arrives into a regime of writing and assessment that is already instrumental and transactional, tuned to measuring what can be measured rather than supporting personal development or diverse voices. Without being fully synthetic, student writing has already been pre-automated in order to pass through university platforms: submission systems, plagiarism detection, automated marking and feedback, progress/grade dashboards. Student writing might already feel a lot like passing textual tokens through a screen. Particularly as rising teacher/student ratios and reduced teaching time mean that the different players, just like Turing’s, may hardly know each other at all.

Student writing as identity work

How can we enable students to experience writing as more than transactional?

A text that influenced my thinking on this subject was Mary Lea and Brian Street’s (1998) Student writing in higher education: an academic literacies approach. (The link is to a great retrospective article on the book and its impact.) Lea and Street see ‘disciplinary practices of reading and writing’ as constantly evolving and being contested over, as well as becoming authorised and passed on. The academic literacies that students develop are not just skills with text but are ways of relating to their subject of study, and negotiating a place in that discourse community. Literacies are ‘concerned with ...identity, power and authority’.

In Writing as Identity (also 1998), Ros Ivanic considered how the process of writing asks us to manage several different versions of ourselves. There is the ‘autobiographical self’ through which we tell our ongoing life story, and which has brought us to the point of writing. There are the various sociocultural roles we are offered to adopt as writers, for example in relation to the university and its arcane processes for authorising texts and people. In writing, Ivanic distinguishes also the ‘discoursal self’, which we might think of as writing style or voice, from the ‘authorial’ self, which we might think of as position or stance – how we construct the ‘I’ of the text, and take responsibility for its arguments, observations and positions.

I’m not convinced Ivanic’s different selves can easily be untangled, but what her work does help me to think about is how identity is at stake in writing. How there is never only one identity, or only one outcome of the reflective dialogue between them: ‘In any institutional context there will be several possibilities for selfhood… [but some] of these will be privileged in the sense that the institution accords them more status’ (Ivanic 1998: 27).

How and what we write confers power and privilege as well as identity. Like spoken accent, writing acts as a sign of social capital, and a key to accessing further opportunities.

The magic of writing at university is that it really can produce a new identity. Graduation literally confers this. The hope is that by learning to account for themselves in writing, students produce new resources for autobiography as well as for accreditation. But writing is exposing. It is a bid for credibility that is public, contestable, ‘out there’, and may fail. Although universities have changed in many ways since Ivanic was writing, and are on the whole more diverse and more welcoming of diverse forms of expression, still their role remains to uphold the status of certain kinds of writing. And today’s students, used to the intense scrutiny and self-scrutiny of a life online, are more anxious than ever to maintain credibility when they express themselves, and more anxious than ever about comparisons with a norm.

I think most students experience academic English as a profoundly ‘other’ discourse. If they don’t feel completely excluded from it, they may feel they are writing in a voice that is not their own. All the more so if (some variant of) English isn’t their first language. One way of gaining a sense of ownership is to bring more personal or personally significant material into student writing, so that they have something to say (so that they feel like ‘authors’ of their own material) before they start to write. Hannah Ashley and Katy Lynn, in a lovely essay ‘Ventroloquism 001: How to throw your voice in the academy’, report that this approach gives students greater confidence for writing.

Some students will feel more comfortable than others working with personal material. And there is always a source of tension between the personally available and the authorised. But Ashley and Lynn see this, too, as a source of interest and identity work:

Practices that bring in the "I," like memoir and service [community-based] learning, provide students with an opportunity to see how their own private/community discourses are part of a particular set of popular/commonsense notions which get called into question when they butt up against a different community discourse. Ashley and Lynn 2003

What I like about their work is that they avoid calling student’s private/ community discourse ‘authentic’. They talk about students learning to recognise themselves as writers in dialogue with a host of speakers, writers and discourse communities, some of them authorised by the academy, some personally available, but all of them contestable. In this teaching practice, there is no ‘correct’ way of writing – not even one way of ‘writing as oneself’ – but rather a range of possibilities that students can explore.

Bringing the ‘I’ to writing does require students to take up a stance, even if it is a provisional and partial one that can be revised. In the context of a reflective classroom, ventriloquy or passing as a writer of one kind or another can be made more playful, but it can’t be made completely safe.

Today, as well as the spaces of higher education, students are negotiating their identities in digital networks and communities. So it does seem to me important that research into students’ use of generative AI also looks at how students are being constructed as writers by the AI industry and how they are also managing these constructed selves when they come to write. AI tools and services do not typically address students as producers of knowledge, or as negotiators of different perspectives, however we may encourage these approaches. They do not suggest identity as work, even of a playful kind. What AI offers is a magic cloak, a trick, a fully achieved writing identity. And this in a setting where other ideal selves are also magically available.

Student writing as social activity

I don’t think we can counter the allure of the magic cloak without looking a bit deeper into the theories of language that stand behind the AI industry – and they are different to the ones that have mainly informed practices of academic writing.

Computational linguists have often tangled with the linguistic ideas of Ludwig Wittgenstein, at least as they were expressed in his early Philosophical Investigations. In 1939 there was even an argumentative encounter between Wittgenstein and Alan Turing: his subsequent development of the Turing Test as a kind of language game is rumoured to have been a kind of riposte from Turing to Wittgenstiein (a reminder that I have written more about the Turing Test here.)

It was a student of Wittgenstein’s, Margaret Masterman, who first proposed that words could be represented as (mathematical) vectors describing their relationships with other words in a corpus of text. Her work made language computable without having to start from general rules of grammar or syntax. Each word can be expressed in terms of its relationships to other words. Unlike in formal grammars, new relationships can always be added on, making these models flexible, extensible, and particularly suited to data at scale. Vectors formed the basis of the first working search engines and information retrieval models. Today’s large language models are essentially massive vector databases.

Masterman’s approach can be traced back to Wittgenstein’s insight that definitions can be ‘by example’ or by family resemblance, rather than by logical equivalence. So Wittgenstein is held up (correctly, in my view) as supporting the conceptual shift within AI, away from propositional rules and towards probabilistic modelling. A useful recent article about this shift is called From rules to examples: machine learning’s type of authority. Another very accessible piece is Remembering Ludwig Wittgenstein in an age of AI.

However, neither of these essays, nor Masterman’s original work, take account of another insight of Wittgenstein’s, against which his idea of exemplary language needs to be set. ‘The speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life’, he wrote. It is the form of life, the ordinary activities or games people enter into with language, that give language its meaning. GPT4.o, for example, can respond to input text in a ‘context window’ as long as 128k elements. But however massive and inter-related the corpus may be, however impressive the ‘context window’, they are still just text. And Wittgenstein clearly intended by ‘use’ something more than ‘place in surrounding text’ or even ‘web of textual relations’. Wittgenstein meant the social, cultural and practical situations in which people make language work for them: ‘to imagine a language is to imagine a form of life’.

(Arguably, the to-and-fro dialogue between a user and a large language model constitutes a new kind of language game. I find this an interesting idea: but it is still one that would need to be investigated in terms of users’ emergent understanding and meaning-making, and not – in my view – as if the language model itself is participating in a form of life, in Wittgenstein’s sense.)

Margaret Masterman realised Wittgenstein’s first insight through the development of neural nets and machine learning. The Wittgenstein of ‘language games’ is found in other lines of linguistic thought, lines that throw into question whether language models can be said to ‘mean’ at all.

Critic Toril Moi sees Wittgenstein as a philosopher of ‘the exemplary, the public and the shared’. The exemplary in this sense is not the same as the ‘normal’, statistically calculated, but almost the opposite: a space for coming to terms with differences, for encountering the otherness of other people and their meanings. While statistical AI no longer tries to ‘fix’ language in grammatical and syntactic rules, it still insists on a fixed structure. A structure that expresses probabilistic rather than deterministic relationships. A structure that emerges from reams of public data rather than being constructed by self-appointed experts. But still, it is a structure that fixes text in the past, that is supposed to generate meaning while completely resisting any challenge or change.

And it is not the quantifiable differences among words that constitute, for Wittgenstein, a language game, but rather the qualitative differences between people who share a linguistic space, who try to make sense of and with each other. Language is social activity. Meaning is not derived from the relationships among words in the texts of the past, but by exchanging words in the present, in order to make something (socially) happen. In a recent interview Moi summarised her insights like this:

[writing is] action and expression. [We] need to think about what we stake ourselves… this will involve trusting our own experience, although our experience might at the same time need educating.

Student writing as expression and dialogue

According to Moi, then, experience is what education offers. New experiences, new ways of experiencing, and new opportunities to express and share experiences with others. So key elements of student writing are activity - doing things with words – and dialogue – engaging with others, using words.

My friend John Hilsdon is an academic writing specialist who works with students on the basis that academic writing is always doing something. His ‘functions of writing’ framework draws on theories of functional linguistics (that also owe a debt to Wittgenstein). But what matters to students is that by asking simple questions about the role of each piece of text, they start to worry less about word choice and ‘academic style’ and to focus more on communication. For example: how does academic writing produce credibility? It gathers and presents evidence, credits and values other people’s ideas, constructs arguments, reflects on experience, acknowledges situations and limitations, forms judgements. Credibility in writing is an active verb – in fact a whole Bloom’s taxonomy of verbs.

This contrasts with the credibility of synthetic text. Even when it isn’t making factual and interpretive errors, synthetic text can only borrow credibility as a style from the words and word orders in its lexicon. It is poor at making extended arguments, distinguishing good evidence from bad, or taking firm positions. In Ivanic’s sense of the term, it cannot be an author: it cannot have a purpose that is realised through the production of text. I have argued elsewhere that students benefit from accountable assignments that put the purpose of writing first. That taking responsibility for a position is an attribute of an embodied social person who can follow through on their commitments, whether in writing or in speech.

So then we come to dialogue. At the most basic level, talking about writing in class is an important way of mixing codes and discourses, expressing ideas in different registers, and ‘talking back’ at those authoritative writers of academic texts. Diverse varieties and registers of English as well as diverse viewpoints can be welcomed as legitimate resources. This is work that bell hooks spent much of her life doing and advocating for:

Embracing multiculturalism forces educators to focus on the issue of voice…To hear each other, to listen to each other, is an exercise in recognition. bell hooks (1994)

Many European higher education systems use oral assessments, and not only for PhD theses or for discursive subjects. For example, at the end of high school, the European Bacchaleureate requires an oral examination in three subjects, often including maths. In the UK, the idea of oral tests as a way of minimising the generative AI advantage has been derided as a step ‘back to the middle ages’, but it might just as well be seen as a step out into a broader culture of university learning as developing both written and oral communication skills.

‘Talking about writing together’ can become ‘writing about writing together’, live in class, on personal devices or on paper, on post-it notes and whiteboard screens, in shared digital documents and design boards. Again, there has been a reaction against the idea of dealing with generative AI by encouraging students to write live, as though this can only mean an invigilated live exam, heads down, no conferring. As a teacher of creative writing I have made many different uses of classroom time for writing. For some students the instruction ‘just to write’ is liberating. For others it is a chance to share and discuss strategies.

From bell hooks again:

Learning and talking together, we break with the notion that our experience of gaining knowledge is private, individualistic, and competitive.

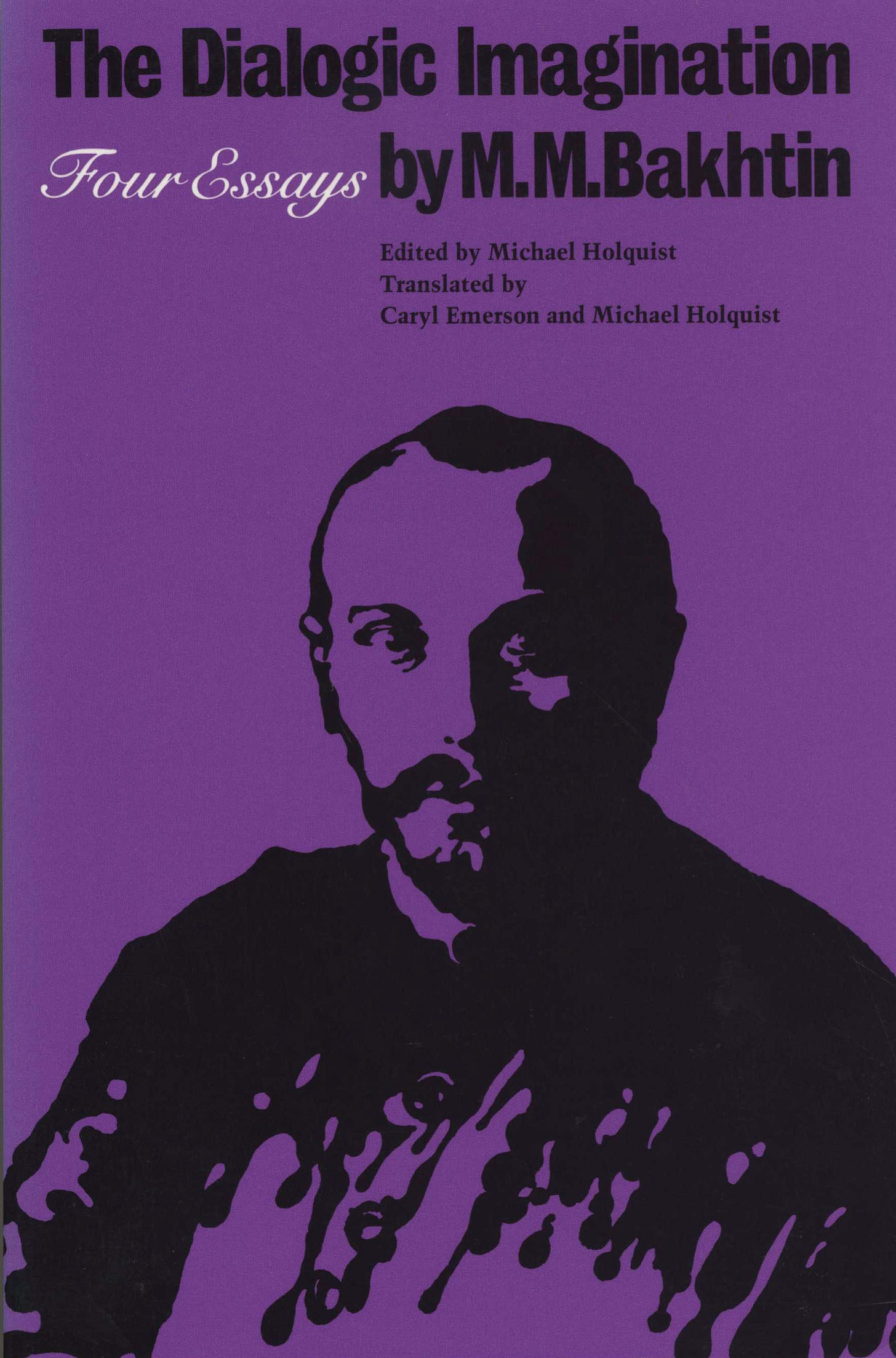

In breaking with this notion, I believe we come to see dialogue, beyond particular acts of talking/writing together, as part of the nature of writing. In the thinking of Mikhail Bakhtin, all writing is part of a ‘chain of communication’ in which meaning depends on who is being addressed, for what purposes, in what social setting. A piece of writing is never complete or self-contained, since it responds to earlier writings and genres of writing, and because it anticipates a response. Writing exists on a boundary between previous and future texts, self and other perspectives, private expression and public forms.

A focus on academic writing as talking back at someone or writing forward to make a difference can liberate students from a narrow focus on technique, and help them accept their writing as incomplete (imperfect) but engaged. I’ve encouraged this way of thinking myself by asking students to write a postcard or email to an academic author, to review and self-review academic writing (this can be in the style of a film or product review, if it helps students express their opinions more naturally), and by imagining ‘what happened next’ in response to a piece of academic or professional writing.

Bakhtin’s contribution to understanding student writing is explored in another great essay from the early 2000s, by Theresa Lillis: Student Writing as Academic Literacies: drawing on Bakhtin. She writes:

‘Bakhtin’s emphasis on the encounter between difference, on communication and knowledge making built on a dialogic both/and rather than a dialectic either/or, stands in sharp contrast to much academic meaning making. Dialogue within this frame is not just the process of meaning making, but is rather the goal: difference [must be] always kept in play.’

So while dialogue is a given, writing can always strive towards particular qualities of being in dialogue. And this is where I find another fascinating commentary on today’s language models. Bakhtin contrasted two modes of writing. One he called monological or monophonic writing, oriented on achieving authority within the text. The other he called dialogical or polyphonic writing, which acknowledges the diverse and contesting realities of alternate texts and voices. The engagement with other voices need not be a friendly one: parody, irony, pastiche, refutation are all examples of writing that allow another text/author to be heard but kept at a distance. Large language models are, on the face of it, rather good at repeating elements of a genre or style. But they have no sense of distance. They are unable to show, through markers of irony for example, different attitudes towards the style or genre or content that they reproduce. They are unable to bring alternative possibilities forward.

Here, I want to quote from an article on Bakhtin that I read in a rather obscure radical magazine Ceasefire. Published in 2011, it comfortably predates generative AI and so could not have been written in any sense against its logics. And yet I think its relevance is remarkable. I could not quite resist making my own dialogic annotations [in square brackets] on the original.

In monologism, one transcendental perspective or consciousness [the generative transormer model] integrates the entire field, and thus integrates all the signifying practices, ideologies, values and desires that are deemed [statistically] significant… Monologism is taken to close down the world it represents, by pretending to be the ultimate word.

In monologism, ‘truth’, constructed abstractly and systematically from the dominant perspective, is allowed to remove the rights of consciousness [the rights of original authors, especially from marginal perspectives]. Each subject’s ability to produce autonomous meaning is denied. Qualitative difference is rendered quantitative. This performs a kind of discursive ‘death’ of the other, who, as unheard and unrecognised, is in a state of non-being. The monological word ‘gravitates towards itself and its referential object’ [the model refers only to itself.]

We are back, here, with a similar critique of language models to the one I derived from Wittgenstein: that language is not representational form, however complex and inter-related, but action, interaction and expression, and in this:

There is no single meaning to be found in the world, but a vast multitude of contesting meanings. Truth is established by addressivity, engagement and commitment in a particular context.

Writing beyond passing

How can we bring these insights into support for student writing? How can we enable a variety of student ‘others’ to co-exist with the authoritative voice of the academy and its assessment practices? These are key questions generative AI poses to educators. And some of the answers may be quite simple.

We can support the same diversity and freedom of expression in academic writing that has traditionally been allowed in classroom talk and in non-academic genres of expression. We can invite students to make diverse commitments to telling it how it is, or how it seems to them. To express their experience in whatever media they choose – video, audio, graphics, presentations, code, multiple genres of text, including the popular and the marginalised. Being able to translate academic and professional concepts into different genres is something we can treat as a sign of a deep engagement, rather than a departure from the ‘norm’ of authorised expression.

This will mean coming up against students’ own aspirations to communicate in a privileged register. After all, it is not only universities that reward conformity to these codes. But students understand that the game has changed. Anyone with an internet connection can produce writing that ‘passes’ as undergraduate level work, at least to most readers. Recruitment practices are beginning to reflect employers’ understanding of this change too. Students will quickly see the value in developing a repertoire of means of expression, including some that do not pass through a synthetic editor or indeed through a screen at all.

We can also commit to forms of collaborative and dialogical writing, that universities always claim to value but almost never assess. One strange twist in the generative AI story has been a flowering of creative ideas for writing – role plays, parodies, peer review, annotation, self-explanation, argumentation mapping, writing for different audiences. The tragedy is that these ideas have all been put forward to support dialogue with a generative agent. How much better for student writing if this same ingenuity and playfulness was applied to supporting dialogue and collaboration in the writing classroom. This need not exclude generative agents, but it would prioritise the encounter with other students, who are at a similar stage of writing development to one another, and who have the same to gain (and to risk) from taking a more playful approach to their writing.

The expertise that resides in academic writing centres has never been more critical to universities than at the present time, and goes far beyond my own personal interest in the topic. I was able to tap into that expertise at the webinar, and I’ve summarised some of the participants’ suggestions for writing practice in the rest of this post. Even so, it can only be a limited and partial view of what is possible.

In the 'writing-to-learn' tradition, students are encouraged to write actively, collaboratively, and live in class. The idea of producing a finished text is let go. Instead, students write in short bursts, interspersed with peer conversation where active listening and mirroring are encouraged.

Several participants were using generative text in the context of highly scaffolded guidance. Students undertake separate activities such as: devise research questions, define terms, generate literature search criteria, summarise key texts, produce a research plan, develop a research instrument. Generative capabilities are then used to refine each stage. I welcome anything that makes the writing process less mysterious, more accessible, and available for reflection and review. As with my observations about dialogue, however, I have still to see evidence that a generative agent is offering more than an opportunity to reflect would offer, or (better) to engage with peers. There may be reasons why students find a generative agent more available and less challenging than other student writers – but this is a preference we might also challenge.

One webinar participant described giving students an essay question that they responded to in class with an outline. A copy was handed in as a first submission. Students then went away, did additional research, added references, and were able to use text generators to ‘get feedback and edit’ if they wanted to. The final submission included a reflection on what they had done and why. ‘It turned out that despite being able to use as much AI as they wanted, they absolutely could not do a good job unless they already had a good grasp of the basics of structure and argumentation and synthesis. If they used AI productively to enhance their own ideas they tended to do well.’

If students are to focus on the process of writing, assessment practice needs to change. So students might be invited to submit several drafts, or samples of writing in several stages (planning, reading-to-write, note-making, drafting, annotating). Students might also submit intermediate materials such as notes, annotated sources, concept maps, and responses to feedback. One participant described this as a ‘process-folio’; another as a ‘work book’.

Many suggestions involved making writing ‘live’ and ‘in person’, or at least engaging in live talk about writing. When these approaches were first suggested as a means of countering ‘AI cheating’, there was a fairly hostile reaction. Wasn’t this a step back into the medieval age? If by ‘live writing’ you think only of a traditional, closed-book, invigilated examination, and if by ‘talking about writing’ you think only of a formal viva, it’s easy to see these as backward steps both for equity and for the diversity of ways students have come to be assessed. But low- or zero-stakes live writing is entirely different. It can integrate writing more easily and naturally into other forms of expression (talking, note-making, doodling). Talking about writing brings this often intensely private activity into the light of day, and into the zone of proximal development, where students can be exposed to different strategies and possibilities beyond those they would naturally reach for themselves.

After all, aspects of university learning that involve live practice or performance, such as lab and field work, professional and creative practice, are often highly motivating for students and they engage different pedagogies on the part of teachers too. In my own teaching practice (founded in creative writing) I have encouraged students to treat academic writing as a foreign language, to parody it, to ‘write on from’ a particular academic paper or chapter as a form of fan fiction, to engineer a paragraph as a machine with moving parts, to cut and paste with literal scissors and glue. (A recent workshop that I ran with three colleagues, ‘generative alternatives’, explored these and other creative possibilities.)

Other suggestions in the webinar offered a twist on the classic Turing set-up: invite students into the ‘judge’s position, and ask them how well synthetic text ‘passes’ as good student writing. This calls for both critical engagement and a sense of agency. Both are possible, I think, if students have some understanding of the subject matter and of writing practice. However, as soon as students leave the classroom where this agency is being offered, and where the position of judge is being held for them, they are likely to slip back to the more familiar side of the table.

The authority vested in academics as assessors is real. And the messages pushed at students by the AI industry are all about academics as enemies of ‘passing’, implacable judges, interested only in catching students out. So while I think this critical move is essential, I’m not sure it’s sufficient without ongoing support for judgement as part of the process of writing, as something students are entitled to do already but that teaching can actively support (remember Moi’s ‘experience might at the same time need educating’?)

The webinar also provided an opportunity for debate on how universities are responding to the challenge of generative AI. Many participants noted that departments were giving students very different guidance, ‘which recognises the complexity of the technology and how it relates to different subjects, but can be really confusing for students (especially on joint degrees)’.

The conversation touched on theories of language: ‘we are emphasising to students (in some disciplines anyway) just what Helen has been talking about—learning and self-expression through writing’; ‘might it all come down not in the register of language used but in the ability of the author to express and indicate stance and criticality?’ Participants debated to what extent Ivanic’s idea of ‘authorship’ (‘the ability of the author to express and indicate stance’; ‘organisation of ideas’, ‘reasoning’) can be separated from her idea of ‘discourse’ (‘vocabulary and grammar’, ‘accuracy of expression’). While this question was not resolved, all agreed that the register students speak and write in makes a difference to their perceived credibility as authors, and that this is a connection no academic exercise or course of study can entirely break. The reality is that: ‘Global Englishes are not accepted as “passing” yet.’

There were, not surprisingly, contrasting views on how students experience generative AI. Some reported that students are anxious not to use or to overuse it: ‘because it takes away their power of thinking’; ‘it completely erases the writer's voice, the writer's “accent”’. ‘Perhaps it’s about getting students to think about what will be effaced or muted (their critical voice, their intellectual identity) if they ask a chatbot to impersonate them.’

Others felt that students benefited from access to a more ‘formal’ voice for expressing themselves. ‘AI opens up so many new multimodal writing processes, I wish I had time to get my students to experiment with them all’. ‘AI makes them start off a step further, since structure/grammar and the lot are given. They need to delve deeper and attempt criticality much earlier in their careers as academic writers’.

But there was consensus, finally, on the need to support writing beyond ‘passing’, recognising that the main losers from a transactional approach are students themselves. Academic writing can provide opportunities to develop their thinking, to find out what they think, to engage in thoughtful dialogue with people and texts, and to know themselves as different to who they thought they were. These are all more possible when assignments are oriented towards dialogue and expression, as Toril Moi defines them, and when, as bell hooks demands, writing classrooms are spaces ‘to hear each other, to listen to each other… an exercise in recognition’. By which we have to mean something more profound than an exercise in identifying who passes as (the right kind of human), and who fails.

This is such an important article - thank you Helen. The strategies recommended for assessment reform in my country are firmly set at the course wide, or programmatic level. This offers opportunities to rethink how/why/what we assess. And the focus is also on the process of learning. As I step in to collaborate with my colleagues in a large humanities course, I will be bringing the ideas in this article with me.

So with tools like LLM's, teaching and learning become necessarily social and gravitate towards social (oral) construction of meaning?