Life is imperfect

Starting this week: tl:drs, updates and quick takes for when the long reads are too long

News

A bit of personal news: this week i turned down an invitation to keynote a respected ed tech conference. The conference committee approached my concerns respectfully and I don’t want to embarrass them, but I’d like to embarrass the main sponsor, Proctorio, who are the reason I will be staying at home.

Proctorio are not unique in their oppressive surveillance of students (the link is to an oped piece in Teen Vogue, one of my favourite critical journals). But they have made a name for being aggressively litigious against anyone, however minor their role, who speaks up about the negative impacts of their technologies. This makes them a uniquely inappropriate sponsor for an academic conference where speaking openly and critically is supposed to be the point. It’s been good to learn from my networks that I am not alone - people with far more prestige have turned down conferences because of Proctorio’s sponsorship.

Edtech criticism does confine itself to the margins if we don’t engage with the messy world of practice, and (therefore) the commercial products and the everyday decisions about them that shape practice. But the always-uneasy relationship between commerce, educational practice and critique has recently become a rift, and that is because of the aggressive actions of companies like Proctorio. I think the message to conference committees is this: if you want to field a balanced group of speakers, including critical voices, you need to address imbalances of power. And you can’t do that under the banner of a company well known for pursuing their critics through the courts, to the destruction of their careers. What they are advertising on your podium and at your drinks reception is the deep pockets that allow them to do that.

Much more happily, last week I recorded a ‘10 minute chat’ about Generative AI with Tim Fawns at Monash University. No sponsors, no drinks reception, but he was the perfect host. I’ll post a link when it’s public, but meanwhile there are plenty of other interesting ppl in the series, most recently Anne-Marie Scott, whose blog covers all things open education and technology, and who has fascinating things to say about AI and decision making in education.

tl:dr

This week’s tl:dr is for ‘Luckily we love tedious work’, an essay length piece on graduate employment and the rush for an ‘AI ready’ curriculum. Here’s the short version.

Big tech companies are also venture capitalists: use cases are produced downstream of investment$$$

“Hype is as much a part of the new technosocial structure as the nvidia chips it runs on”

Universities are creating use cases for generative AI, particularly in the rush to an ‘AI ready’ curriculum. Is this a good thing for graduates?

However, businesses themselves are not as enthusiastic about the new tech as the hype would lead us to believe

Generative models themselves are restructuring labour - including graduate labour - in their image

The ‘world of work’ beyond the GenAI stack is using technologies like GenAI to restructure work in ways that make it more, not less, routine; also more precarious and less meaningful

Fear of ‘losing your job to AI’ is just one reason workers accept this kind of restructuring; narratives around the need for all graduates to be ‘AI-ready’ really do help to reshape graduate work

Getting under the bonnet of the only two use cases we have for generative AI at this time: content at scale, and natural language interfaces on technical work

Content at scale only ramps up the productivity demands on existing producers, makes attention scarcer, and further devalues our knowledge ecosystem

Natural language interfaces make technical work such as coding and data analysis more fun, more productive, and available to less skilled workers, but at a cost of future expertise - and again without making technical work any better paid, more secure, or more interesting in the long run

A three-way critique of the idea of ‘artificial general intelligence’. There will be plenty more of this in long reads to come, but for now you can enjoy:

a bit of robot parcour, ‘fully functional female’ gynoids, and why all this shows up the folly of ‘general’ robotics

the origins of the ‘g’ factor or idea of general intelligence in the work of Spearman, its critics, and its less-than-happy history in eugenics and psychometric testing

genuinely valuable applications of what is called ‘AI’ are narrowly scoped and used in specialised workflows involving expert people and other tools (that are not usually described as ‘intelligent’ such as microscopes, scanners and lab processes)

An appreciation of the call for ‘human skills’ in the university curriculum, especially if it means universities stop defenestrating humanities departments, but…

A warning about naive, romantic ideas of ‘humanity’, setting the ‘human’ against the ‘technical’. There’s at least one long essay on this in draft, so hold on for some humanist/post-humanist/post-post-humanist, trans-humanist and new humanist fun while (hopefully) enjoying the preview

Meanwhile a call to prioritise the crises facing embodied life on a finite planet - the curriculum as a space to address these and not a space defined by the inverse of what this year’s most hyped products are supposed to do

There are big questions about who will fund the meaningful jobs, but we do know that bullshit jobs are bad for mental health and bad for all our futures, so let’s design with hopeful futures in mind and alongside students who can see through the bullshit

‘If AI can do your job, you deserve a better job’

Notes and boosts

I was feeling super ‘sharp’ last week when John Naughton of the Observer and Open University gave imperfect offerings this recommendation:

John’s indispensable (and incredibly prolific) writings on all things tech are brought together on his substack Memex 1.0.

Gary Marcus continues to drive fast in the other direction to received opinion on his ‘Road to AI we can Trust’ blog - I do wonder if he needs a rebrand at some point (the road to nowhere perhaps?). I referenced his Rise and fall of ChatGPT post in my last essay, but three other recent posts - on the economics of AI, the ‘enshittification’ of our knowledge ecology, and threats to democracy - are also must-reads.

There has been discussion about setting up an AI special interest group on the Learning Developers in HE Network - a forum I have always found deeply thoughtful and in touch with the student experience. I’ll be joining this group, initiated by Kate Coulson, and I look forward to finding out more.

I’m also following a discussion on Alan Levine’s Open Education Global list, that has been unpacking Paul Stacey’s long post AI from an Open Perspective and has arrived at the part about learning. Stacey asks:

What are AI machine learning, deep learning and neural networks?

What are the learning theories, models and practices being used to train AI?

He goes on to identify ‘AI learning’ as ‘behaviourist’, which he says ‘limits the usefulness of AI in terms of engaging learners intellectually, physically, culturally, emotionally and socially’. I see where he is going with this idea, but I also think it is a mistake to talk about ‘learning’ in these two questions, the one about ‘machine' learning’ and the one about people learning, as though it is the same thing. I’ve written incidentally about learning theory in my posts on Language models and on Artificial (General) Intelligence but I am keen to make this the focus of a new post - and to see where the OEG community goes with these questions too.

On his Digital Education Practices site, Dustin Hosseini reports the results of some experiments with text-to-image generation using DALL-E. He warns that ‘some readers will find the results disturbing, upsetting and potentially angering’ and goes on to show how they reproduce ‘deeply ingrained cultural prejudices’ around gender, race and national origins. This is work of the kind we need: practical and theoretical, angry but evidence based. In Hosseini’s version of AI literacy, the focus is ‘understanding where sites of coloniality replicate harmful generative AI algorithms’ - not easy, but surely necessary.

Elsewhere, Peter Schoppert keeps plugging away at the issue of generative AI and copyright. This week he reports on the take-down of a public version of Books3, a dataset known to be part of the training data used to build the foundational models. From a copyright perspective, the take-down was clearly justified. But as the original engineer of Books3 points out, without public access to this data, no-one will be able to understand and evaluate the performance of the models based on it. It’s a slightly rickety argument for openness, but it does illustrate how new epistemic technologies produce new challenges and trade-offs for the open agenda.

An upcoming NY Times lawsuit aims to settle the question of copyright in training data thus: by establishing a right to payment for every use of its content, NYT could force OpenAI to ‘wipe ChatGPT and start over’. More likely - and more interesting, I think - it that this case represents a fork in the road for OpenAI’s downstream use cases and therefore its business model. NYT was apparently in negotiations with OpenAI to broker a deal along the lines they recently reached with AP - that is, to provide users with a ChatGPT style front end on AP’s extensive news archive. NYT seems to have got cold feet, realising that a service of this kind could put out of business the very news-gathering enterprise it was based on. Even for major news organisations that could gain first mover advantage from this kind of deal, it’s obviously a close-run calculation.

The energy with which OpenAI is chasing potential partners suggests that it has learned from the infamously leaked ‘we have no moat’ document. Not enough people are going to pay for its content-hose. It needs to market its chat functionality - its natural language interface - to existing owners of high quality content. Or ‘partner’ with them: even better. But with so many small and medium scale models being built out, it may be difficult to persuade content owners that they need such a partnership, when they can pay some bushy-tailed start-up to build them their own front end. NYT will have realised, however, that this path only leads to the sunny uplands of content monetisation if their content is not already part of the training data in the foundation models. They also need their moat. (Basically, it’s castles all over.)

At a recent conference I asked why universities are not taking a similar approach, building their own front ends on academic content - their own ivory castles if you like. I was told by the expert speaker that this was too expensive, and that partnering directly with one of the big players was the only option. The divergent AP/NYTimes approach may give universities the chance to see how this plays out in an analogous sector.

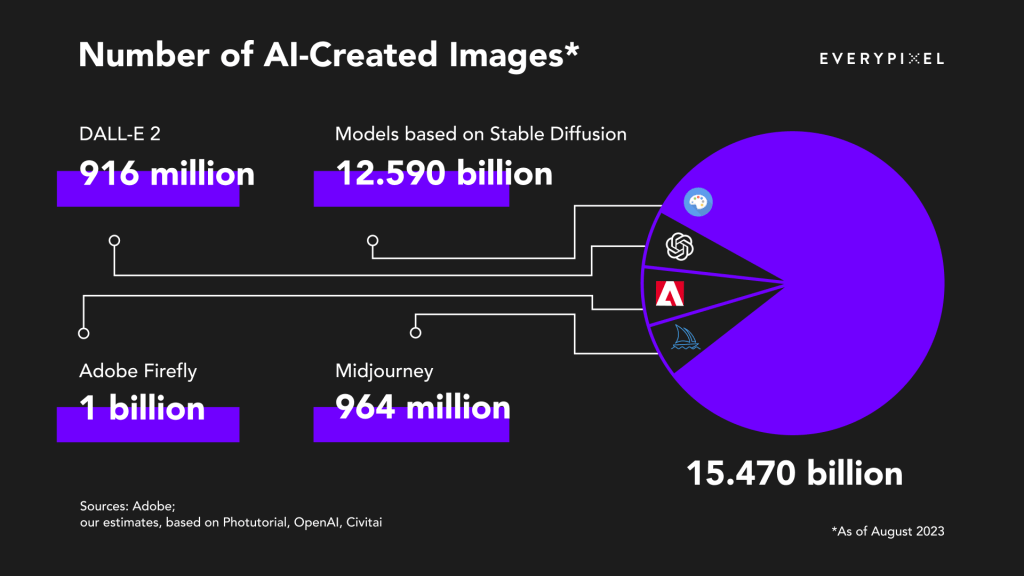

Finally, a few clicks from the Peter Schoppert post, I found this infographic showing that the number of AI-produced images as of August 2023 equals the number of photographs taken in the first 150 years of photography (probably).

Since those first 150 years do not include the mass production techniques of digital photography and post-production, or the mobile phone era, the volume figure doesn’t surprise me. What it does make me think about, though, is the amount of time and the quality of attention paid to those early photographic images - both the making of them and the ‘reading’ of them - and the poverty of attention we have for images today. Susan Sontag’s famous essay On Photography (written in the 1960s) complained that the ease of image-making through photography had stripped events of their meaning, leaving people in a "chronic voyeuristic relation” to the world. What would she make, I wonder, of the mindless auto-mimesis of Stable Diffusion and the like, that removes the viewer still further from the event and their relationship to it? That removes us from image-making as - minimally - an act of conscious framing and attention, to bob in a sea of visual riffs and memes, of pastiche and montage, adrift from all anchor points?

Thanks for standing up (well, metaphorically, as you won't be behind the lectern).

And great that quality is recognised by the excellent John Naughton.

On holiday otherwise I'd write more!