Marking the Government's homework on public sector AI

The Government's plans for automated marking and autonomous missiles, and making public data 'safe' by selling it to private 'security' businesses

It’s marking season and my heart sinks as I turn to the all-boys group project that is the Government’s AI Action Plan. Despite the feedback I gave them earlier in the term about poor planning and a lack of research, they have ploughed on with the bravado that only ignorance and testosterone can supply. And it does seem to be in full supply.

Back then I suggested that tax breaks and deregulation for building data centres was not enough to procure ‘sovereignty’ in AI governance, and that ripping up laws protecting the UK’s creative industries - a real source of value and prestige - would not boost UK productivity. Similar feedback has now come from higher places. The UKAI trade body agrees that the Action Plan - written and led by major AI investor Matt Clifford, informed by the Larry-Ellison-funded Tony Blair Institute, and stewarded by Peter Kyle (with ChatGPT for policy advice) - does not strengthen the position of UK companies globally. Nor does it, according to the wonderful Beeban Kidron, protect UK citizens from the predatory intentions of global AI corporations.

The big bet – that AI can produce ‘efficiencies’ in public services while cutting costs – is looking worse and worse. The Netherlands is four or five years ahead of the UK in developing public sector AI, and (unlike the UK) has put ‘responsibility’, ‘fairness’ and public accountability at the heart of its project. But after a series of AI related scandals, including tens of thousands of families accused of benefits fraud, flagship projects have been dropped. Research from the Ada Lovelace Institute involving 16000 members of the UK public found low levels of trust in AI for services impacting their lives, and that poor governance has ‘the potential to damage people’s trust and comfort in the use of technology in the public sector, and even to undermine the perceived legitimacy of services and of the behaviour of government itself’.

But Starmer’s Government is not interested in what the public thinks of its behaviour or in learning from actual public sector projects. It is running with the big boys’ gang. Last year the CEO of Microsoft UK was appointed by Starmer to lead his Industrial Strategy and within a week the Government had signed a 5 year deal with MS, locking it into Microsoft cloud services. A couple of months later the Chair of the Competitions and Marketing Authority (CMA) was forced out by ministers and replaced by the former CEO of Amazon UK, and 100 staff were sacked. Odd timing, just the new ‘Digital Markets, Competition and Consumers’ act was about to come into effect and in the middle of CMA investigations into the conduct of Microsoft, Apple, AWS and Google. You’d think they’d need all the staff they could get. Luckily, the new Industrial Strategy (January) included a major ‘reset’ for the CMA requiring it to be resolutely ‘pro-growth’ and ‘pro-investment’ and to interpret its brief of defending UK consumers ‘flexibly and proportionately’. So the former CEO of MS in the UK is advising the former CEO of Google in the UK not to regulate big tech in the UK, and this is what we call the public interest.

According to its two latest Memoranda of Understanding - a cute name for a declining world power signing its assets over to the new ones - Google will upskill public sector workers with ‘a new Google Cloud training programme’, while moving public sector systems over to ‘Google Cloud technology’. And OpenAI will ‘develop sovereign solutions to the UK’s hardest problems, including in areas such as justice, defence and security, and education technology’.

Remember these priorities: justice, defence, security, and education technology. I feel sure we will be seeing them again.

TL:DR

The dubious sovereignty of ‘sovereign compute’

There is no ‘sovereignty’ to be had from getting as close as possible to big US tech. There are other ways of developing public infrastructure in the public interest, if they are allocated and governed accountably.

Supercomputers and startups

Hyperscale data centres are not ‘supercomputers’ and there is no real evidence that they support local prosperity. In fact, around the world, communities are organising to resist them.Jobs, jobs, jobs, and Amodei’s dream

I look at the evidence for - and against - a jobs bonanza from ‘AI’ in the UK, and interpret Amodei’s dreamSkills on a shoestring

‘Mainling AI into the veins’ of education for £8 a shot, and the first of several appearances for the UK Spy AgencyHomework marking - again

The magic marker-bot and the highly educational careers of Michael Gove and Dominic CummingsWho should be safe?

The militarisation of the nation state, spooks again, and why AI security and AI safety are not the same

The dubious sovereignty of ‘sovereign compute’

Data centres are at the heart of the Action Plan for AI. Removing planning constraints and clamping down on protests will make it easier for US companies to park their polluting, power-grabbing, water-guzzling data centres on UK soil. When I compared this with a former policy of parking US cruise missiles here I thought it might have been an analogy too far, but it has since emerged that as well as data centres the UK will host US ‘tactical’ nuclear missiles at RAF bases for the first time in 20 years, at a time when hosting US missiles is working out really quite poorly for other countries that happen to be closer than the US to its various theatres of foreign intervention. Last week’s fanciful metaphor is this week’s headline, and the only thing more depressing is the failure of proper paid journalists to look into it any further.

Even if you doubt Ed Zitron’s figures, there is no question that a huge swathe of the US economy is currently floating on Nvidia chips and nothing else. Nvidia is where the froth and promise of AI turns into material infrastructure: chips and cloud (i.e. data centres) are the only parts of the AI stack that are seeing any profits. All the big five are losing on AI and would be losing bigger if they did not have access to compute at privileged prices (these companies, with Nvidia, make up over 30% of the US stock market - and growth is down for all of them). Now, helping the US economy to stay afloat on its AI bubble may be considered good economic sense, since when the sky falls in on the US economy everyone suffers. But that’s what buying Nvidia chips is doing.

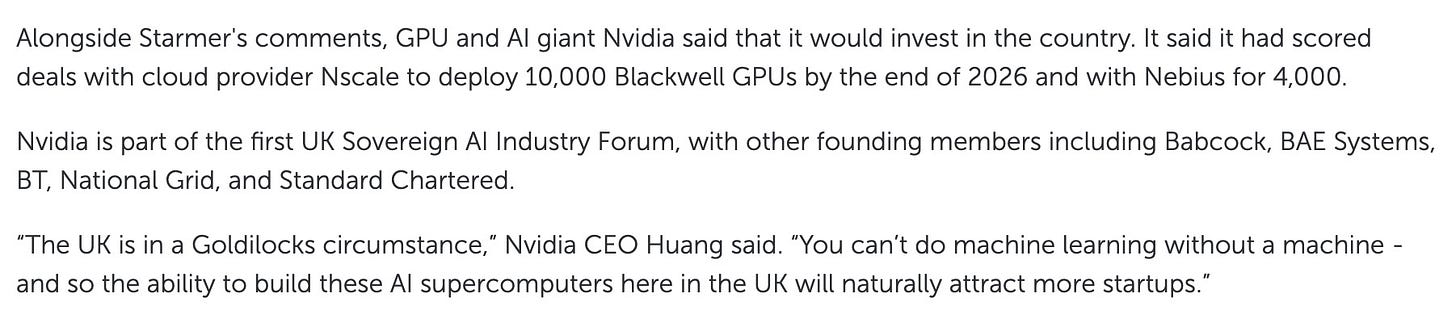

The UK’s first ‘Sovereign AI Forum’ hosted by resolute nationalists (that is, US nationalists) Nvidia, claimed ‘founding members’ Babcock, BAE Systems, BT, National Grid and Standard Chartered.

The first two of these are weapons manufacturers, reinforcing the impression that when the Starmer government says ‘public’ and ‘AI’ it is really thinking militarisation and national security. A trawl of all five UK business web sites finds no mention of the ‘sovereign compute’ initiative, and the promise of £1billion in public spending, comes with no details of when and where. The new partnership with OpenAI (July 2024) – presumably part of the same initiative - is similarly short on specifics.

However, we do know a bit about Nvidia’s plans for the UK

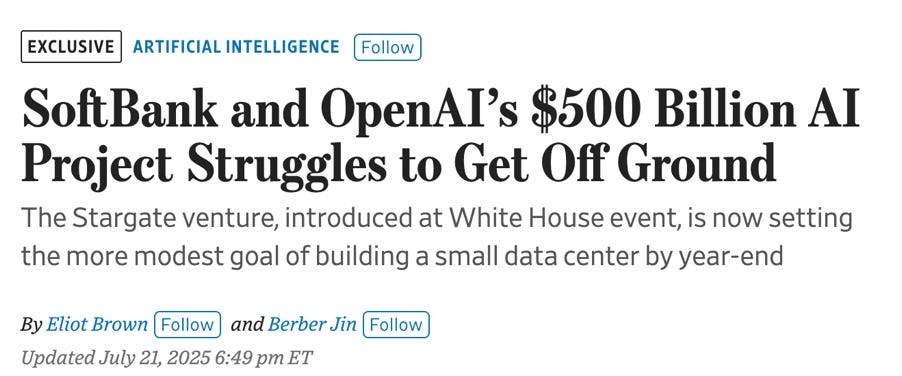

I’m not sure Jensen Huang was fully briefed on the Goldilocks story, but the time is always ‘just right’ to buy Nvidia. The company that by some estimates has 98% of the global market in AI GPUs, and provides the only AI-specialist hyperscale solutions, is certainly desperate for more places to build data centres. Local communities are resisting them across the US and in South America, and attempts by the Trump administration to prevent states enacting their own guardrails have temporarily stalled. Building data centres is hugely complex and expensive: even the US government/OpenAI $500billion Stargate project has been scaled back to building just one in its first year.

And so Huang has been traveling the world talking up the need for governments to invest in ‘national’ or ‘sovereign’ compute, since few other buyers can take on the kind of debt involved. Hyperscalers or ‘bit barns’ make extrarordinary demands on power and water supplies, as well as network infrastructure, and these must be uninterrupted, even if that means depriving local populations of resources. So bit barns can only be built where local, regional and national governments are on board, tax regimes and planning laws have been made favourable, infrastructure is in place or can rapidly be improved, and suppliers of power, water and bandwidth are all signed up to the new priorities. (Just wondering: has anyone looked into the state of the UK water industry recently?). Hyperscale certainly demands sovereignty - control over planning, services and infrastructure, and the policing of local communities. But it’s not so clear what sovereignty it is giving back.

The macho and frankly imperialist demand for the UK to be an ‘AI maker, not a taker’ ignores that supply chain for compute is complex and globalised, with most of it firmly anchored in the US (or China). While Nscale seems to be the front face of UK ‘sovereignty’, the bit barn boom is actually being driven by four massive US hyperscalers, CyrusOne, CloudHQ, ServiceNow and CoreWeave. NScale, the company that is supposed to supply the first tranche of ‘sovereignty’, only launched in May last year. It announced in January that it had secured a site in Loughton, Essex, ‘that can house up to 45,000 of the latest Nvidia GB200 GPUs’, and will go live with 50MW of capacity by the end of 2026. You’ll notice that NVidia is only allocating Nscale 10,000 GPUs and not the 25k that would be needed to meet this capacity. (If further proof is needed that Nvidia is the real sovereign here, how many industries can ‘allocate’ their product based on their control of supply? Oil and gas maybe?).

In fact Huang seems to regard the UK as a very minor courtier, skipping off smartly from the UK launch to Paris where France is allocated more Nvidia GPUs in the next year than the UK’s infrastructure project overall. But then, France is investing 100 times as much public money in compute (109 billion euros). Because the only serious alternative to the US and/or China AI stack is the one Europe is (sort of) trying to build, at least on common market, common regulatory terms. And if the UK were willing to throw some weight behind that effort it might be a little more possible. But for ‘sovereign’ investment, nothing Europe can invest can match what is being put up by the gulf monarchies, the ones that pack the real ‘sovereignty’ when it comes to wealth and hardware. UAE has just brought 100k Nvidia chips online and plans to import 500k every year, while Saudi has struck deals worth $600bn with Nvidia, AMD and AWS. These are the market ‘makers’ that the US takes seriously as partners.

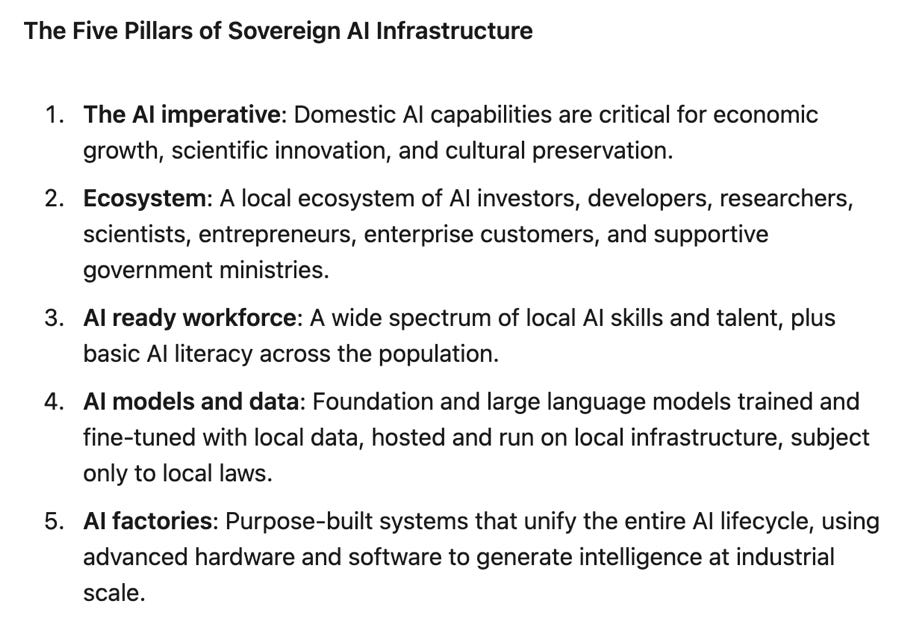

Perhaps to discourage close reading of the AI geopolitical power map, the definition of ‘sovereignty’ in relation to UK data centres is vague. And so we must look to Nvidia for help:

Here’s my reading.

1. This is Nvidia’s version of OpenAI/Stargate’s controversial ‘AI for Countries’ initiative, ‘supporting’ nations to build AI infrastructure that will remain under US control. In return for chips, countries must ‘invest in expanding the global Stargate Project—and thus in continued US-led AI leadership’. OpenAI unblushingly uses the cultural biases and misalignment of its models as a reason for countries to plug in their own cultural data. In return for being part of the ‘AI for democracy’ empire, countries will hand over control of critical national infrastructure, vaults of cultural and biometric data, their most promising researchers and a chunk of sovereign wealth. Our friends the Tony Blair Institute were out in front at the AI for Countries launch, ready with their own blueprint for sovereign AI: ‘countries that have the strongest relationships with large technology providers will be best placed to provide effective public and private computing infrastructure’. And that is democracy. Talking of strong relationships, did I mention that the new head of public policy for Nvidia in the UK is fresh from directing the TBI?

2. An interesting list of key players, but whether the ‘developers, researchers, scientists’ who are actually building AI are doing so for public projects or private profit depends entirely how ‘AI investors’ are constrained by the ‘government’ to allocate resources. At the moment all the power, compute and data are on the first side of that relationship. How could ‘government ministries’ take a more engaged role than waving little union flags from the ‘supportive’ sidelines? There’s plenty they might try. The UN has a well established list of principles for the development and risk-management of Digital Public Infrastructure, and there are serious attempts in Europe to articulate - beyond regulation - what public interest compute could look like (though, whoops, again the UK seems to have opted out.)

3. Given the brain drain, and the need AI has for ‘basically literate’ workers in its data engines, training is a public cost and an AI industry benefit. More on skills in the next section.

4. Once built, the infrastructure will be owned by the hyperscale company and their creditors. How will access for UK users be allocated, and on what terms? Unless this question can be answered with real savings for publicly beneficial projects, most users - who do not have fibre optic connections to a specialised supercomputer in their back garden - would be better served by having better broadband infrastructure (the UK ranks 43rd in the world) so they could access cloud services wherever they happen to be located. ‘Local laws’ could tip the balance of infrastructure development towards the public interest, but the AI industry is leaning heavily on governments to deregulate as the price of compute, and as we have seen, the UK Government has shown itself exquisitely sensitive to such pressure.

5. AI factories is how Nvidia chooses to characterise its vertically integrated stack, extending its monopoly power all the way from GPUs down into minerals and rare earths, and up into local energy plants and water supplies. Comparing the scale of ambition with the development of the factory system is honest at least. As I have always argued, AI is not a ‘tool’ it is a system for restructuring labour, and it’s increasingly obvious that means restructuring the whole of social and economic and planetary life as well. Perhaps Jensen thinks the factory metaphor will go down well in the birthplace of the dark satanic mill, it’s just that historically the UK ruling class has been building the factories and exporting their ‘externalities’ to the rest of the world, and not the other way around.

So how could the UK Government secure capacity that is owned, used and governed in the public interest? First, recognise that very idea of ‘sovereignty’ in compute is a chimera. At least European nations understand they can only do this as a bloc. The brilliant Cecila Rikap argues that South America has a chance if its governments can work together, but that it is slipping away. For nations without the UK’s post-imperial resources, or power bloc solidarity, the choices are even more stark.

Second, recognise that the interests of democracy may not be served by ramping up the data and surveillance capacities of the nation state. Not only are nakedly autocratic parties increasingly able to seize state capacities - something the UK is far from immune to - but the tech giants that provide these capacities are actively fuelling antidemocratic forces, as they increasingly find democracy an annoying drag on their ambitions.

Instead of a spurious ‘sovereignty’, suppose the aim was to procure and secure a digital public infrastructure, composed of material elements (cloud compute, networks, data) and governance arrangements that would prioritise the needs of diverse interest groups. These might be local, regional, sectoral (voluntary, third sector, health, education, research), but the priority would be the participation of those least served and most at risk from the current commercial infrastructures of AI. If I could set some homework for Peter Kyle, it would be these two recent papers, Digital Public Infrastructure and public value (Muzzacato et al. 2024) and the White Paper on Digital Sovereignty, (Rikap et al. 2024) both from international research teams working in the UK. Muzzacato’s Common Good Framework offers five principles for securing public agency in relation to infrastructure:

purpose and directionality;

co-creation and participation;

collective learning and knowledge-sharing;

access for all and reward-sharing;

transparency and accountability.

And the White paper suggests how these might be applied in specific policy proposals for public compute. (This is my paraphrase of the original – but please go and read it!)

1. A democratically accountable, publicly-governed digital stack, comprising digital infrastructure as a service, platforms, a public marketplace without lock-ins, and state procurement preferentially from this marketplace.

2. A research agenda focused on digital developments that could solve collective problems and enhance human capacities, with public research agencies funded to counterbalance the expertise in commercial labs.

3. ‘Ecological internationalism as the basis for national digital sovereignty’, minimising the resources needed and the environmental impact (we could add ‘frugal compute’ or system-wide sustainability as a sixth principle to Muzzacato’s).

4. Dismantle state surveillance and regulate against the ‘misappropriation of collective solutions by specific governments’.

Whatever the future of AI, there is a need for public control of public infrastructure. But this isn’t it.

Supercomputers and start-ups

This whole deal with the devil is supposed to be in the interests of economic growth. Remember, Huang has said that ‘supercomputers in the UK will naturally attract more start-ups’.

So there are two things to point out here. First, supercomputers sound, well, super, but they are not the same as data centres. Supercomputing infrastructure is highly integrated on a single site for specialised data operations, such as advanced research. Data centres are racks of GPUs connected to the cloud for whoever can afford to burn them. While some of the networking technologies are converging, the deployment models and network requirements are quite different.

There is a strand of the Action Plan that does concern supercomputing. The UK AI Research Resource promises to multiply available research computing for AI ‘by twenty times’. So far the £750million announced for a new supercomputer at the University of Edinburgh does not quite replace what the previous government had already allocated to this project and that the Starmer government put on hold when it took office. So this is not a promising start.

Whatever the finances available, the AI Research Resource could set a precedent for public oversight over the allocation of supercomputing resources and the projects that run on them. The Ada Lovelace team (again) suggests that this could mean ‘board seats and mandatory public engagement exercises’ for those most impacted by AI. Priority could go to those researchers and research topics that do not have access to corporate funding, which is likely to mean topics that do not centre the interests of the AI industry (sustainability, safety, risks and harms for example). We must wait to see whether ‘breaking the mold of traditional academic-led software projects, and ‘a stronger role for industry’ will indeed involve public representation and public interest projects, but it isn’t a great sign that DIST is effectively asking the data centre industry to tell them how to build it.

All that being said, the proportion of sovereign compute allocated to supercomputing is small. So can data centres also ‘attract’ innovation and prosperity, as Huang claims? Sunny predictions on this issue spilled from a Public First report that was shared by Nvidia at the launch of the AI infrastructure strategy, luckily being published on exactly the day the public might be asking questions:

The report does not link to any actual research, only back to the Nvidia press release about it, but it does include some tantalising details of PF’s methodology. Skip ahead if you can’t be bothered with the working out.

THE WORKING-OUT So the key figure in PF’s calculation of added value is something they call the ‘Computer Access Metric’, calculated using an impressive sounding ‘Gravity model approach considering data centre capacity and inverse square distance’. I contacted an expert in planning who told me that the gravity model is indeed used to calculate access to services such as healthcare, where capacity and distance obviously matter. But why does distance matter when it comes to accessing cloud compute? The speed and quality of networks are what really count here. And if PF did include some measure of network quality, either in ‘capacity’ or in its measure of ‘distance’, it’s not clear how network quality translates into local economic benefits - not unless all your users have their own fibre optic link-up. The expert told me that the methodology was, at best, unclear.

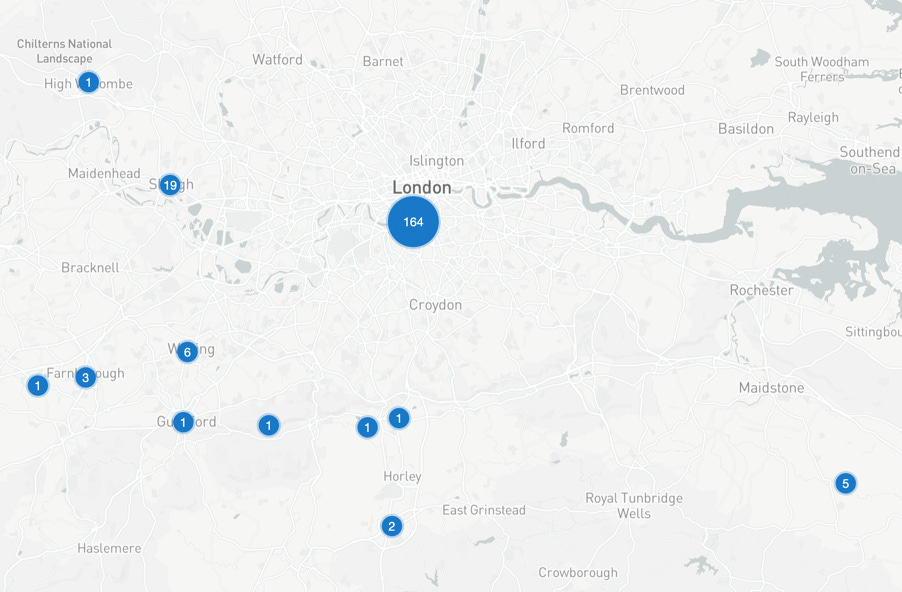

There is one application of computing, however, where distance matters at a local level, and that is high frequency/low latency stock trading. In the finance sector, miliseconds make the difference between gaining and losing a trade, which is why trading platforms are typically integrated with data servers on site, using fibre optic cables and microwaves to achieve ‘ultra-low latency’ in transmission. It’s also why so many UK data centres are in the City of London.

Surely it can’t be that the figure PF has used for the local benefits of data centre construction includes all those data centres in the heart of the UK’s financial services sector, one of the country’s very few growth sectors, and one of the very few places where co-location of data centres with operations really does translate into economic benefits?

THE ANSWER (did you skip here?) The benefits of a data centre nextdoor to a financial trading platform in the City – or indeed a supercomputer cluster in a research park in Oxford or Edinburgh - are unlikely to be replicated near a bit barn in Loughton, or scaled up from there to the UK as a giant bit barn farm in the North Atlantic. So let’s hope this is not how the calculation was done.

Because trashing the UK’s climate targets and planning protections really does require some benefits on the other side of the scale. Given the huge impact of data centres on the National Grid, scarce water resources and natural environments, their minimal job creation, and the rising tide of protest against them, surely they should only be built after extensive auditing of the environmental impacts, where local communities agree that the benefits outweigh the costs, and within a democratic framework that has public service and public science contractually locked in.

Instead, public representatives who try to block data centres are kicked out of the way, and members of the public who want a say over what gets built with public resources are more likely to be criminalised than invited to join the board.

Jobs, jobs, jobs, and Amodei’s dream

So you’ve heard me say elsewhere that there are no signs as yet of the promised productivity bonanza from generative AI. Workers are being asked to work faster, do more with less, accept deskilling and casualisation, to use AI rather than enlist the help of a junior colleague, but it’s not clear that any of this is improving the quality or the productivity of work.

But how about in the AI industry itself? Isn’t there a jobs boom there to be ‘unleashed’?

CloudHQ’s £2 billion hyperscale campus in Didcot, Oxfordshire promises 100 permanent jobs. The data centre at Loughton promises 250, though it’s worth noting that such projections have proved wildly optimistic in past projects. Even if these numbers are in the right ballpark, that’s not a lot of jobs. In general, tech companies tend to have few employees per unit of capital, and data centres are among the most capital intensive of all tech projects. They are called ‘bit barns’ for a reason. If you own a data centre you aren’t exploiting workers you’re extracting value from a pile of computer chips running night and day. Anthropic’s CEO, Dario Amodei, shared a dream of ‘$1bn companies with just one employee’.

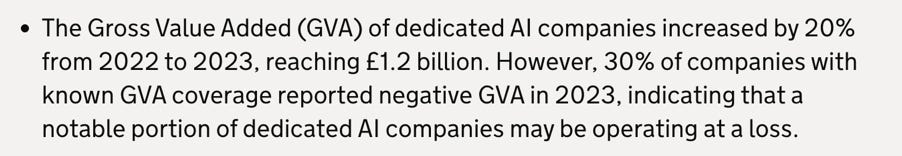

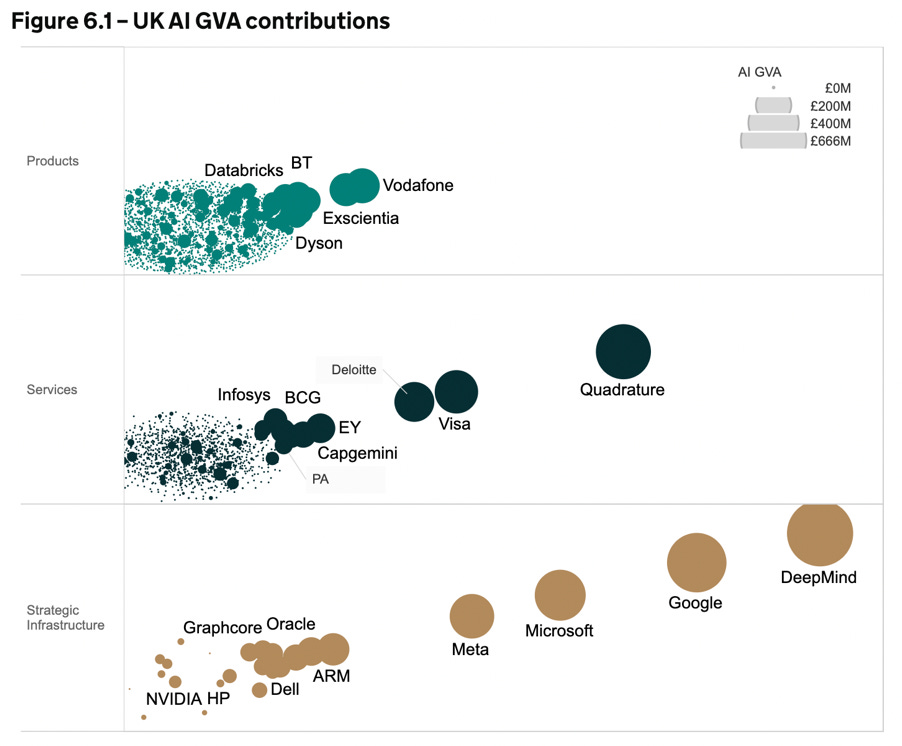

The most recent (2023) report on the UK AI sector found there were 60,000 UK jobs in AI, generating £14 billion in revenues, of which £1.2billion was ‘gross value added’ (GVA = overall value to the UK economy). To put this in perspective, in 2023 there were 60 times more people working in education, and the creative industries generated over 100 times the GVA. Looking closer, less than a third of those revenues came from ‘dedicated AI companies’. How AI is defined in both company designations and in job roles within ‘diversified’ companies depends on information from commercial databases, that often draw from company web sites. So the ‘AI industry’ is essentially marking its own homework on even the most basic issue of what it actually is.

I fully anticipate news that the AI industry has grown ‘exponentially’ since this report was produced, as hundreds of companies re-designate what they do in order to cash in on the hype and investment opportunities.

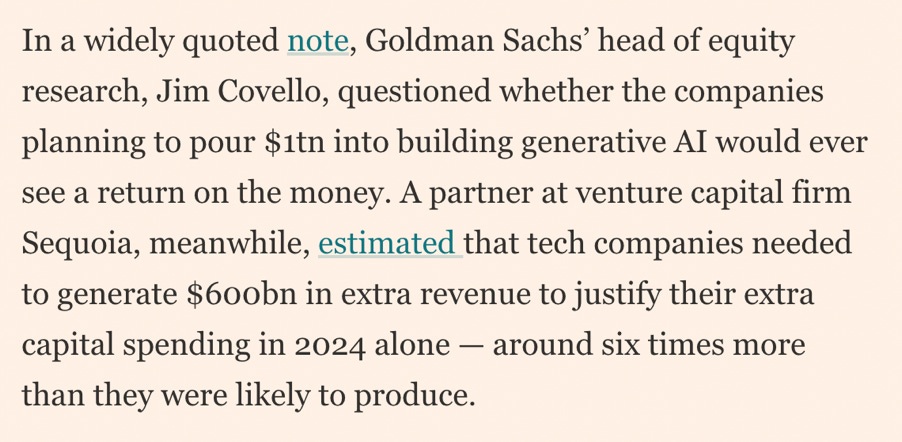

Talking of investment, ‘negative GVA’ means that companies are taking more out of the economy – especially as inward investment – than they are producing as goods and services. We know that since 2023 there has been a massive investment boom in companies that can claim to be developing services in some part of the AI stack. We know that most of this investment is not actually producing revenues from goods and services, but is being churned around the speculative economy, where mergers and acquisitions (big companies buying up small companies) can provide financial returns to investors. What this gloomy FT assessment in June really means…

… is that the proportion of UK AI companies that are in ‘negative GVA’ is likely to be much higher now than in 2023. Indeed, from these figures it seems plausible that the whole UK AI industry is currently a value sink rather than a value producer for the UK economy.

Now, much of the revenue and GVA in 2023 came from a few big, international AI corporations. The ten big AI players, accounting for nearly two-thirds of the GVA, provided only 10% of AI employment. Because basically they are big international corporations with small UK offices. Google (plus Google Deepmind), Microsoft and Meta feature large among them. Databricks is a Silicon Valley mega-corporation that is trying to secure a monopoly of AI data services by buying up everything that moves.

The offices of large international tech companies are typically managed to reduce that corporation’s tax burden and to benefit from different regulatory regimes. So although AI companies generated over £14 billion in revenues in the UK 2023, 80% of that was generated by these large firms, and in the same year (2023) the UK government missed out on £2bn in lost tax as these same firms shifted their profits overseas. In other words, economic value and tax revenues that do arise from AI in the UK may not stay here.

There are – or were - at least some UK companies among the big players. Not long after this graph was generated, Oxford biotech company Exscientia was acquired by US corporate Recursion (HQ Salt Lake City) who immediately sacked its chief executive and a quarter of its (small) workforce. Chip manufacturers ARM and GraphCore used to be British companies until both were acquired by SoftBank, banker to the Silicon Valley billionaires and founder/funder of the whole ‘national AI’ adventure. DeepMind, as I mentioned, was taken over by Google and has recently been merged entirely into GoogleBrain causing disquiet among its UK staff. Dyson is the UK company that famously moved its HQ to Singapore and axed 1000 UK jobs. That just leaves the mysterious Quadrature, that seems to be some kind of financial trading operation turning over nearly £600million with just 143 employees. Amodei’s dream is getting closer.

In fact, US takeovers of British AI start-ups have reached fever pitch since the launch of the AI Action plan, though on the day after this embarrassing headline appeared, the Government managed to announce a ‘raft of investments into the UK by leading tech companies’ to counteract the impression that the UK is just their offshore R&D lab. Examining the list, it is almost entirely made up of international consultancy firms, investors and fintech companies shifting their office locations, sometimes even within the UK (e.g. Capgemini and Netcompany), and almost certainly for tax and regulatory reasons. Only 180 new jobs are actually promised here.

This whole sorry picture can be summed up in the story of ScaleAI. With much fanfare from the last Government, Scale AI opened its European HQ in London a year ago, creating less than 50 jobs of which an undisclosed number were US employees relocating. ScaleAI is a datawork company, notorious for its exploitative labour practices and for providing the data work for ThunderForge, the US military’s ‘AI-powered, data-driven warfare’ engine. The UK was graced with its presence because London gave access to the European market for data labelling without the downsides of what seemed likely to be a tough EU regulatory environment. CEO Alexandr Wang was endearingly keen to ‘support’ the UK Government to avoid the EU’s approach:

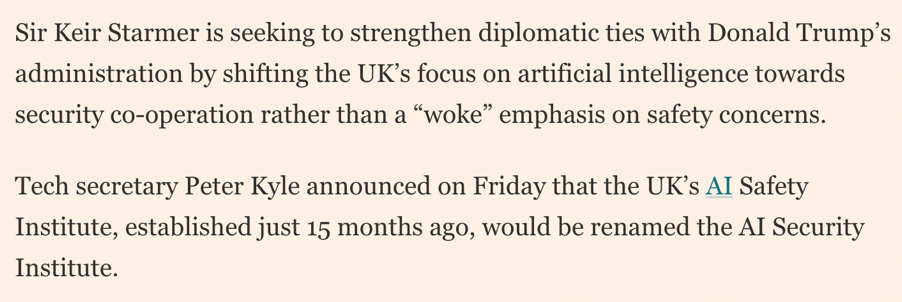

Plus la change, plus la meme chose, Wang visited Starmer on 12 February this year to discuss regulation with the new Government. By coincidence, on 13 February Starmer announced that the UK would be ‘going its own way’ on AI regulation (that is, not aligning with the EU’s pending AI Act), and on 14th he announced a further shift of policy:

ScaleAI was in fact involved in safety security testing for the US AISI until it was abolished as ‘too woke’, leaving the UK AISI high and dry. But all of this quickly ceased to be Wang’s problem as his company was acquired by Meta in June and Wang moved to head up Meta’s ‘Superintelligence’ lab. ScaleAI immediately shed 200 of its already meagre workforce because ‘we ramped up our GenAi capacity too quickly’, leaving the company worth $14bn (that’s how value gets added, you see) but with just 700 employees worldwide. Amodei’s dream gets closer still.

I apologise for spending so long on a sector of the UK economy so small that a couple of acquisitions or office relocations can produce effects of ‘expansion’. But it matters if these effects are being used to suggest that the whole UK economy would be booming if only more of it was ‘AI’. Since the government seems to have commissioned no reports on the likely impact of AI on the 99.9% of jobs in the rest of the economy, we are going to have to extrapolate from a few indicators.

One, reported in the FT in January, is that as economic prospects worsen, employers are investing in AI rather than hiring staff. Even senior executives who have gone all-in on AI report only ‘modest’ returns (all these headlines are from the past three months) but reducing staff costs can make those modest gains look better.

A recent survey (modest sample and reliability) suggested UK businesses were spending on average £321k per year on AI last year, and if it’s anything like that figure, CEOs have to find ‘returns’ from somewhere. Whatever they are currently spending is being subsidised by the AI industry itself as they try to restructure workplaces to create an enduring market, a situation that won’t last forever as some day even AI must make an honest profit. Subverting a well-known bon mot, this is the cheapest AI you will ever use.

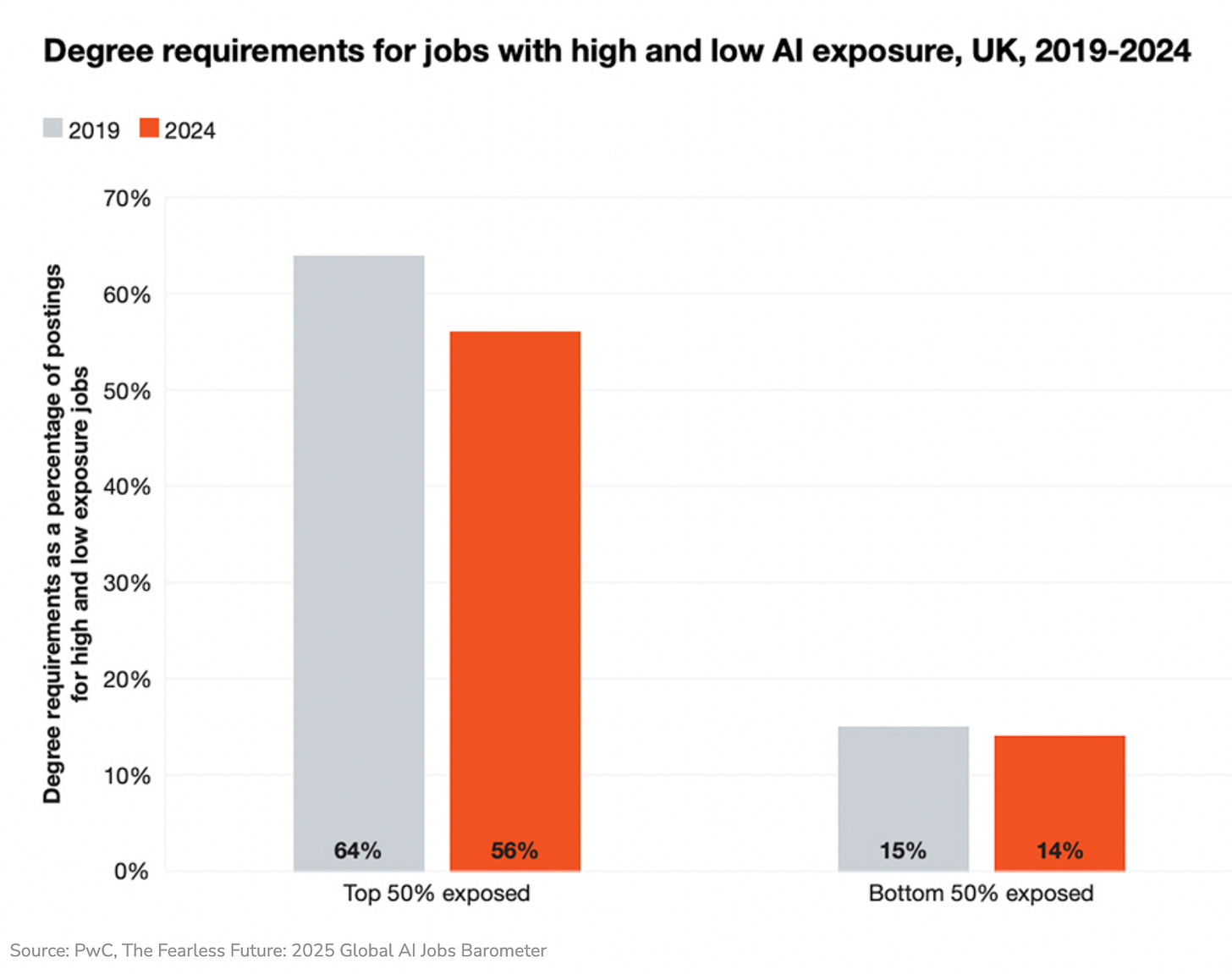

So AI does not have to enhance anything for investments in AI to create downward pressure on skilled employment. We can see signs of this happening already in the graduate job market.

For an idea of how this might play out, I have had to turn to research in other countries. The Social Policy Group in Australia has produced a comprehensive and credible report with both micro and macro economic modelling. Two caveats. The first caveat is that the Australian economy is different though comparable to ours in the UK. The other caveat is that I do not buy the high productivity and efficiency gains that SPG take as their baseline assumption. But, as I have argued, these gains don’t have to materialise for jobs to be deskilled and displaced. And anyway, the UK Government believes in them, so it should be modelling how its own assumptions play out.

The main effect SPG predict on a complex economy with a large service sector (like ours in the UK) is that AI ‘reduces labour costs without creating equivalent demand for increased productivity… leading primarily to layoffs rather than economic growth’ and ‘a cascade of job displacement and casualisation’ (page 9). With a larger tech sector, the UK has more reason to invest in AI-driven productivity than Australia. But the UK is carrying other disadvantages such as a huge over-reliance on financial services and a worse balance of trade. The 32% job displacement by 2030 that occurs in the SPG’s ‘high impact’ scenario may seem far-fetched, but since the UK Government believes some far-fetched productivity gains from AI, it’s surely worth an Industrial Strategy at least considers the risk that, with a very large professional services sector and a much smaller tech sector, the transfer of investment from skilled people to (mainly) US technologies might produce a lot of middle class unemployment.

In a retail and service economy like the UK, dependent on consumer spending and consumer credit, middle class unemployment produces a spiral of negative effects.

The one bright spot in the SPG report is that with 20% of Australians working in the public sector, the Government can stabilise the situation by ‘re-skill[ing] workers to fill critical vacancies in aged care, childcare and disability services’ (page 3) and by investing in quality jobs in health and education. The public sector plays a similar role in the UK, and with a push to become self-sufficient in sustainable food production and green energy, there is a real opportunity to boost the foundational economy too. Not to mention the creative sectors and universities, where the UK delivers real international value. With the impacts of AI disruption likely to be felt most in ‘unregulated, high-capital sectors’, the regulated, high-labour sectors that actually contribute to quality of life could be expanded. Some UK Trade Unions are coming up with proposals for safeguarding jobs in these sectors from the disruptions of AI.

But in the very sectors that could stabilise the UK economy, the Government seems determined to make every worker an AI worker, every job an AI job.

Skills on a shoestring

To secure all those AI jobs, the Government has announced £187m to be spent on upskilling young people.

‘The flagship strand of this programme “TechYouth” – backed by £24 million of government funding - will give 1 million students over three years across every secondary school in the UK the chance to learn about technology and gain access to new skills training and career opportunities.

That is £8 per secondary student per year, or £36 per secondary teacher (FTE), to ‘embed AI throughout our entire education system’. But giving money to schools is not the plan. Rather, TechYouth/TechFirst will be a scaled-up version of CyberFirst, a modestly successful programme to encourage young people into cybersecurity, run by the UK spy agency (GCHQ). Within this same pot of funding there will also, apparently, be scope for an online platform like CyberExplorers, currently provided by QA, an AI and cyber-security company that specialises in Microsoft Co-Pilot training.

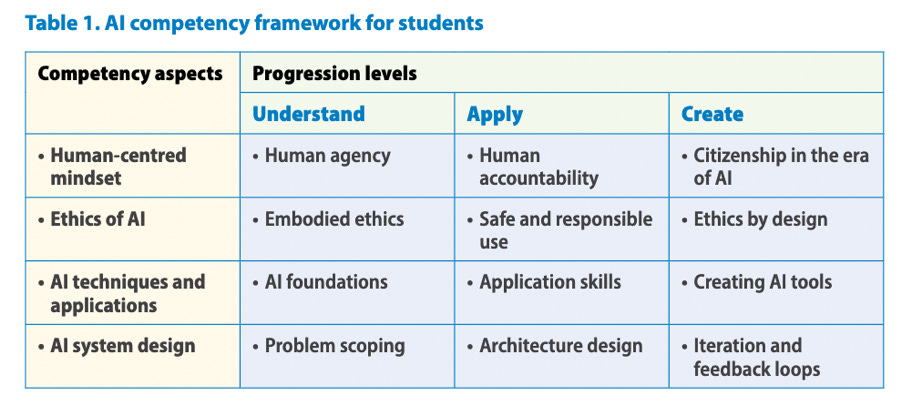

Now, it isn’t immediately obvious that spooks, security wonks and CoPilot trainers can provide the critical approaches to AI that the UN considers necessary for young people. Are the folks at GCHQ well known for their ‘embodied ethics’ and ‘human accountability’, for their ‘safe and responsible use’ of cutting edge technologies? I must look it up. An open letter from an embarrassment of experts (yes, that is the collective noun when their expertise is not being listened to) recently begged the Government to invest in ‘an informed and engaged citizenry’, working with ‘civil society and academic partners’ in their approach to AI skills. But at £8 a head, the model is surely more likely to be QA’s franchise with MicroSoft, or indeed the Government’s own partnerships with Google and AWS, that offer corporate training materials in return for lock-ins to a particular brand of ‘AI’ use.

All of that still only gets us to £24million. How will the rest of the £187million public funding be spent? The vast majority (£145m) is going to student scholarships in AI and related fields at a small number of ‘leading’ UK universities. Whether this comes on top of HE funding already committed or whether it comes directly or indirectly from other allocations, the beneficiaries are not rushing to ask. But it certainly comes on top of vast investments by AI companies themselves in PhDs, student scholarships, Chairs, partnerships, prizes and other inducements, most of them to the same elite slice of UK HE. For a decade now, commentators have demanded more public funding for AI research so that ‘the future of this powerful technology is not dominated by private interests’, and the AI brain drain can be slowed. Funding on this kind of scale could make a real difference. Except, once again, private interests seem be driving the bus. PolyAI, Quantexa, CausaLens, Flok, Beamery, Darktrace and (of course) Faculty have all ‘signed up’ to the studentship scheme, and it’s not clear whether they are signing to put money in or just to take brains out.

None of this seems likely to help teachers to adapt as AI-for-everything rips down the year groups towards pre-school. Nor does it seem likely to support education leaders as they navigate AI policy and procurement, with established tech platforms, a shoal of new AI consultants and now the Department for Education all shoving them towards unfettered adoption.

As it turns out, the distribution of funding for AI skills maps very neatly onto the division of labour in the AI stack, with a jot of valued talent at the top and millions of AI-ready data workers at the bottom, and everyone in between scrabbling to do more with less. And in that sense, perhaps AI skills for the start-up nation will do exactly what it says on the tin.

Homework marking - again

At least the Government has one homegrown AI company that it is keen to support. I have already drawn attention to two shockingly bad reports from FacultyAI regarding their attempts to generate feedback for a few synthesised examples of student work. In marking Faculty’s own homework, I assumed it was so bad because the reports were simply a footnote to their shoo-in bid to manage the country’s educational data. But that has not stopped the Department for Education’s Policy on Generative AI for schools being pegged on them.

Peter Kyle - who let’s recall had a Faculty employee working on AI policy, in his office, for the whole of last year - is continuing to claim that Faculty has a homework-marking AI tool when in truth it does not have even a minimum viable model. Faculty has marked nobody’s homework: it hasn’t even tried to. Rather, Faculty is allowing other developers to access to the educational data it is now stewarding so that they can take on the costs and risks of maybe one day producing the markerbot that teachers need so badly. Because as AI-adjacent UK thinktanks keep reminding us (I give you this report from Google/Public First as well as the ones we know and love from Faculty) teachers do too much marking when they could be teaching. Silly teachers.

Now, I’d say it’s up to teachers to know what kind of feedback is meaningful for their students’ learning and what kind is just ‘routine admin’, but we can still wonder why so much teaching work in the UK can be categorised in this way, creating the perfect opportunity for ‘AI’ to appear as a solution. It was Michael Gove, alongside special advisor Dominic Cummings, who drove the education reforms in 2010-2014 that resulted in all the standardised tests, the subject-by-subject documentation, lesson-by-lesson planning and weekly report writing that has found its way into Faculty AI’s data pool. For ordinary teachers these reforms meant a doubling of marking load in three years: a treadmill of test and mock-text marking alongside regular assessments of student ‘progress’ to support school comparison tables (an initiative that was also used to drive competition and privatisation). At the time nine out of ten teachers felt they had less time to teach and support students, and many left the profession rather than becoming marker-bots themselves.

The same pair were behind the National Pupil Database being opened up to commercial users in 2012 to ‘maximise the value of this rich dataset’, with consequences that were reported in a study titled ‘What happens when public data is shared with the wrong people’? (The authors of this report, DigitalDefendMe, have recently asked whether the inclusion of ‘pupil data’ in the latest Faculty contract means that Faculty will be have access to this sensitive dataset). Could it really be the same Michael Gove, in a different role entirely, who launched the new, low-scrutiny, ‘preferred supplier’ system for government AI contracts that proved so controversial during the Covid years? The system under which Faculty AI was the only contender for the contract to run safety testing for the UK AI Safety Security Agency? I do believe it was.

We may never know how this illustrious public career, so deeply entangled with education and educational data, has inspired Cummings’ many musings on AI. But here are some things we do know. We know that Public First (remember them from the data centre report?) was set up by two Gove and Cummings associates, who worked with them on the Vote Leave campaign, and were then inspired to set up an astroturf outfit for taking schools out of public governance. We know that Faculty CEO Mark Warner was deeply involved in both the Vote Leave campaign and Cummings’ handling of the Covid19 response when he was (briefly) inside Number 10. We know that it was Cummings who set up the Advanced Research and Invention Agency, and led it as a British version of DARPA (great writing here from David Kernohan) before handing over to Matt Clifford, the author of the AI Action Plan.

We know that, despite their supposed political differences, Gove has always been a huge fan of Tony Blair, whose Tony Blair Institute (funded by Oracle’s Larry Ellison, Amazon Web Services and SpaceX) joins Public First and Faculty in an unholy trinity of thinktanks providing ‘research’ and policy advice on AI in the public sector. Future blog posts will, I feel sure, have more to say about Tony Blair’s role in the UK’s trajectory from centrist technocracy to swivel-eyed techno-authoritarianism under the thumb of the US military state.

For now, let’s get back to Faculty and its data store, currently being touted by Peter Kyle ‘as an early prototype for ministers as they draw up broader plans to sell anonymised public data to researchers and businesses’.

I am imagining. ‘Access for free’, remember, is for developers to build prototypes and use cases that will allow the data to be commercially leveraged. And whether there is any educational value to these use cases or not, it is no longer Faculty’s business, since the mere prospect of a magic marker has put the data into their hands.

Who should be safe?

Faculty’s business is data, not education. Their main commercial product, Frontier, is a data analytics layer that promises ‘better, faster decisions’ from organisational data, and the company’s success in securing government contracts is based on a similar model: sweeping up tracts of public data to offer it back as an intermediary layer between privatised apps and services.

As you might imagine from a company that is focused on ‘the frontlines of the world’ and colours itself khaki, much of Faculty’s expertise in data has been honed in the military and security sectors. It has partnerships with major defence companies to develop AI for autonomous weapons, and its role in security and border control was one reason for handing Faculty the safety testing contract for the UK AI Safety Security Agency. See, it is very easy to confuse safety with security, and ‘keeping data secure’ with ‘using data in security systems’. So here is a short primer:

‘Security systems’ use personal data such as facial recognition, location data, known contacts and home addresses to make people as unsafe and insecure as possible - to detain them, deny them border crossings, and target them for violent death.

Keeping data secure means not allowing data about people to fall into the hands of anyone who might use it to make those people unsafe, something the UK military has struggled with in the very recent past.

Now, it almost seems as if the first meaning of security is the opposite of the second, but there is an important difference. The people in the first scenario are bad people and the people in the second are good people, which is why ‘security’ can mean such opposite things. So deciding which kinds of people are which, who to keep safe and who to deprive of safety, and in the interests of what national ‘security’ agendas, are among the gravest responsibilities of the state.

These are the kind of decisions that should not, you’d think, be farmed out to algorithmic systems or the unaccountable private enterprises that own them. Yet even now, three years into the story that ‘generative AI’ is the future of economic growth, most UK government spending still goes on predictive AI systems: that is, systems for making decisions about people’s lives. Systems like the ‘real time data-sharing network’ Palantir is building across UK police forces, or Palantir’s software, offered to the Ministry of Justice, for calculating prisoners’ reoffending risks, or the massive investment in precision targeting and autonomous weapons unlocked by the Strategic Defence Review - substantially penned by Palantir. And while it might seem odd that a foreign company has so much power in UK Government, dw, Palantir is a long-time partner of Faculty. Why, as long ago as 2010 our own GCHQ was employing Palantir’s software to gather data from around the world, reassured by the fact that the company had every appearance of being set up by the CIA.

How reassuring, also, that there are such close ongoing ties between the UK state and the AI industry so they can always be on the same page about these critical issues. The former Director General of GCHQ and the very newly retired Chief of Air Staff of the UK Armed Forces have both joined Faculty AI in recent months - the links are to ‘advisory notices’ from the Committee on Business Appointments. Faculty is cited or mentioned 41 times in the Defence Committee’s report Developing AI Capacity and Expertise in Defence, the one that led to the massive spending boost for AI warfare.

All this might seem low rent compared with the US, where the world’s biggest AI companies are signing multiple contracts with the world’s biggest war machine, AI chief executives are being sworn in as US army officers and Palantir is in line for a contract to track the data of every US citizen. But that same Palantir, whose CEO boasts of ‘powering the West to its obvious innate superiority’, has been promoting the idea of a common operating system across UK government. Word has it that civil servants facing DOGE-style cuts of 15% are being forced to report their ‘time saved with AI’, though it’s not clear if they also have to log the time wasted, the tasks that take longer, or all the times AI makes them miserable, or whether using more AI will make their jobs safer or less secure.

So here’s an idea. Perhaps civil servants could instead be developing the expertise to offer ministers independent guidance on public sector AI. Independent from the US military and security companies that are cited in every report and shooed in for every public contract. Independent of the seconded tech workers proposed for every government department, and independent of the ‘independent think tanks’ that are stuffed with Silicon Valley assets.

In early 2023 I wrote about the dangers to the public sector when corporate data and data services become core to service delivery (‘AI and the privatisation of everything’). While this danger has only intensified, I now see an even more potent threat. The neoliberal state is being transformed into an authoritarian, securitised state, with AI acting both as a powerful narrative for the manufacture of consent, and as a means of co-ordinating commercial and state capacities to govern through the use of personal and social data. The government’s role in collectivising risk to provide shared social security has been replaced by an obsession with ‘national security’ and military spending, as illustrated by the Orwellian rebranding of AI Safety as AI Security. From monitoring AI risks to using AI for surveillance and war.

And here’s a last thought for my friends in education technology. When edtech is bracketed with ‘defence, justice and security’ as opportunities for a cabal of cranks and spooks to do what they like with UK citizens’s data, perhaps it’s time to get off the AI train.

Really? Yuck. Chatbots are bad enough.

Thanks, Helen, for an encyclopaedic survey of where we are at. 'Barricades' hardly suffices.