O, there be players that I have seen play, and heard others praise, and that highly, not to speak it profanely, that, neither having the accent of Christians nor the gait of Christian, pagan, nor man, have so strutted and bellowed that I have thought some of nature’s journeymen had made men and not made them well, they imitated humanity so abominably.

Will Shakespeare, Hamlet III(ii)

The original definition of ‘AI’, coined by John McCarthy in Stanford in 1955, was ‘the science and engineering of making intelligent machines’. To McCarthy and his Stanford colleagues, the meaning of ‘intelligent’ was too obvious to spell out any further. Marvin Minsky, writing in 1970, reiterated that: ‘Artificial intelligence is the science of making machines do things that would require intelligence if done by men’. Many definitions of ‘artificial intelligence’ in use today rely on the same assumption that computational ‘intelligence’ simply reflects what ‘intelligent people’ can do. Definitions such as here, here, here, and from today’s Stanford Centre for Human-Centred AI here all follow the same pattern. Intelligent people don’t even have to be men these days, but ‘we’ know who ‘they’ are.

In the guise of starting from something self-evident, the project of ‘artificial intelligence’ in fact serves to define what ‘intelligence’ is and how to value it, and therefore how diverse people should be valued too. Educators have good reason to be wary of the concept of ‘intelligence’ at all, but particularly as a single scale of potential that people have in measurable degrees. It is a statistical artefact that has long been scientifically discredited. It has been used to enforce racial and gender discrimination in education and to justify diverse forms of discriminatory violence, particularly over colonial subjects.

Biologist Stephen Jay Gould described the project as:

‘the abstraction of intelligence as a single entity, its location within the brain, its quantification as one number for each individual, and the use of these numbers to rank people in a single series of worthiness, invariably to find that oppressed and disadvantaged groups—races, classes, or sexes—are innately inferior.’ (Gould 1981: 25. Cited in Stephen Cave (2020) The Problem with Intelligence: Its Value-Laden History and the Future of AI.

The term ‘human’ is problematic for similar reasons. Unless its use is carefully qualified (and even then) ‘human’ all too often takes a particular fraction of humanity - white, anglo-european, male, educated, for example – as its reference point and norm. Most academics have enough sense of the history of these two terms - ‘human’ and ‘intelligence’ - to avoid using them in an unexamined way. Particularly when it comes to student learning, when we recognise there are a diversity of ambitions, identities, experiences, capabilities and cultures in the classroom, all of which can be resources for learning. And yet, since ‘artificial intelligence’ colonised the educational discourse, ‘human intelligence’ has begun to be used as though it is not only a real and self-evident thing, but self-evidently what education is about.

The value of this term to the AI industry is obvious. ‘Human intelligence’ is a palliative to anxieties about the restructuring and precaritsiation of work: don’t worry, there are still some things our models can’t do (yet). And yet the space of work that has not been declared computable today, or tomorrow, or the day after tomorrow is narrow and narrowing, and only the AI industry is qualified to define it. ‘Human’ in relation to ‘artificial’ intelligence turns people into props for data systems (humans in the loop). Props that make system outputs more accurate, safe, ethical, robust and useable, only to be removed once their input has been modelled and datafied. (Or, perhaps, when making AI safe and useable proves too expensive after all.)

This is what the WEF means by ‘working productively alongside AI’.

But it is not clear to me why anyone who cares about education would catch the term ‘human intelligence’ from the cynics who are throwing it our way. Not surprisingly, given the history of both terms, if you pay any attention you can hear how regressive and divisive it is. A small number of ‘human intelligences’ will be free to maximise their potential for innovation and originality, their entrepreneurial decision-making and wise leadership. So rest easy that there will be highly paid jobs for AI engineers and company executives.

However, these people can only max out their human qualities if they are set free from other kinds of work - the boring, repetitive and uncreative. We are supposed to believe that this work is being ‘automated’ for everyone’s benefit, but this is manifestly not so. Research assistants aren’t promoted to other, more interesting roles when ‘AI research assistants’ come online. Rather, the work they do is likely to become more pressured and less valued, or to disappear. There are still drivers (‘human overseers’) behind self-driving cars, annotators (‘data workers’) behind large language models, human personnel swiping left to authorise AI ‘targets’ for bombing, and teachers uploading lesson plans and topic maps for ‘teacherbots’. And it turns out there were 1000 Indian data workers behind Amazon’s ‘fully automated’ stores in the UK. The work does not vanish, it is just routinised, cheapened, denigrated, frequently offshored, and always disappeared from view.

The other ‘human’ who appears in the AI mirror is not running companies or registering patents but doing ‘emotional’ work: that is, work that has always been badly paid or removed from the sphere of paid work altogether. The work of care, service, community building, non-monetisable forms of creativity (craft, leisure, play), mending things and people who are broken. These forms of ‘human intelligence’ are not ‘increasingly prized’ at all. Instead, university managers are calculating how many student support staff can be replaced by chatbots. Academics who invest time and care in students (‘the human touch’) are threatened with redundancy. Schools are relying on volunteer counsellors to cope with the tsunami of mental distress (my local school has 13) while employing highly paid data analysts. In fact, the people who do the most to actually humanise the experience of mass education for students seem to be the most replaceable. Enjoy the feels, because ‘emotional intelligence’ doesn’t ask for job security.

It’s funny how this happens, but it seems work that is highly rewarded because ‘uniquely human’ is most likely to be done by white, western, well educated men, preferably in STEM disciplines. While work that is undervalued because it is ‘only human’ is most likely to be shouldered by the rest of the world. And this work is constantly being reorganised as data work. Every gesture that can be captured as data is modelled, and whatever is left is rendered as a behaviour, to be governed by the model and its data-driven routines. Between highly paid ‘innovation’ and the non-computable work of the foundation economy - work that literally requires the human touch - AI is the project of datafying everything else.

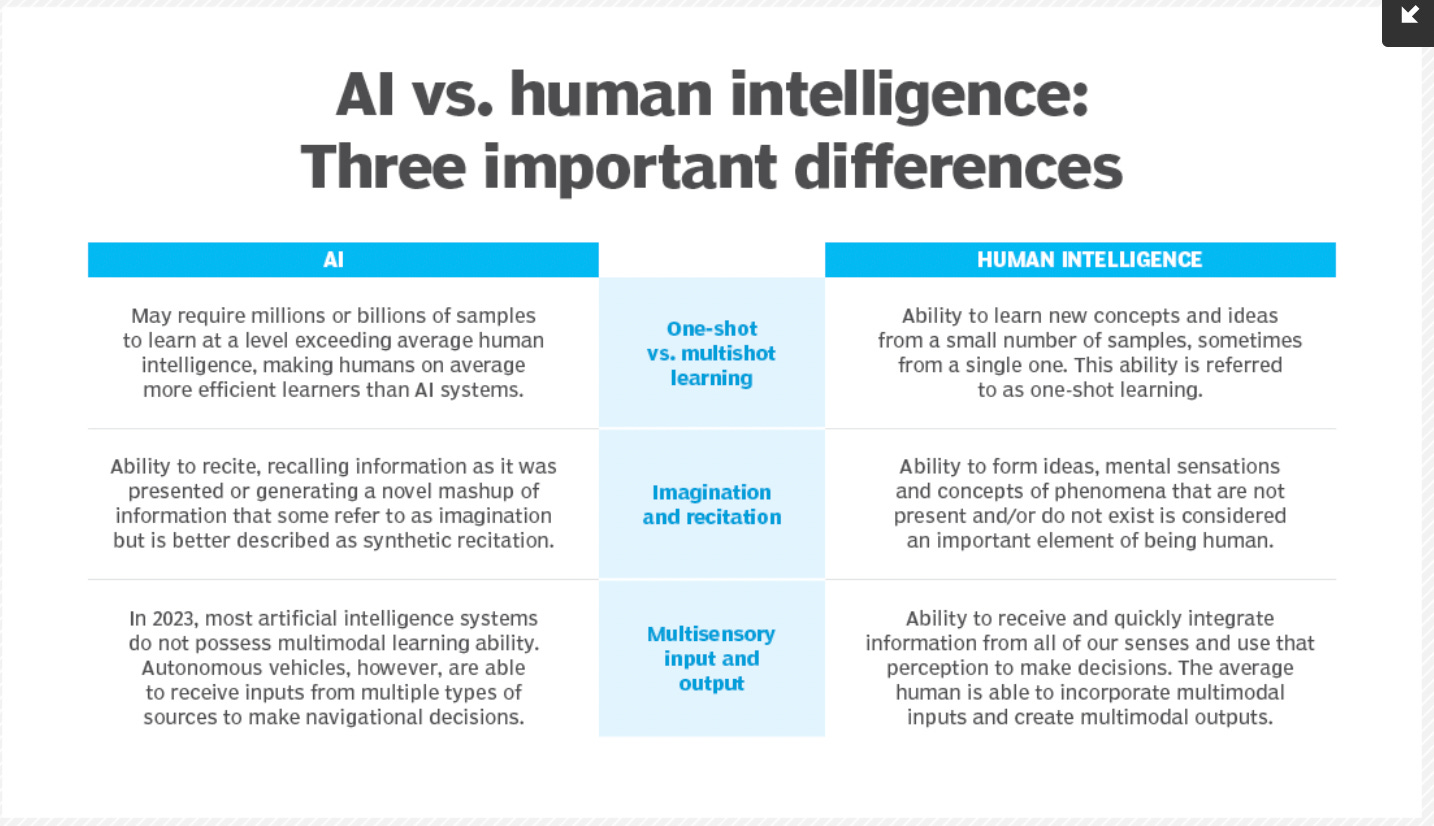

A recent post on TechTarget defined the ‘important differences’ between artificial and human ‘intelligence’ in ways that make clear everything in the right hand column is already available on the left. ‘Human intelligence’ is apparently being flattered but actually being erased. These definitions are so shallow, cynical and vacuous, I can only read them as deliberate provocations to the education system that is supposed to fall on them gratefully. ‘Mental sensations and concepts of phenomena that are not present’? I can’t see that passing even ChatGPT’s floor-level bullshit detector.

What these self-serving comparisons produce is a double bind for students and intellectual workers. Submit yourself to the pace, the productivity, the datafied routines of algorithmic systems, and at the same time ‘be more human’. Be more human, so that you can add value to the algorithms. Be more human , so more of your behaviour can be modelled and used to undercut your value. Be more human so that when AI fails to meet human needs, the work required to ‘fix’ it is clearly specified and can cheaply be fulfilled.

We can see these demands being interpreted by students as both a need to produce optimised texts – according to a standardised rubric or, perhaps, to satisfy an automated grading system – and to write in ways that are demonstrably ‘human’ (whatever this means). No wonder they are anxious and confused.

I spoke about this double bind for students in a recent podcast for the UCL Writing Centre: Student writing as ‘passing’. (recording soon available from this link). I also explore some of these issues in a post on the ‘unreliable Turing test’. The problems and disruptions posed by ‘AI’ are not only for education to suffer, but the question of what it means to pass as both authentically human and valuable to the data economy is particularly pressing in the education system. It surfaces in all the concerns about assessment and academic integrity. But only to address it there is to fail to recognise the challenge that is being thrown down to universities by big tech, epistemologically and pedagogically, as well as through the more mundane challenges of draining talent, buying political influence, and competing for educational business.

I hope you enjoy these new offerings. All their human imperfections are my own.

This is spot on. Is part of the problem that we, or at least governments, corporations, and institutions, understand humanity only in contrast or relationship with machines? BTW, I do love the bits you write. Everything you have posted in this blog to date has either articulated things about AI that I have pondered better than I can or sent me down new paths. Please keep it up.

I like the framing of the "double bind", and the way you've articulated the illusion act being perpetuated by AI hype contingent. It does feel really dissonant to hear the pressures to be both more human and more model-friendly at the same time. It hurts to see how readily AI is prized (mostly by its sponsors, of course) above human connection or participation, and how some of the AI systems incentivize the perpetuation of that value scheme.