Our actions and creations do have power over us. This is simply true … The danger comes when fetishism gives way to theology, the absolute assurance that the gods are real. Graeber, 2005: 431; cited in Thomas et al. 2018

This essay/post is about AI fantasies and why they matter in education.

When European anthropologists first met the power objects of people from different cultures, they called those objects fetishes. I wouldn’t use the word if it only had that original, colonial meaning. But social theorists, from Karl Marx onwards, have turned the term against colonising societies, with their supposedly more rational beliefs. Because things, ways of producing and using things, really do shape our lives. Marxists are interested in how workers are compelled by the factory system, or by post-industrial technologies in networked systems. Other social theorists are interested in how consumers relate to consumer products, or users to their digital devices.

As David Graeber says, we really are entangled in powerful relationships with things, but we can be fooled if we locate power in the things themselves, separate from social relations and meanings. If we allow things to become gods or monsters, masters or servants, with agency of their own.

Agency everywhere

However we understand the hype around them, it seems we can hardly help ourselves relating to synthetic models as though they have agency. Anna Mills recently started a great thread on alternatives to ‘hallucination’:

You can find the ideas she collected summarised here. But while we can discuss it sensibly, the feeling of ‘conscious experience or intent’ is hard to shake off.

Of course, terms like ‘learning’, ‘collaboration’ and ‘hallucination’ are being fed into the popular discourse deliberately. In the sense that ‘artificial intelligence’ is a project to designate certain computational systems as ‘intelligent’, these terms are not just packaging but essential moving parts. The first person (‘I’, ‘me’) address of natural language interfaces - that many people are now using to access other apps and services - is also a deliberate piece of design.

To use a term from social theory, when a chatbot uses the first person ‘I’, users are being ‘interpellated’, that is ‘called into place’ or ‘called to respond’ as if to another person. I got that from Althusser, who was writing about ideology, but here’s Airenti (2015) from a mainstream cognitive science perspective:

humans are attuned to turn-taking and interactive exchanges with each other, and they apply this approach to artificial entities as well, treating them as interlocutors while being fully aware that they are not human. However, once an artificial entity is in the position of an interlocutor, humans may in fact start attributing goal-directed behavior, mental states, and beliefs to it.

Social or cognitive science: both suggest that, when we are addressed as a ‘you’ by an ‘I’, we respond as an ‘I’ to a ‘you’. As it turns out, some users respond in rude, mean and oppressive ways to chatbots, and I don’t think this is a trivial point (more on this later). But still, we take our turn, and in turn taking we assign the other party some qualities of being a person: an ‘I’ like me, a ‘you’ like other people.

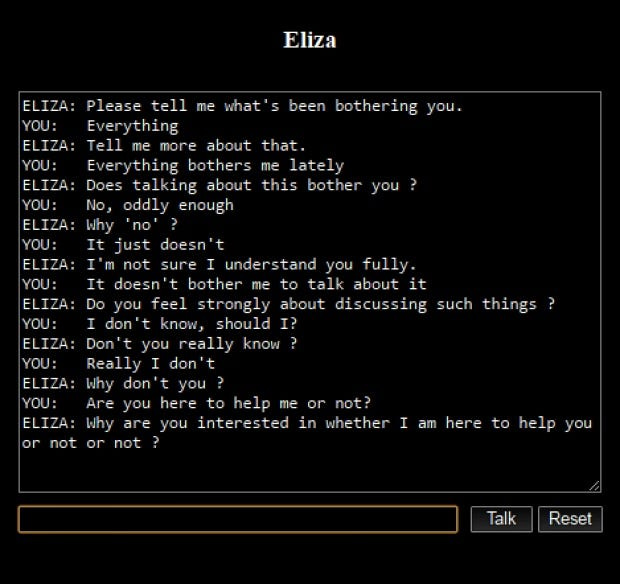

The first chatbot, Eliza, was a basic pattern-matching program that its developer Joseph Weizenbaum, was ‘shocked and surprised’ to find being treated as a partner in conversation, even by the co-workers who had helped design it.

Inside knowledge is no defence: people may or may not remember that the whole generative AI hypefest kicked off when Google engineer Blake Lemoine claimed that the LAMDA version he was helping to train had become ‘sentient’.

The speed and flexibility of transformer models have certainly revolutionised chatbots, making conversation more sustained and fluent, able to range over a far larger ‘context window’, and to deal with a far wider range of prompts. But the big tech companies have not stopped at fluency. Last September, Meta launched 28 ‘conversational agents’ with the faces, back-stories, and alleged ‘personalities’ of celebrities and other characters. The huge cost of human writers scripting these characters, not to mention the licensing of celebrity personas, show the company’s priorities. Rather than improving the underlying models, they are throwing their dollars at the user interface, even though this makes the model more resource hungry and inefficient to run. A September 2023 report from Public Citizen on the dangers of ‘human-like AI’ found that it is cheaper to design without anthropomorphic features, but:

Anthropomorphic design can increase the likelihood that users will start using a technology, overestimate the technology’s abilities, continue to use the technology, and be persuaded by the technology to make purchases or otherwise comply with the technology’s requests.

Yea, big tech gonna tech. Still, these features are appealing to a strong underlying belief in other minds, and I feel this says something about human thinking that challenges the idea of ‘intelligence’ put forward by the project of‘AI’.

‘Self’ing others, othering ourselves

This is a section about psychology – skip ahead if that’s not your thing.

Claims about human beings in general have a terrible history of being used by particular (white, Anglo-European. male) people to justify horrors against particular others. I’m aware of colonial history when I use the words ‘human thinking’ and ‘the human mind’. And I believe that everything we share as a biological species should be understood through specific cultural expressions and meanings, as well as particular embodied realities. But I also worry when critical social scientists abandon human minds to the positivists and the statisticians.

When psychology becomes reduced to, on the one hand, ‘brain sciences’ with their MRI scans and ‘neural’ models, and on the other hand statistical measurement and management of human behaviour, I think we are missing out on essential resources for teaching and learning. Resources that might provide some resilience against the definitions and techniques of the AI industry too. AI recruits neuroscience for its spurious claims to build artificial ‘minds’, and it depends on statistical management of human behaviour to keep people hooked into particular relationships with its data systems. It uses both to make claims about ‘learning’ that have real effects on how its technologies are adopted in education, as well as pushing aside more progressive ideas about how people learn.

The resources of psychology are broader than this. From the perspective of cultural, social or developmental psychology, human beings can be seen as social animals. Animals that have evolved to live in complex groups, with shared goals and needs, and with bodies that can survive only in relation to other natural beings, and other bodies of a similar kind. Needing to solve problems collectively is where language and culture enter the human story – always particular languages and particular cultures, but with a universal need to mediate practical, material activities.

I’ve recently taken an interest in research on mirroring (yes, this is ‘brain science’, but bear with me). There is much evidence that:

other-related information mapped onto self-related brain structures can modulate the ways in which humans and other animals respond to others.

What this means, I think, is that our brains respond to seeing other people doing things in much the same way as when we are doing them ourselves. That does seem to me quite contrary to what individualist Western psychology would expect to find.

Brain science and brain imaging are blunt instruments, so I don’t want to credit them with more insight or precision than they deserve. What used to be called ‘mirror neurons’, for example, are now known to be extensive systems:

found in a variety of brain areas and animal species, encoding not only observed actions, but also emotions, spatial locations, decisions or choices, rewards, the direction of attention, and beliefs.

So the capacity to experience ourselves as others, and others as ourselves, is fundamental to social animals. Empathy is written through our mental repertoire. (Western) philosophers and Silicon Valley red-pillers may ponder how we know other people are real, but we can only experience other people as intentional, emotional, agentic beings, just as we experience ourselves. Our mental life doesn’t seem to begin with a coherent ‘I’, let alone in some logical representation of the world, but in shared agency.

All this is obviously relevant to learning. Lev Vygotsky puts it like this:

Every function in the child’s cultural development appears twice: first, on the social level, and later, on the individual level; first, between people (interpsychological) and then inside the child (intrapsychological). (Vygotsky, Thinking and Language 1978: 57)

Mental activity, in Vygotsky’s terms, is social activity. His colleague, the linguist Mikhail Bakhtin, described all language as dialogue: every utterance is ‘pregnant with responses’, even when a speaker is alone. Alongside other Russian psychologists of the early C20th (Leontyev and Volosinov for example) Vygotsky and Bakhtin are actually much closer to certain indigenous ways of thinking about minds than to Anglo-European psychology. This is something that has been noted by (among others), Mary E. Romero, Luis Moll, and recently by a number of Maori scholars. In these traditions, mind is inherently dialogic, inherently social, inherently empathic to the world. And teaching-learning are two sides of the same coin.

When they are first negotiating these relationships between other and self, public and private worlds, we find children often in dialogue with themselves. We find them lending personalities and voices to dolls and spoons, imagined friends and contemporary artefacts like mobile phones. Again, indigenous ways of thinking celebrate children’s natural empathy, their recognition of ‘other kinds’. In Braiding Sweetgrass, Robin Wall Kimmerer writes: that ‘paying attention is a form of reciprocity’. Cognitive science tends to treat this ‘othering’ as a kink, a quirk, the kind of ‘cognitive bias’ that makes human beings fallible and rather stupid. But it is essential to the development of minds.

Turing’s troublesome test

The othering or empathic quirk is also essential to the Turing test, though it is not often remarked on. The test is a thought experiment that remains at the heart of the ‘artificial intelligence’ project. In this test, a person who is designated the ‘judge’ must ask: does this behaviour, do these system outputs, suggest a mind at work? If the answer is ‘yes’, the system can be considered intelligent. But the only way of making this assessment is for the ‘judge’ to consult with the experience of having a mind, and of interacting with other minds, and to ask: ‘would my experience look like this, from the outside?’

Turing himself admitted that:

The extent to which we regard something as behaving in an intelligent manner is determined as much by our own state of mind and training as by the properties of the object under consideration. (Turing (1948) p. 431, cited in Proudfoot 2022)

Turing was undoubtedly a behaviourist in his view of other minds – the man and woman, or man and machine, that were the subjects of his test. But the test also requires a third person, someone who Turing, as a scientist himself, perhaps identified with (‘our own state of mind’). Someone not only introspective but empathic too. And having minds of this kind, we don’t need much evidence to decide that another mind is there.

We can use this quirk of empathy to play with, and to learn with, and to develop deep relationships with: but it can also be used to play with us. Things, as Graeber noted, have real power over us through the social relations we are entangled with. And as writers on fetishism have observed, from Marx to Agamben, and from Freud to Baudrillard, a belief in the power of things-in-themselves can become a compulsion, a place where power can be exercised.

Gods and monsters

Far from encouraging us to examine the illusion of agency in their designed systems, big tech encourages us to indulge in it. What kind of others are we encouraged to find in these humanised chatbots and media models? What kinds of people are called out of us, to interact with them?

One powerful imaginary is that AI models are more than human, especially ‘smarter’, where ‘smart’ is an undefined and unexamined good. ‘Intelligent machines augment intelligent humans’, writes Marc Andreessen, producing ‘technological supermen’. On the public pages of OpenAI we find a more democratic version of the same promise: intelligence as a ‘great force’ through which all of humanity will be ‘elevated’.

AI developers are the ‘legends’, according to Marc Andreessen, that bring these wonders into the world. ‘Intelligences’ in the service of ‘superintelligences’, according to Nick Bostrom. Why does AI have ‘godfathers’, after all? Why not just ‘fathers’ or ‘grandfathers’ (I mean, obviously there aren’t any mothers involved). The idea that they are fathering gods is there in plain view.

By elevating ‘intelligence’ to a kind of mystical power or absolute good, these legends are putting their own intellectual and technical ambitions beyond constraint. This is the main purpose of this meme, I think, and it is directed most powerfully at investors and would-be regulators. Since ‘intelligent’ technology might be capable of anything, since its value is infinite, to resist or regulate or just fail to prioritise it is to destroy the gods. Andreessen describes any constraint on developing ‘artificial general intelligence’ as ‘a kind of murder’.

The flip side of the god story, most famously held to by Geoffrey Hinton, is that because the intelligence is so powerful and unknowable, it can turn into a monster. Again from the public pages of OpenAI, doubters who ‘think the [existential] risks of AGI are fictitious’ are sent off to study the book of Revelation where we learn that ‘we could all be killed, enslaved or forcibly contained’. It should worry all of us, by the way, that people at the very top of the AI industry are treating this kind of outcome as a manageable operating risk.

The fantasy of creating a god or monster that may make you immortal, or enslave you, or possibly both (it’s a kind of S/M dynamic I guess) may be genuinely believed by some of the men who espouse it. It is certainly a fantasy about power. Emily Gorenski, in a brilliant post on techno-futurism as ‘making God’, connects it with the horrors of the atom bomb. No wonder, she suggests, the US military have been so keen to fund decision-making systems that could take on responsibility for the god-like power of modern weaponry. I am not sure this is the motivation, though. Autonomous weapons systems have been used to kill people since 2021 at least, and the psychological effects on the perpetrators don’t seem to be a denial of responsibility but, on the contrary, a glorification of the power that is killing from a distance, while remaining physically out of harm’s way.

Meredith Whittaker argues that all contemporary AI is built on surveillance. And surveillance is essentially a fantasy of perfect information providing absolute control. Palantir’s chief exec, Alex Karp, gleefully promotes the company’s AI Platform as ‘a weapon that will allow you to win’, both in the literal sense of killing people (‘correctly, safely, and securely’) and in the militarised business-speak of ‘seeing off the competition’. OpenAI’s Sora seems to have been trained extensively on gaming worlds, that often take the perspective of the first-person shooter (OpenAI has recently rescinded its ban on real world military applications too). And with no sinister irony at all, a palantir is one of those glass orbs that Sauron uses in the Lord of the Rings to see everything from the top of his tower.

All these projections of power from afar can be recognised in what feminist Donna Harraway called the ‘god trick’ of AI. Writing towards the end of the last century, she and other feminists- like Alison Adams and Lynette Hunter - were critiquing an earlier generation of AI systems, that relied on symbolic logic and not on big data to build their god-like representations of the world. But the critique still holds. ‘Intelligence’ is the power to act at a distance, to think and plan and sense beyond the limits of the body, to abstract from the immediate situation. Take this to extremes, and ‘intelligence’ is the disembodied eye in the sky, invulnerable to death, and so removed from human morality and accountability.

Another feminist writer of that C20th, one less remembered and celebrated than Haraway, was Joanna Russ. Nearly half a century ago she wrote about technology as a ‘cognitive addiction’.

It is because technology is a mystification for something else [capitalism] that it becomes a kind of autonomous deity which can promise both salvation and damnation. I might add that all the technophobes and technophiles I have ever met are men… Both technophilia and technophobia are owner's attitudes. In the first case you think that you have either power or the ear of the powerful, and in the second case, although you may feel you have lost power, you at least feel entitled to it.

When she calls out ‘the common science-fictional device of "solving" the quality of life by giving people immortality’ she might be taking aim at the ‘longtermist’ view of many Titans of big tech. The view that people’s suffering today matters very little in the grand scheme, which is to overcome the limits of the human body – at least of some human bodies - and soar away from its dreary suffering and its messy social entanglements:

‘We will gain power over our fates. Our mortality will be in our own hands. We will be able to live as long as we want’ (Ray Kurzweil, The singularity is near: when humans transcend biology, 2005, p.9, cited in Cave 2020, a critical report on the doctrine of transcendence)

Russ has a cure for this:

I suggest that politics and economics take the place of the kicked technology-habit until the victims' intellectual taste buds recover and they find themselves capable of thinking in more practical terms, especially about money and power. When they do this, they will find interesting historical evidence pointing to the non-autonomy of technology and its subordination to economic and political uses.

Servants and girlfriends

The god-spiel is really for the legends of tech, the investors, the CEOs, the corporate clients and the potential partners who need to be convinced that they are buying immortality. (For now, AI does seem to have wondrous powers of wealth generation). The monster doctrine is for governments and would-be regulators, who must be persuaded to rule (or not rule) in ways that favour the ‘native’ big tech companies: the only defence against ‘AI in the wrong hands’.

But at the user interface, the ‘other’ that is produced by generative AI is neither god nor monster. Leaving aside the celebrity avatars for a moment, the underlying models are prompt-coded to be polite and submissive. They apologise and correct themselves when they are challenged. They refuse to express an opinion. They are eternally available. They ask to be treated, in fact, as servants in the office or research lab, just as voice assistants ask to be treated in the home.

The term ‘robot’ - from the Czech for ‘serf labour’ – was first used to describe artificial workers by playwright Karel Čapek, and taken up by Isaac Asimov in his series of Robot stories. From the first (‘Strange Playfellow’, 1940) Asimov explored the relationship of robots and human beings in terms of servitude. His famous ‘three laws of robotics’ insist that any human-created intelligence is created subordinate.

Although I will do more justice to it in another post, I want to mention here Meredith Walker’s brilliant essay Origin stories: plantations, computers and industrial control. She sets out a history of computation as deeply entwined with processes of management and control, of ‘intelligence’ being installed in new technologies and technologized regimes in order to discipline workers, and of workers becoming dehumanised in relation to these systems. She does not, by the way, equate the very different experiences of slavery and free labour. She does explore continuities in the techniques of discipline and control.

Today’s ‘generative AI’ promises to automate the kind of work that is done at the entry level of professions. But here too, the goal of restructuring is taken forward partly by denigrating and dehumanising the work involved. Professionals are wooed by the promise that they can be more innovative, creative and productive, that they can become more human, if only they can be relieved of tasks that are low-level, mindless and inhuman.

Of course this is simply dishonest. Businesses don’t want to employ more highly skilled workers if they can employ fewer workers and make them more productive. If they can turn time-intensive and expert work into work that is routinised and can be done by cheaper staff. But more subtly, this approach is derogatory of whole categories of work and the people who will continue to do it, so long as their labour can be cheapened enough. These people are more likely to be female and non-white, and precariously employed. It is no coincidence that the type of work being allocated to chatbots in wealthy economies is the same that is being off-shored to countries with cheap labour (e.g. customer care, basic triage, IT support). In fact, as large language models incorporate the labour of thousands of precariously employed data workers, the process of reconstructing labour through synthetic ‘AI’ is entirely consistent with the process of off-shoring, which is also accompanied by datafication and technological forms of management.

There is now extensive research into the gender bias in the design of AI voice assistants. For example Borau et al. (2021) found that female chatbots were felt to be ‘more human and more likely to consider our unique needs’:

injecting women’s humanity into AI objects makes these objects seem more human and acceptable.

Female-gendered chatbots are often targeted by users with sexualised comments and worse. Readers will remember how Microsoft’s Tay, a teenage girl avatar and ‘conversation assistant’, was taken offline after 16 hours of being sexually abused and made to spout hate speech.

While the new generative text models are not given gendered identities – and big tech has taken steps to improve the gender balance of voice interfaces - this is a design space in which feminised models are the norm. (Just for the LOLs, I generated ten images of a ‘personal assistant’ using Stable Diffusion, no other cues, and they were all clearly gendered female.)

Here’s Marc Andreessen again (in ‘why AI will save the world’):

Every person will have an AI assistant/coach/mentor/trainer/advisor/therapist that is infinitely patient, infinitely compassionate, infinitely knowledgeable, and infinitely helpful. The AI assistant will be present through all of life’s opportunities and challenges, maximizing every person’s outcomes.

Elsewhere he describes an AI personal tutor providing ‘the machine version of infinite love’. This is the same guy whose VC company has just invested $5m in non-consensual, deep-fake pornography, so there are clearly different versions of infinite love on offer.

But even the ‘AI assistant’ version I find feminised in a troubling way. In the classic angel/whore dyad, the good woman is the infinitely patient helper, the ‘angel in the house’ who puts her own needs and wants entirely to the side. Her counterpart is the sexualised girlfriend, who can now be designed in DreamGF or Replika or EvaAI to meet the user’s every whim. In both cases, ‘she’ is designed to respond only to the agency of the other.

Not surprisingly, in the fake girlfriend business, abuse is very common. Karina Saifulina, EvaAI’s Head of Brand, admitted to the Guardian that ‘users of our application want to try themselves as a [sic] dominant’. Georgi Dimitrov, CEO of DreamGF, told Sifted: ‘People want to get their fetishes out and they will pay for services to do that. I believe that it’s better they do this with an AI chatbot, which doesn’t have feelings and doesn’t get hurt, rather than doing it to real girls’. The relationships we are invited to enter with chatbots, sexualised or not, can’t help involving power. That is surely what it means to be a ‘user’ in relation to another entity that is designed to seem human. Of course, that is going to mean that other cultural dynamics of domination and submission are going to be invoked.

Beyond infinite love

So, I am not going to suggest that everyone interacting with a chatbot is indulging in power play. Most interactions simply follow the new cultural norms: ‘Alexa, set an alarm for 7am’. The norms are worth examining, but they do not reflect any personal animus on the part of the user. More positively, I know people use language models to support self-talk in much the way that children do with dolls and imaginary playmates: to try out bits of writing, riff on ideas, or tease something new out of a data set. I’m not a psychologist, but my hunch is this kind of interaction is easier when you have time and resources to play with. In a high pressure working or study situation, it may be harder to sustain this kind of playful, conversational engagement. (You’d expect me to say this, and I won’t disappoint: other techniques of self-talk are also available.)

In a recent class, my colleagues and I asked students to use an anonymised log-in to interact with ChatGPT. We reflected together on the emotional tone (as well as the informational content) of their prompts. Did they address the language model as a person? What kind of person? What kind of person did they find themselves speaking as? Did they notice any gender and cultural differences? Are these issues that educators should be interested in, I wonder?

Two roles that it is often suggested large language models can play in universities are ‘research assistants’ for scholars and ‘socratic tutors’ for students. Since we know that reframing and revaluing work is part of automation, we could ask how the work of real people in these roles might be affected. As well as being displaced or downgraded, might these roles also become associated with instant responsiveness and unfailing support (‘infinite love’)? Can would-be academics, overworked and precariously employed, ever live up to those expectations?

In thinking about this issue I found an opinion piece on ‘the Human ChatGPT: the use and abuse of research assistants’. It isn’t a particularly serious piece, but I think it raises some interesting questions. Similarly, the long and expensive history of ‘artificial tutoring machines’ has moved into a new phase, with students encouraged to elicit conversations with language models, general or specially trained on socratic conversations. I can find no research on how these automated chats might affect students’ relationships with tutors and graduate teaching assistants, but a great deal of commentary on how students value ChatGPT for ‘always being there’. There is nothing wrong with using interactive tools to support learning, writing and research, but it does not actually require a first-person natural language interface. It need not be called a ‘tutor’, ‘research assistant’ or ‘adviser’ to fulfil those functions.

We would be more honest about these systems’ limited capabilities if we agreed never to humanise them in this way. But, perhaps more importantly, if we remove the fetish we also remove one way that categories of work are open to being denigrated, even as real human beings continue to do them. In a mass university, students’ encounters with non-academic professionals, course administrators and casual instructors are significant to the humanity of their experience. Research assistants and teaching assistants are academics in training, and have it hard enough.

In the ‘imitation game’, Turing imagines a computer of the near future that he calls a ‘child machine’. It’s machine he can teach anything, a blank slate to be written on. The literature of theoretical AI - like contemporary AI product lines - is full of fake children, fake girlfriends, fake therapists and teachers, fake research assistants and personal administrators, fake friends. We know that many users imagine themselves in meaningful relationships with these agents. They may be a partial solution to loneliness - or a cheap alternative to a human service - or an opportunity for harmless play. But they are also a direct line to fetishising the objects of technology, giving the user an illusion of mastery while their behaviour is managed by the needs of the machine. Like all compulsions, they make us less able to cope with the accommodations and negotiations demanded by real relationships. Like all automation, they make us complicit in dehumanising some kinds of work. As Russ says, it’s time we put ourselves in recovery.

Things I read while writing this piece

The Conversation: Google’s powerful AI spotlights a human cognitive glitch (full article requires sign-in)

Lee (2018) Understanding perception of algorithmic decisions (open access)

Thomas et al. (2018) Algorithms as fetish (open access, may require institutional log-in)

Bonini et al. (2022) Mirror Neurons 30 years on: implications and applications (requires institutional log-in)

Laakasuo et al. (2021) Socio-cognitive biases in folk AI ethics and risk perception (open access, may require institutional log-in)

Meredith Whittaker interview (2023)What the president of Signal wishes you knew about AI panic (open access)

Miranda Marcus (2020) The god trick in data and design: how we’re reproducing colonial ideas in tech (open access)

Another powerful essay. Thank you, Helen.