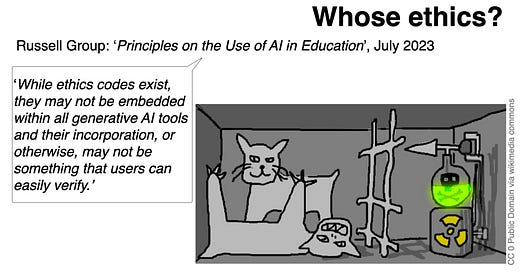

Whose ethics? Whose AI?

Following my keynote to the Association for Learning Technologies (ALT) winter summit on AI and ethics

Earlier this month I was honoured to speak at ALT’s winter summit on AI and Ethics. You can now download the (somewhat revised and tidied up) text of my talk, with slides alongside, and a better quality set of slides, minus the notes, if you prefer.

I recommend Lorna Campbell’s great summary of my piece, and other presentations from the event. While you’re on Lorna’s blog, it’s well worth reading her own take on generative AI ethics and indeed anything else she has written. Lorna is one of our most astute thinkers about open education and her values are always on point. I agree with her that:

These tools are out in the world now, they are in our education institutions, and they are being used by students in increasingly diverse and creative ways.

I’m also hopeful, like Lorna, that:

AI tools [can] provide a valuable starting point to open conversations about difficult ethical questions about knowledge, understanding and what it means to learn and be human

However, I am less convinced, overall, that they can ‘mitigate the impact of systemic inequities’. This is an issue that will require a lot of research, at different levels of practice and impact, and certainly deserves a separate post.

Meanwhile, there was time for a couple of questions on the day but not for all the interesting thoughts that people wanted to share. So I offered to follow up with some more detailed responses, hopefully continuing the conversation.

Question: How realistic is it for (European) academia to develop an open ecosystem [for generative AI]?

This was a response to my closing remarks about the need for higher education sectors to develop - or at least contribute to the development of - models that are more fit for purpose for teaching, learning and research than those on offer from the big tech corporations. I said:

We need to be creating an ecosystem in which ethical choices are actually available... The new EU regulations on AI are actually rather good at defining different kinds of ethical actors in the AI space… The responsibility for providing an ethical environment in which systems are deployed lies mainly with the organisations providing the systems, in our case with universities and colleges, and their regulatory bodies.

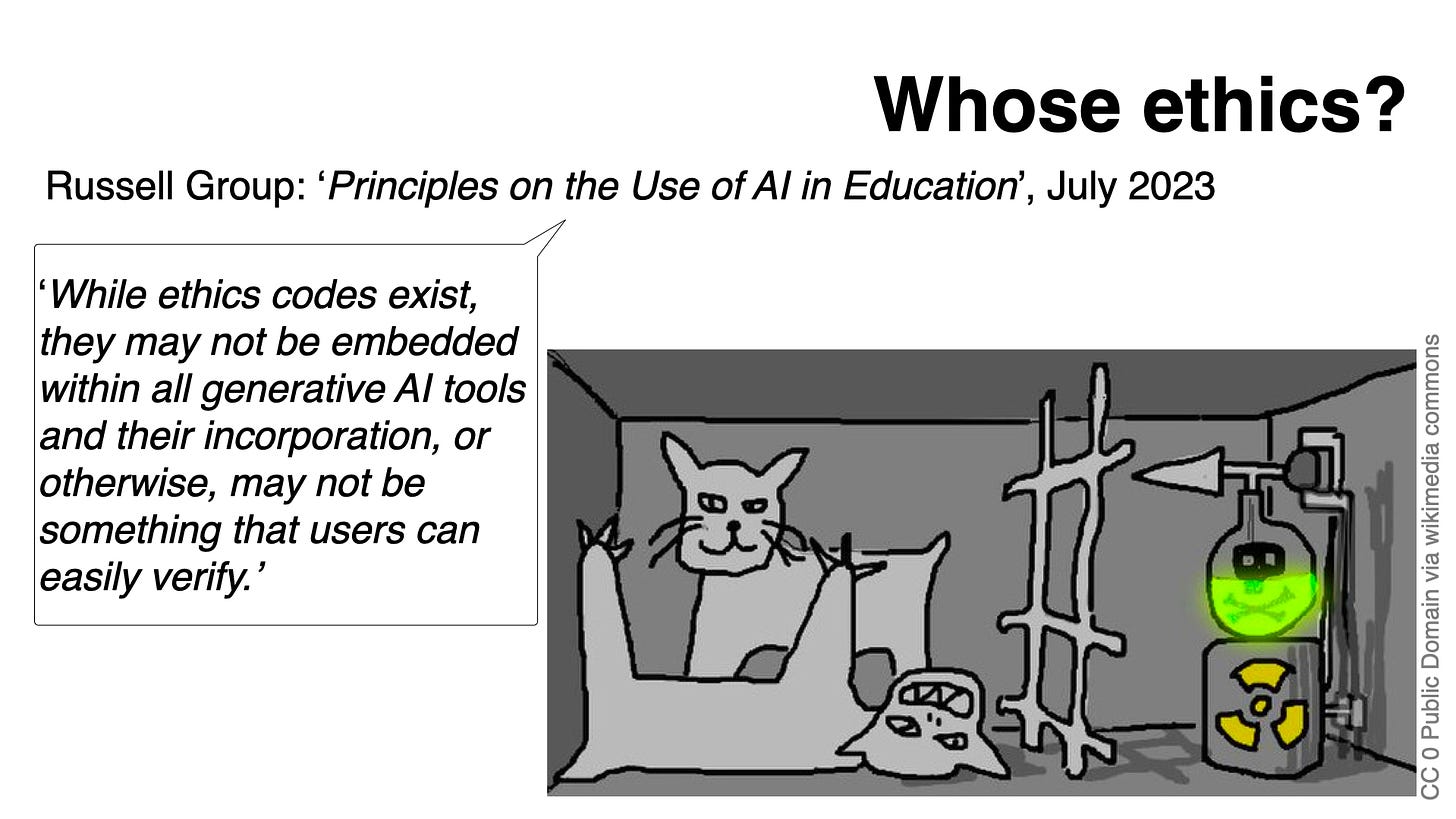

The regulations classify all AI systems in education as high risk, because of their lifelong implications for learners. And as such, they require all of these things from providers:

Adequate risk assessment and mitigation

High quality datasets to minimise risks and biases

Full record to ensure traceability and accountability

Appropriate human oversight

Robustness, security, accuracy

(all paraphrasing from the EU Artificial Intelligence Act, text of December 2023)

Now, do any of the models we are using in universities and colleges currently meet these requirements? And if not, how do we get there? I don’t see how we can do that as a sector, without building and maintaining our own models, or at least being part of an open development environment in which we can verify that all these requirements are being met. Very large, very rich companies are doing this already. I have no doubt rich universities and research institutes are close behind. But unless we do this in collaboration, it will become a major new source of inequity across the sector. I also think the big corporate players will simply swallow up organisational projects, in the guise of partnerships perhaps, and with what consequences for their knowledge assets?

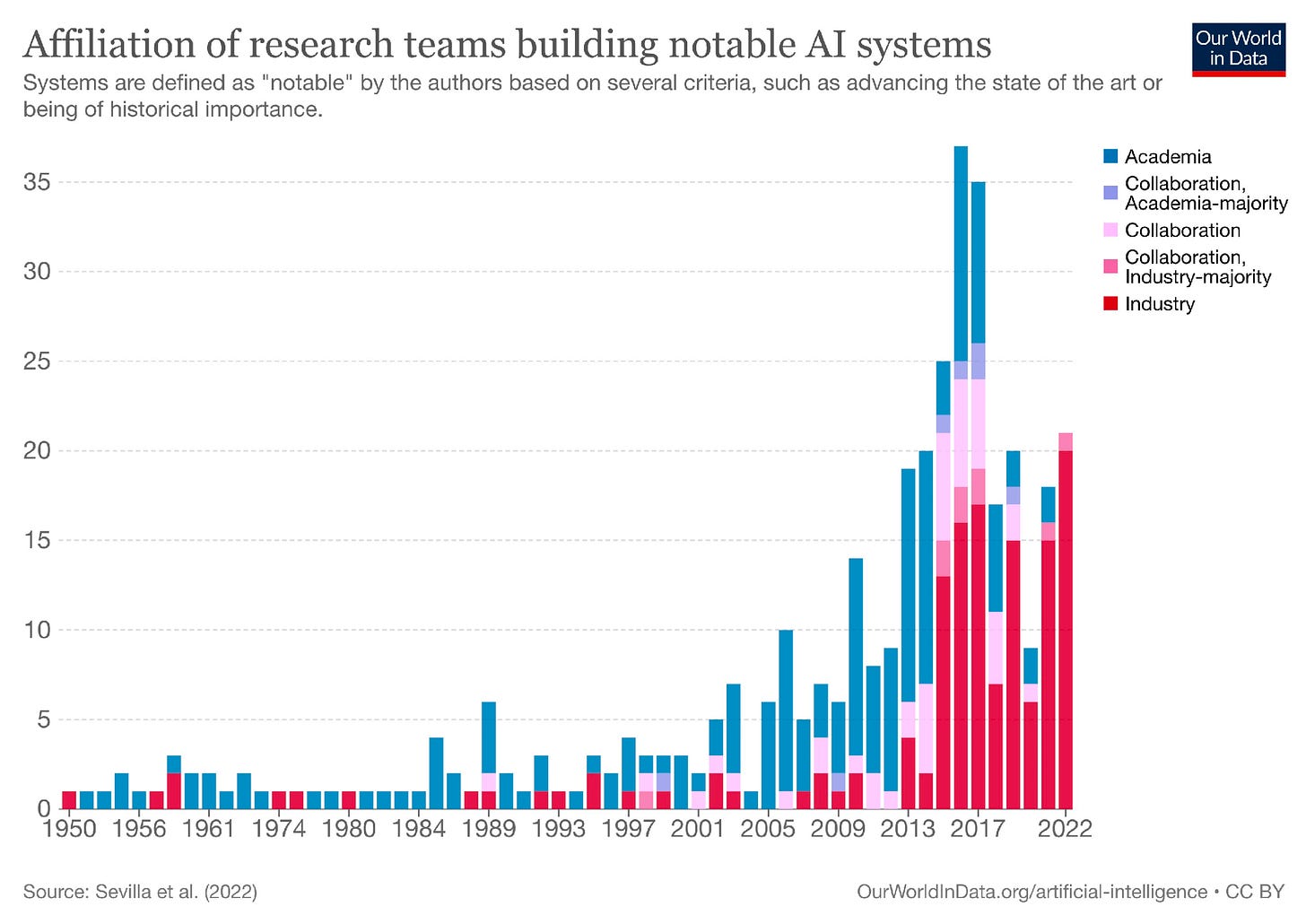

Even collaboratively, this will be a huge challenge. This chart from my talk shows the huge brain drain there has been from academic AI to the commercial sector.

There may be no way to avoid some relationship with the big commercial models. But by having a collective voice, the sector can negotiate that relationship - as it does with other platforms, subscriptions, and digital resources (thanks, in the UK, to bodies like Jisc/HESA).

Collectively, universities and colleges are key actors. Perhaps uniquely as a sector we have the know-how. We have a very particular stake in knowledge, knowledge production, and values around knowledge. And we do have expertise in building open knowledge projects. We have contributed extensively to open standards since the birth of the internet. Without the support of the academic sector, there would be very few open source developers, open science and research scholars, open access publications or open education practitioners.

So, in response to this question, I agree that it is too much to ask the academic community to do all the work of developing an open ecosystem. But that is not required. Open models are now being built that can run on a laptop. Open source tools, APIs and other elements of an open ecosystem are developing rapidly. What is needed is for the sector to decide what kind of ecosystem it wants – a commons of shared tools, data and expertise, with an explicit public mission, or a landscape of defended ivory towers, each highly vulnerable. If we go down the open route there is, I think, obvious scope to work with other sectors such as heritage that hold important repositories of knowledge. How can language modelling allow for wider access to this knowledge, and how can it actually enhance that knowledge, especially for teachers, learners and researchers? We will also have to deal with three key ethical challenges, and I think we can only do this as a whole sector: the human and computing power required; the future of creative commons licensing in relation to synthetic models; and the equitable, open, unbiased and transparent use of data.

Some of these challenges are explored in a recent paper by Zuzanna Warso and Paul Keller, part of the openfuture.eu team, who conclude that:

openness alone will not democratize AI. However, it is clear to us that any alternative to current Big Tech-driven AI must be, among other things, open.

It’s interesting that the question recognises the EU as a key player. The EU is certainly ahead of the game, not only in regulation but in thinking about what a shared, open, public infrastructure for AI would look like. Another recent post from the openfuture.eu team lays out principles that I think should obviously apply to the academic sector: protect the rights of workers and creative producers; develop public infrastructure and a public data commons; resist partnership with private big tech corporations. The EU is making significant investments in joined-up development, for example as part of the Open Science cloud, that UK universities could be part of, or could at least be matching.

And then, as if by magic…

Simon Buckingham-Shum at the Open University posted a highly relevant question on LinkedIn:

Simon reiterates the point (from Meredith Whittaker’s paper on the ‘Steep Cost of Capture’) that universities lack the resources to build their own infrastructure. My point is rather that the sector could contribute to public infrastructure projects, alongside other sectors such as culture and heritage, as in these examples from Sweden, Finland and the Netherlands. But I don’t underestimate (or fully understand) the technical challenges: I’m not even sure such capability would be truly ‘sovereign’. I just think that efforts to build openly, at scale, would shift the balance between private and public interests, and would make some of the ethical issues more visible, even if in the end it could not solve them all.

Question: You spoke about things we can do as a sector that would require quite a lot of coordination and collaboration, which I would agree with. What can we do as individual educators?

So, a big part of my talk was trying to challenge the idea that individuals can act ethically in a context where there is no supportive infrastructure for making informed ethical choices or for seeing them through in practice. And that is the situation I think we find in universities and colleges just now. But of course we still have to relate to students, colleagues, to make choices about how we do the work of teaching and research. I don’t want to pretend to have the kind of practical experience that others have been developing this past year. I follow Anna Mills, for example, who I think is doing amazing work, Chrissie Nerantzi and her colleagues. Katie Conrad, almost anything that comes out of the Critical AI blog at Rutgers.

I would tentatively put forward these thoughts, with the proviso that they are not based on any evaluation with students, and only as a kind of counter-weight to some of the ideas that I see being promoted, with little or no research to back them up.

I think synthetic models can be useful as translators, or transposers, where you upload a piece of text (or code) and rephrase it, expand it, contract it, elicit comments, try different ways of styling it and recognise what else it might be saying. Anything that helps students to think about their work more flexibly, more playfully, can be a good thing. However, there is always the risk that text will be re-used in model training and may find its way into the public domain, so I’d always suggest using an enterprise version or a closed model if that is available.

But we don’t need large language models to get students exploring their own and other people’s writing in creative ways. Many tools developed in the digital humanities can do this. Any good reference or notes management app can do this for materials students have collected and produced themselves. Annotation environments, text density maps, mindmapping…? ChatGPT’s capabilities are fun but really rather limited when you think of how many ways students can experience text.

I feel we should probably avoid ‘prompt engineering’ as a term, and definitely stop selling it as an important skill. I think it will be about as relevant to graduate employment as writing html code, and for the same reasons. Alongside all the ‘100 best GPT prompts’ you can cut and paste from the internet, the ability to call up ChatGPT (or another model) is already being integrated into search engines and browser extensions and thousands of intermediary apps. They offer drop-down lists or push-button choices, or helpfully assume what it is you need to know. What I think we probably should do, working with our colleagues in libraries and study skills centres, is to update our support for search skills. Help students to understand what the algorithms are hiding as well as what they are revealing, how to search when you know what you are looking for as well as when you don’t, the business models as well as the algorithms of search, and how search online is being systematically degraded both by commercial interests and by these new synthetic capabilities. We may conclude that students are better off learning how to use the walled gardens of content that academic libraries and subscriptions provide – which ties in with my arguments about building our own ecosystems. That will also equip them for search ‘in the wild’.

In this brief window of time when people are still crafting their own input, I do find it interesting that ‘getting the AI to say something useful’ seems to have unleashed so much creativity in the design of prompts for writing. But I wonder whether it might be just as helpful to offer these prompts to students to try out for themselves, as a way of closing on what it is they want to say, or opening out on what it is possible to say. Or better still if they were designed by students and offered to each other. In live writing sessions where they can experiment, give and receive meaningful feedback, and learn from other people who are learning the relationship between thinking, writing, and responding.

Of course I don’t think we should ban the private use of chatbots or make unreasonable demands on students to account for their use. That seems to me entirely counter productive. I just think we should stop telling students that their future depends on becoming proficient in these technologies. Graduate recruiters, as I said in my talk, are finding ways to exclude generative tools from the recruitment process. If these companies are using generative tools for knowledge management, or specific productivity gains, they will train recruits on their own proprietary systems. Meanwhile they want people who can think, write, speak and innovate for themselves.

Question: Is it ethical to require students to use Gen AI for assignments?

This is a good follow-on from the previous question. I think it depends on the task. If the task is to develop a writing process, to try different synthetic tools and functions, to become aware of what is gained and lost in using them, then use is part of the learning. And if the task is to ask critical questions, well, use can reveal some of the model’s underlying assumptions and biases. So long as it comes in the context of other input such as critical questioning. But in most situations, as Katie Conrad says in her wonderful Blueprint for an AI bill of rights in education, I think students should be offered alternatives. I have talked about ‘spaces of principled refusal’. That is something I think students generally understand, from other contexts. But then it’s important to think about what we put into those spaces that can give students more confidence in their own voice and process. Not just ‘write an essay’ but a range of prompts and challenges, in different media, at different intensities and spans of time.

One thing I like about the uses of generative AI that I see being developed is they are often playful. I used to teach creative writing and I was always making little games for my students. I would design sequential prompts for writing tasks that I called ‘poetry machines’. I took a lot of ideas from other writing teachers, creative and academic. There is a wealth of material for teaching writing and self-expression that most students never get exposed to, that most academics don’t have time to explore. It’s a good time to draw on, share and enrich those resources.

Question: Excellent presentation, my question is : what is your thought on using of AI in the assignment submission ? and how we can work closely to detect?

My thought is that students are doing this, and will go on doing it, and we don’t have any reliable way of detecting it. And a focus on detection has two very negative consequences. One, it encourages students to invest in making their writing ‘AI detection proof’, whether that’s investing time that would be better spent on writing, or spending money on paid-for services. And neither investment is going to support their learning. So then, two, what should be a supportive relationship around setting tasks and sharing feedback becomes an arms race between rival technologies. It undermines trust. We are lying to students if we tell them we can reliably detect the use of AI, and we are asking them to lie to us if we tell them not to use it. So alongside instrumentalism, which is there already, you invite cynicism. Despair, even.

A better approach, as many commentators have said, is to design assignments that make the use of generative tools less compelling. I’ve produced my own list of what I call ‘accountable assignments’ that focus on developing personal interests and positions and purposes. I’m also interested in assignments that emphasise time on task. That might mean writing or presenting live (not under exam conditions). It might mean producing assignments over several iterations, or punctuating the process with new prompts, review points, and other kinds of ‘checking in’. Students are invited to slow down and notice how time is part of the process, not something to be avoided. Taking time can improve their thinking in ways that speed and hyper-productivity might not.

An approach I took this year, like many of us, was to have an open conversation with students about writing tools and how they influence practice, with their own writing on the table but in a low-stakes setting. I used examples to show how writing can be made poorer through bad choices, as well as more convincing through good ones (though these, too, take time!). If I notice an unskilled use of generated text, I might say something like: ‘Can you think about how you produced this sentence/paragraph/piece of writing? Could you produce it differently, in a way that convinces me that you really understand what you are writing about?’ Hopefully, that invites them to focus on their process and to ask for help if they need it.

There is less time to get familiar with individual students’ work when you are teaching large cohorts of undergraduates, I get that. But there is still time to have conversations about writing practice. I know universities, and departments, and ALT colleagues who are doing really brave work with students, sharing doubts and fears and questions, as well as positive ideas. If students are instrumental, let’s bring that into the conversation. ‘Everyone else is using this: I can’t afford not to’. We can all relate to that feeling. So what exactly is the fear? If students are cynical, how can we lean in to that? What makes their learning feel more purposeful and relevant? And if they have fundamental doubts about the value of studying at all, when ‘AI is taking all the jobs’ or ‘AI can do this better than I can’, at what level should we respond? There is always the opportunity to expand the context and talk about what agency students have to shape their own futures.

Of course if you are using synthetic media with students and having positive results, you should share that, absolutely. I would insist, though, that we share with students what we have found to work with students, in their context, which is primarily for learning. We should not assume our own productivity gains will translate. Anyone who has an established writing or coding or illustration or music-making practice can find ways to integrate synthetic media, if they are motivated to. Anyone who knows roughly what response they are looking for can write and rewrite prompts until they find something that fits. Learners have neither an established practice, nor a clear conceptual framework to start from. So they are unlikely to get the same results. And if we do help fast-track them to the results, we need to be sure we are not setting back the work of developing the practices and the conceptual frameworks they need. For synthetic tools to be part of a repertoire, you need the rest of the repertoire.

We use what students produce as signs and proxies for learning, and if they stop being reliable signs, we probably need to find different ones. That’s on us. It does not mean throwing out the whole curriculum. It might mean focusing on different assessment formats such as vivas and presentations and personal projects. It might mean investing more in those tasks and conversations that excite students, and challenge their development. It might be as simple as rebalancing assessment rubrics. I strongly resist the narrative that ‘everything must change’. And I even more strongly resist the narrative that students’ ‘academic integrity’ should bear all the ethical burden here.

If Lorna is right and there is a door open here, on questions about knowledge, understanding and what it means to learn and be human, we can step up to the challenge by asking those questions alongside students. Not by presenting them with tidy answers, and certainly not by looking to synthetic models of text for ethical insights. How they are embedded into learning, how they facilitate or fail our values of equity and access to knowledge, is not up to the giants of tech, or the hype merchants. It is up to all of us. But we need our sector, collectively, to provide us with the ethical leadership and the practical means to respond.